Serving Two Needs

Governor Sprague helped broker a deal that brought a sizable number of farm laborers of Japanese descent to the fields of Malheur County. (Image courtesy Library of Congress)

Governor Sprague helped broker a deal that brought a sizable number of farm laborers of Japanese descent to the fields of Malheur County. (Image courtesy Library of Congress)

The festering resentment and rioting that occurred at Tule Lake and Manzanar served to underscore the ongoing critical importance of employing as many Japanese American internees as possible. At the same time, eastern Oregon farmers desperately needed help tending and harvesting the sugar beet crop. Matching the two needs would prove to be more challenging than imagined.

Acute Labor Shortages

Pearl Harbor accelerated an earlier trend that saw millions of young men moving from America's farms and into military service and defense production jobs. This left agricultural producers scrambling for help in the fields, especially during harvest time. Officials made efforts to fill the gaps, such as postponing the beginning of school so that local students could assist in the harvest; importing Mexican "braceros" laborers; and encouraging urban dwellers to help with the harvest. One effort sought to bring thousands of Japanese American internees to the sugar beet fields of eastern Oregon.

Well before precise plans developed and Oregon's 4,000 Japanese Americans were ordered to the assembly center, state officials were making a pitch to the War Relocation Authority to put them to work on public works projects or in the farm fields of eastern Oregon. Governor Sprague's secretary, George Aiken, presented the plan to the head of the WRA and governors and representatives of ten western states at an early April 1942 conference in Salt Lake City. The "Oregon Plan" called for moving internees to abandoned Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps in Malheur, Harney and Crook Counties. There, the Japanese Americans would provide year-round work on public land and transportation projects and supplement farm labor needs in the beet and vegetable fields of Malheur County. The plan called for the laborers to be under federal supervision and paid prevailing wages. Moreover, the workers would be under guard at all times and would be "returned to the community from which they came at the close of the war." During the meetings, Oregon was the only state to present a "definite and concrete program for evacuation." While conference attendees responded favorably to the plan, ultimately the WRA rejected it and Oregon officials moved forward with a less ambitious farm labor proposal.

Footnote

1Sugar Beet Harvest Seen as Critical

Japanese American laborers work in the sugar beet fields near Nyssa in 1942. Sugar was a highly valued commodity during the war. (Library of Congress, image no. fsa 8c25290)

Japanese American laborers work in the sugar beet fields near Nyssa in 1942. Sugar was a highly valued commodity during the war. (Library of Congress, image no. fsa 8c25290)

National needs drove the sugar beet problem in Malheur County. With the ramp up to war, the federal government felt pressure to increase sugar production, both for use in explosives (using industrial alcohol processed from sugar) and for beverage alcohol. Seeing an opportunity, eastern Oregon's major producer, Amalgamated Sugar Company, talked Malheur County farmers into converting other crops to sugar beets. With the conversion beginning in March 1942, the only thing missing was a labor force to thin and harvest the crop. Soon farmers were sending desperate pleas to the president and the governor in a frantic effort to move Japanese American laborers to the fields.

Before the pleas could be answered, federal authorities demanded that state and local governments give several assurances: that prevailing wages would be paid; that imported labor would not compete with available local labor; that the employer would provide housing and transportation; and that the labor be entirely voluntary. But most importantly, the state and county were to guard the workers, largely from any locals who may have been harboring anti-Japanese sentiments. Essentially, federal officials wanted guarantees that going along with this would not create headaches for them.

Footnote

2 Malheur County officials were anxious to move forward: "The farmers in this area have approached us repeatedly in the past few weeks to try to get Japs in here because other labor was not available. Many of the farmers are faced with the problem of plowing their beets under if labor can not be had within the next few days." They further assured that "we are confident that our local constituted authority can maintain law and order in case the Japanese are brought in here from Portland."

Footnote

3 Finally, federal officials agreed to the plan:

Governor Charles A. Sprague

May 14, 1942

Dear Governor:

At the direction of the President, I gave your message to Mr. Eisenhower [WRA director]. He tells me that, in the understanding that you have guaranteed to maintain law and order in any portion of Oregon to which evacuees might go, the War Relocation Authority today authorized their organization in California to permit the U.S. Employment Service voluntarily to recruit among the evacuees, the companies to pay transportation and prevailing wages.

Grace G. Tully

Acting Secretary to the PresidentFootnote

4

The recruitment of workers disappointed the governor and farmers. Japanese Americans, fresh from abandoning their lives to move to the Portland Assembly Center, were skeptical of the hard sell technique of recruiters. And they were downright alarmed at the rhetoric that had come from some of the Caucasian zealots in Malheur County. A representative of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) conveyed these concerns to Governor Sprague: "I believe it is too much to expect evacuees to jump at the opportunity of working in the sugar beet fields, when you consider that the very area from which the request comes now, only a few weeks ago made the statement to your office that they would take vigilante action if the Japanese were allowed to go into Malheur County. Reassurance is not sufficient, there must be absolute guarantee of the provisions of the agreement with the employers. I have the utmost confidence in the people of Oregon on this subject matter."

JACL Letter from Hito OkadaFootnote

5

JACL Letter from Hito OkadaFootnote

5New Routines Set

Japanese Americans at the Farm Security Administration camp at Nyssa share a meal. Many families were reluctant to leave internment camps to work in the sugar beet fields, partially based on concerns about anti-Japanese sentiments in the area. (Library of Congress, image no. fsa 8c25222)

Japanese Americans at the Farm Security Administration camp at Nyssa share a meal. Many families were reluctant to leave internment camps to work in the sugar beet fields, partially based on concerns about anti-Japanese sentiments in the area. (Library of Congress, image no. fsa 8c25222) Eventually, the spring crisis was averted by the actions of 43 young Nisei who went to Malheur County to thin the sugar beet crop. They agreed to telephone and wire other evacuees and encourage them to help. The effort worked and by June 11 farmers reached the target of 400 workers. While some of the crop had been plowed under, the majority was saved, prompting the president of the Amalgamated Sugar Company to offer his "sincere appreciation" to Governor Sprague: "There was, of course, some loss of sugar beet acreage as a result of the labor shortage. However, that acreage represents only a fraction of what might have been lost had we not enjoyed such splendid cooperation from your office. The successful employment of Japanese as farm workers in Malheur County has not only benefited Oregon but has served to demonstrate to areas in other states a solution to a very serious problem."

Footnote

6

During the summer local farmers put the new labor force to work on other jobs. Most of the 400 Japanese Americans who came to help with beet thinning stayed through the summer. During the height of the summer, work decreased in the sugar beet fields and the laborers went "into other lines of agricultural work such as haying, threshing grain, potatos [sic], celery, onions, tractor driving, irrigation, and most any other kind of agricultural work." Six workers were busy removing moss from irrigation ditches maintained by the Warm Springs Irrigation District. Moreover, the worker program had attracted the interest of farmers in adjoining counties of Idaho and some of the laborers were crossing the Snake River to work.

Footnote

7

Japanese American farm workers prepare to leave the Farm Security Administration camp near Nyssa for work in the fields. Local farmers sent trucks to the camp to pick them up. (Library of Congress, image no.fsa 8a31229)

Japanese American farm workers prepare to leave the Farm Security Administration camp near Nyssa for work in the fields. Local farmers sent trucks to the camp to pick them up. (Library of Congress, image no.fsa 8a31229) Regulations governed the Japanese American workers, about 235 of whom lived at the former Nyssa Civilian Conservation Corps camp with approximately 150 more workers living on individual farms scattered throughout the expansive county. Most of the rules were designed to minimize conflict with local detractors, especially drunk ones. Therefore, the Japanese American workers were subject to curfew from 8 p.m. to 6 a.m. five nights a week, of which Saturday had to be one. Two nights a week, the workers could be out until 11 p.m. Any worker out after curfew needed to have a special permit. Further regulations limited visitors at the camp and prohibited pleasure driving by Japanese American workers who owned cars.

Curfew Regulation Meeting NotesFootnote

8

Curfew Regulation Meeting NotesFootnote

8 Local Impressions of Workers Vary

Longtime county residents and observers offered various impressions of their new neighbors. R.G. Larson, who ran the district office in Nyssa for the Amalgamated Sugar Company, reported in August that "thus far there has not been a single unpleasant incident arise in connection with the Japanese program. They are good spenders and behave themselves when in town; consequently, the merchants are satisfied. They are good field workers which satisfies the farmers."

Letter from R.G. LarsonFootnote

9

Letter from R.G. LarsonFootnote

9

By November, Joe Dyer, manager of the United States National Bank branch in Ontario, reported that "Charles Garrison told me a few days ago that his entire beet crop has been delivered and that he had very little or no trouble with any of his help." O.F. Wilkins of Oregon Slope also "stated that he had an exceptionally good group of Japanese beet toppers...." But other residents weren't shy about registering negative experiences. Bill De Grofft of Nyssa claimed that he couldn't get a "worthwhile" Japanese crew: "Some of them would come and work for a day or two and then fail to show up the following morning." De Grofft added that "they were very slow and apparently did not care whether they worked or not."

Footnote

10Social and Cultural Friction

Social and cultural differences also led to friction as Joe Dyer observed in a letter:

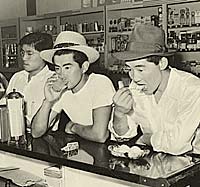

Young Japanese American workers spend time at the fountain of a Nyssa drug store. (Library of Congress, image no. fsa 8c25281) George K. Aiken, Executive Secretary to the Governor

Young Japanese American workers spend time at the fountain of a Nyssa drug store. (Library of Congress, image no. fsa 8c25281) George K. Aiken, Executive Secretary to the Governor

November 6, 1942

Dear George:

...One of the other things which irks so many people in this area with the Japanese is that they come to town in large groups and when they go into various stores to make purchases, they practically take the place over, which is offensive to the white people. I have seen instances in Taylor's Coffee Shop after a picture shop [sic-motion picture show] in the evening where the fountain and every booth was filled with young Japs. Harry Salisbury at the Moore Hotel had a little trouble with them congregating in the lobby and found it necessary to instruct them to move on.

Another thing which causes a considerable amount of comment is the fact that so many young able bodied Japanese boys are seen on our streets on the forenoon and afternoons of working days when their services are so badly needed in the fields. Upon making further investigation, I learned that quite a number of these Japs are not experienced farmers, having come in here from the Seattle District where they operated as merchants and shop owners. Consequently, when they are put in the fields to harvest our sugar beets, they are no better than the average white office worker.

Joe F. Dyer, Manager

United States National Bank, Ontario BranchFootnote

11

By November 1942 only one serious "flare up" had occurred in Malheur County, this one centered in the tiny hamlet of Harper. According to the report:

"...one of the natives after imbibing too freely took it upon his [sic] self to get his Jap. Apparently the Jap was beat up considerably and the Harper boy was fined $25.00 for disturbing the peace, which I understand he readily paid."Footnote

12

Officials Aim to Move More From Camps to Work

Federal regulations promulgated in September 1942 sought to move more internees out of internment camps and into jobs. According to one report, "the War Relocation Authority is now working toward a steady depopulation of the [relocation] centers by urging all able bodied residents with good records of behavior to reenter private employment in agriculture or industry." By 1943 significant numbers of Japanese Americans were taking advantage of the indefinite leave program to move on to jobs and college classrooms located outside of the exclusion zone.

The War Relocation Authority set up four major requirements to be satisfied by applicants:

Japanese Americans farm workers congregate in front of the Nyssa Theater. (Library of Congress, image no. fsa 8c25304)

Japanese Americans farm workers congregate in front of the Nyssa Theater. (Library of Congress, image no. fsa 8c25304)

- Officials conducted a careful check of the internee's behavior record at the relocation center. In questionable cases, FBI and other investigation information was requested. Any evidence of a security risk was grounds for denial.

- Officials or citizens from the receiving community had to give "reasonable assurances" that local sentiments related to Japanese Americans were positive. If responses proved hostile, the internee would be advised to revise plans.

- Internee applicants for leave needed to show a definite place to go and some means of support.

- If approved, the internee would be required to inform the WRA of any job or address change.Footnote

13

The WRA sent field employees to set up shop in key cities throughout the interior of the country to help match internee leave applicants with employers offering jobs. Overall, thousands of internees found new temporary homes away from the internment camps. By 1945 most internees were permitted, and later compelled, to leave the camps.

Notes