Section map (enlarge image).

Section map (enlarge image).

From the winding curves of RAINIER HILL (671 alt.) there is a fine view of Longview, Washington, and the narrow roadway of the bridge spanning the river, hundreds of feet below. The summit is reached at 50.6 m.

Descending, the highway crosses ubiquitous BEAVER CREEK, 51.4 m. Within the next 15 miles westward the road spans the stream a dozen times. The country now presents wide expanses of logged off land.

At 61.7 m. is a junction with a gravel road.

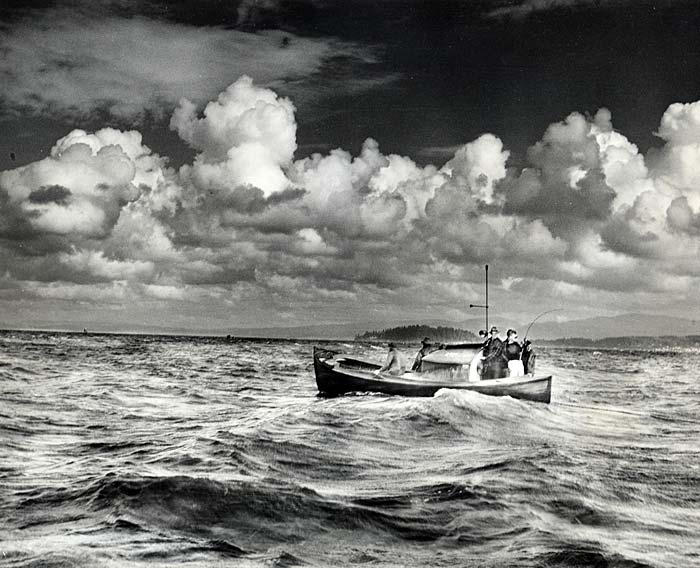

Fishing boats take part in the Astoria Salmon Derby (933). Enlarge image.

Fishing boats take part in the Astoria Salmon Derby (933). Enlarge image.

Right on this road to QUINCY, 1 m. (18 alt., 503 pop.), center of a drained and diked area of the Columbia River lowlands; L. here 3 m. on a dirt road to OAK POINT. The Winship brothers of Boston attempted to establish a trading post and settlement here known as Fanny's Bottom. On May 26, 1810, while Astor was still maturing his plans for the Pacific Fur Company, Captain Nathan Winship arrived in the Columbia River with the ship Albatross. He began construction of a two story log fort and planted a garden. However, the attempt was abortive. Robert Stuart, of the Astorians, wrote in his diary, July 1, 1812: "About 2 hours before sunset we reached the establishment made by Captain Winship of Boston in the spring of 1810 It is situated on a beautiful high bank on the South side & enchantingly diversified with white oaks, Ash and Cottonwood and Alder but of rather a diminutive size here he intended leaving a Mr. Washington with a party of men, but whether with the view of making a permanent settlement or merely for trading with the Indians until his return from the coast, the natives were unable to tell, the water however rose so high as to inundate a house he had already constructed, when a dispute arose between him and the Hellwits, by his putting several of them in Irons on the supposition that they were of the Chee-hee lash nation, who had some time previous cut off a Schooner belonging to the Russian establishment at New Archangel, by the Governor of which place he was employed to secure any of the Banditti who perpetrated this horrid act The Hellwits made formidable preparations by engaging auxiliaries &c. for the release of their relations by force, which coming to the Captain's knowledge, as well as the error he had committed, the Captives were released, every person embarked, and left the Columbia without loss of time "

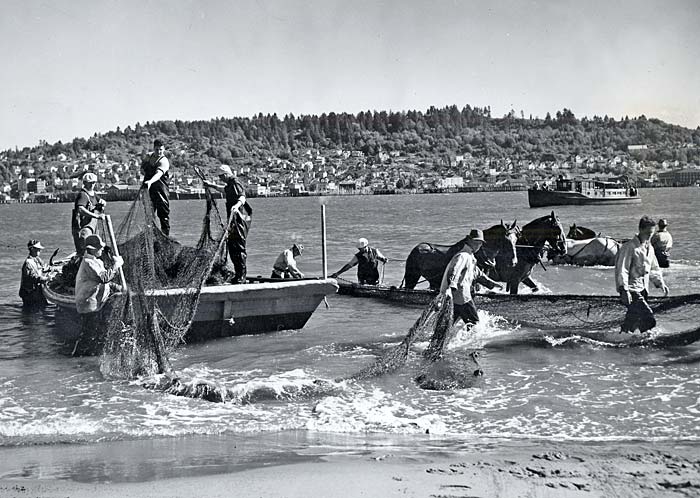

Horse sein fishing on the Columbia River (1297). Enlarge image.

Horse sein fishing on the Columbia River (1297). Enlarge image.

CLATSKANIE (cor. Ind., Tlatskanie), 64.8 m. (16 alt., 739 pop.), bears the name of a small tribe of Indians that formerly inhabited the region. The town is on the Clatskanie River near its confluence with the Columbia and is surrounded by rich bottom lands devoted to dairy and raising vegetables for canning. In 1852 E. G. Bryant took up the land on which a settlement grew, named Bryantsville. In 1870 the name of the town was changed to Clatskanie and it was incorporated as a city in 1891. State Fisheries Station No. 5, for restocking the river with fingerling salmon, is at this point.

At 65.2 m. is the junction with State 47.

Left on State 47 over a mountainous grade into the Nehalem Valley and across a second ridge into the Tualatin Valley to FOREST GROVE and a junction with State 8 at 56.1 m.

WESTPORT, 74.5 m. (32 alt., 450 pop.), is one of many lumber and fishing towns scattered along the Columbia.

The highway ascends the Coast Range in a series of hairpin turns to CLATSOP CREST, 79.7 m., overlooking the Columbia River and the country beyond. In the immediate foreground is long, flat PUGET ISLAND, where grain fields and fallow lands weave patterns of green and gray, and sluggish streams form silvery canals. Although the island is close to the Oregon shore, it lies within the State of Washington. It was discovered in 1792 by Lieut. Broughton of the British Navy, who named it for Lieut. Peter Puget.

US 30 twists down to HUNT CREEK, 80.7 m., then climbs a spur from which a desolate waste of logged over land extends in all directions. A high, sharply etched mountain (L), with sides bare of vegetation, shows the results of unrestricted timber cutting.

At 92.5 m. is a junction with an improved road.

Dairy cattle along the lower Columbia River Highway (896). Enlarge image.

Dairy cattle along the lower Columbia River Highway (896). Enlarge image.

Right here to SVENSON, 0.7 m. (10 alt., 100 pop.), less a town than a series of fishing wharves, extending into the Columbia River, which broadens to a width of five miles. Tied up at the docks are many fishing crafts. These small boats, their engines hooded for protection from spray and weather, ride restlessly in the tide's movement. Net drying racks stretch at length over the salt soaked planking, where fishermen mend linen nets between catches.

It is from these docks, and the many that closely line the river's south shore from this point to Astoria, a distance of eight miles, that a large portion of the salmon fishing fleet puts out.

The principal method of taking fish in the Columbia is by gill netting. The gill netter works with a power boat and a net from 1,200 to 1,500 feet long. On one edge of the net are floats to hold it up and on the other edge weights to hold it down and vertical in the water. Fish swarming upstream strike the net and become entangled in the meshes, held by their gills. The gill net fishermen usually operate at night; at such times the river presents a fascinating spectacle, dotted with lights as the boats drift with the current.

Seining operations are employed on sand shoals, some of them far out in the wide Columbia estuary. One end of the seine is held on shore while the other end is taken out into the river by a power boat, swung around on a circular course and brought back to shore. As the loaded net comes in, teams of horses haul it into the shallows, where the catch is gaffed into boats. Seining crews and horses live in houses and barns on the seining grounds. Fishing crews often work in water to their shoulders.

Trolling boats are larger than gill netters and cross the Columbia bar to ply the ocean waters in search for schools of salmon, and for sturgeon, which are taken by hook and line. They carry ice to preserve their cargo, as they are sometimes out for several days.

The Astoria Salmon Derby weigh station (3864). Enlarge image.

The Astoria Salmon Derby weigh station (3864). Enlarge image.

Mysterious are the life and habits of the salmon which provide the lower Columbia with perhaps its main industry. Spawned in the upper reaches of the river and its tributaries, the young fish go to sea and disappear, returning four years later to reproduce and die where they were spawned. Each May large runs of salmon come to the river and fight their way against the current; each autumn the young horde descends. Full grown King Chinook salmon weigh as much as 75 pounds each.

Until 1866, salmon were sold fresh or pickled whole in barrels for shipping. In that year the tin container came into use. By 1874, the packing industry had become an extensive commercial enterprise. Artificial propagation, to prevent fishing out of the stream, began in 1887. Today, about 3,500 fishermen are engaged in various methods of taking fish in the Columbia River district, and about 1,800 boats of various sizes and types are used. It has been estimated as many as 20,000 persons now depend upon the industry for a living. The value of the annual production , most of which is canned at the processing plants at Astoria and elsewhere on either side of the river, is estimated at ten million dollars.

US 30 crosses the little JOHN DAY RIVER, 97.9 m., another stream named for the unfortunate Astorian of whom Robert Stuart says as he camped a few miles up the Columbia: "evident symptoms of mental derangement made their appearance in John Day one of my Hunters who for a day or two previous seemed as if restless and unwell but now uttered the most incoherent absurd and unconnected sentences ... it was the opinion of all the Gentlemen that it would be highly imprudent to suffer him to proceed any farther for in a moment when not sufficiently watched he might embroil us with the natives, who on all occasions he reviled by the appellations Rascal, Robber &c &c &c "

Nearing the western sea they had been sent to find, Lewis and Clark recorded enthusiastically, on Nov. 7, 1805, "Ocian in view. O the joy." On the following day he wrote: "Some rain all day at intervals, we are all wet and disagreeable, as we have been for several days past, and our present Situation a verry disagreeable one in as much, as we have not leavel land Sufficient for an encampment and for our baggage to lie cleare of the tide, the High hills jutting in so close and steep that we cannot retreat back, and the water too salt to be used, added to this the waves are increasing to Such a hight that we cannot move from this place, in this Situation we are compelled to form our camp between the Hits of the Ebb and flood tides, and rase our baggage on logs."

Sailboat races near Astoria (1580). Enlarge image.

Sailboat races near Astoria (1580). Enlarge image.

On the 9th he wrote: "our camp entirely under water dureing the hight of the tide, every man as wet as water could make them all the last night and to day all day as the rain continued all the day, at 4 oClock PM the wind shifted about to the S.W. and blew with great violence immediately from the Ocean for about two hours, notwithstanding the disagreeable Situation of our party all wet and cold (and one which they have experienced for Several days past) they are chearfull and anxious to See further into the Ocian. The water of the river being too Salt to use we are obliged to make use of rain water. Some of the party not accustomed to Salt water has made too free use of it on them it acts as a pergitive. At this dismal point we must Spend another night as the wind & waves are too high to preceed."

At 100.7 m. is TONGUE POINT STATE PARK; here is a junction with a gravel road.

Right on this road to TONGUE POINT LIGHTHOUSE SERVICE BASE, 0.7 m. Built on a projection extending into the wide mouth of the Columbia River, this base is the repair depot for buoys that guide navigators along the watercourses of the two states. Tongue Point was so named by Broughton in 1792. A proposal to establish a naval air base at this point, agitated for many years, was approved by Congress (1939) and funds appropriated for beginning construction.

On November 10 the Lewis and Clark party, unable to go far because of wind, camped on the northern shore nearly opposite this point. The camp was made on drift logs that floated at high tide. "nothing to eate but Pounded fish," Clark noted. "that night it Rained verry hard ... and continues this morning, the wind has luled and the waves are not high." The party moved on, but after ten miles the wind rose and they had to camp again on drift logs. Neighboring Indians appeared with fish. The camp was moved on the 12th to a slightly less dangerous place and Clark attempted to explore the nearby land on the 13th: "rained all day moderately. I am wet &C.&C." On the 14th: "The rain &c. which has continued without a longer intermition than 2 hours at a time for ten days past has destroy'd the robes and rotted nearly one half the fiew clothes the party has particularly the leather clothes." Clark was losing his patience by the 15th; even the pounded fish brought from the falls was becoming moldy. This was the eleventh day of rain and "the most disagreeable time I have experenced confined on the tempiest coast wet, where I can neither git out to hunt, return to a better situation, or proceed on." But they managed to move to a somewhat better camp that day and the men, salvaging boards from a deserted Indian camp, made rude shelters. The Indians began to give them too much attention, however, "I told those people ... that if any one of their nation stole any thing that the Senten'l whome they Saw near our baggage with his gun would most certainly Shute them, they all promised not to tuch a thing, and if any of their womin or bad boys took any thing to return it imediately and chastise them for it. I treated those people with great distance."

Horse sein fishing on the Columbia River (1296). Enlarge image.

Horse sein fishing on the Columbia River (1296). Enlarge image.

The party moved on to the northern shore of Baker Bay, where they remained for about ten days. From this point Clark went overland to explore, inviting those who wanted to see more of the "Ocian" to accompany him. Nine men, including York, the negro, still had enough energy to go.

On the 21st: "An old woman & Wife to a Cheif of the Chunnooks came and made a Camp near ours. She brought with her 6 young Squars (her daughters & nieces) I believe for the purpose of Gratifying the passions of the men of our party and receiving for those indulgience Such Small (presents) as She (the old woman) though proper to accept of."

"These people appear to View Sensuality as a Necessary evel, and do not appear to abhor it as a Crime in the unmarried State. The young females are fond of the attention of our men and appear to meet the sincere approbation of their friends and connections, for thus obtaining their favours."

Here the explorers had further evidence that English and American sailors had previously visited the Columbia. The tattooed name, "J. B. Bowman," was seen on the arm of a Chinook squaw. "Their legs are also picked with defferent figures," wrote Clark. "all those are considered by the natives of this quarter as handsom deckerations, and a woman without those deckorations is Considered as among the lower Class."

Three days later Lewis and Clark held a meeting to decide whether the party should go back to the falls, remain on the north shore or cross to the south side of the river for the winter. The members with one exception voted to move to the south shore, where they set up a temporary camp on Tongue Point. From this place they hunted a suitable site for the permanent camp.

ASTORIA, 104.5 m. (12 alt., 10,349 pop.).

Points of Interest: Fort Astoria, City Hall, Grave of D. McTavish, Flavel Mansion, Union Fishermen's Cooperative Packing Plant, Port of Astoria Terminal.

In Astoria US 30 meets US 101.