Real Threats to Oregon

The administrative area of Fort Stevens, near Astoria in 1942. (National Archives, image no. ARC 299673)

The administrative area of Fort Stevens, near Astoria in 1942. (National Archives, image no. ARC 299673) Racism and public pressure played key roles in the decision to remove people of Japanese descent from the West Coast. But officials weighed other factors as well. The threat of Japanese attack convinced leaders to designate a broad swath of territory along the Pacific Coast as a military theater of operations. Once that decision was made, it became easier to justify the removal of Japanese Americans, even loyal ones, in an effort to "simplify" the potentially dangerous military situation in the event that bombs fell. Officials could "not permit the risk of putting an unassimilated or partly assimilated people to an unpredictable test during an invasion by an army of their own race."

Footnote

1 Despite fears, an invasion never materialized. But, attacks did occur, including the shelling of Fort Stevens, two aerial bomb runs near Brookings, and balloon bombs such as the one that killed 6 near Bly.

Japanese Submarine Shells Fort Stevens

Events in Japan played a part in triggering the shelling of Fort Stevens near Astoria in 1942. In April, sixteen U.S. Army B-25 bombers managed to attack the Japanese home islands after being launched from the aircraft carrier

U.S.S. Hornet. The "Doolittle Raid," named for its leader, Lieutenant Colonel James H. Doolittle, was the most audacious operation undertaken by the United States in the young Pacific War. Conceived as a diversion that would also boost American and Allied morale, the raid generated strategic benefits that far outweighed its goals. Though it resulted in no tactical advantage, the shock of the attack left the Japanese high command deeply embarrassed. (

Watch a newsreel report about the Doolittle Raid

Watch a newsreel report about the Doolittle Raid - via youtube.com)

Long-range Japanese submarine I-25 shelled Fort Stevens in June 1942. Later that year it launched a seaplane that dropped bombs on the southern Oregon coast. (Image colorized)

Long-range Japanese submarine I-25 shelled Fort Stevens in June 1942. Later that year it launched a seaplane that dropped bombs on the southern Oregon coast. (Image colorized) Among their responses, Japanese military leaders adjusted their forces in the Pacific and dispatched a number of I-class long-range submarines across the Pacific to raid shipping off the American coast. The Japanese high command ordered submarines I-25 and I-26 to the Pacific Northwest to find and attack naval vessels headed to Alaska and the Aleutian Islands. On June 20, 1942, I-26 shelled the lighthouse at Estevan Point on Vancouver Island and I-25 torpedoed and shelled the freighter S.S. Fort Camosun off Cape Flattery. The freighter did not sink and rescuers towed it to safety in Neah Bay.

The next evening I-25 came in close to the coast through a fishing fleet to avoid minefields off the Columbia River and took position near Fort Stevens. The crew fired its 5.5 inch deck gun at the shore. Japanese Commander Meiji Tagami, who thought he was firing at a submarine base, later recalled: "In shooting at the land I did not use any gunsight at all--just shot." Meanwhile, at the fort the shots rang out as First Sergeant Lawrence Rude saw nothing but confusion: "I opened the door of my room and stood there in my drawers cussing at the guys to shut up. Some nut yells back that the Japs are shooting at us and then tore out of the barracks. It was a real madhouse."

Footnote

2

The 10-inch guns of Battery Russell at Fort Stevens near the baseball diamond damaged by a shell fired from a Japanese submarine. (National Archives, image no. ARC 299687)

The 10-inch guns of Battery Russell at Fort Stevens near the baseball diamond damaged by a shell fired from a Japanese submarine. (National Archives, image no. ARC 299687)

Despite the confusion, soldiers at the fort soon manned their guns and searchlights, and lookouts could see the submarine firing in the distance. But the enemy ship was inaccurately determined to be out of range, and the artillerymen never received permission to return fire. The fort's commander later claimed he didn't want to give away the precise location of the defenses to the enemy.

The I-25's shells left craters in the beach and marshland around Battery Russell at the fort, damaging only the backstop of the baseball diamond about 70 to 80 yards from the facility's big guns. A shell fragment also nicked a power line, causing it to fail later. Casualties amounted to one soldier who cut his head rushing to his battle station. By about midnight the attack ended and the enemy vessel sailed off to the west and north. While the submarine fired 17 shells, witnesses on land only heard between 9 and 14 rounds. Experts surmised that some shells might have been duds or fallen into the sea. Despite causing no significant damage, the attack certainly raised awareness of the threat of future strikes and went into the history books as the only hostile shelling of a military base on the U.S. mainland during World War II and the first since the War of 1812.

Soldiers examine a shell crater in a patch of skunk cabbage at Fort Stevens after an attack by a Japanese submarine. (National Archives, image no. ARC 299678)

Soldiers examine a shell crater in a patch of skunk cabbage at Fort Stevens after an attack by a Japanese submarine. (National Archives, image no. ARC 299678) Fallout from the attack in the Astoria area included demands from the local civilian population that clear warnings be given in the event of future shellings. As it was, civilian defense officials had no machinery to warn the population to take precautions. Moreover, the sounds of shell fire could be misleading as Clatsop County Defense Council Coordinator D.J. Lewis complained: "I personally heard every shell that was fired and recognized it for shellfire, but it certainly was not sufficiently alarming to cause me to get out of bed. What assurances have we that it wasn't practice at any of the Army or Navy posts around here, inasmuch as this has been known to happen?"

Footnote

3 In the end, military and civilian defense officials agreed to communicate more closely to warn citizens of an attack.

Japanese Plane Bombs Oregon Coast

Oregon made national headlines a few months later in two incidents that went down as the first aerial bombing of the United States mainland by a foreign power. Again the Japanese submarine I-25 was the source of the trouble. On Sept. 9, 1942 Japanese pilot Nobuo Fujita catapulted from the I-25 near the coast of southern Oregon aboard a seaplane and headed east toward Mt. Emily. His mission was to drop an incendiary (fire) bomb on the thick forest and cause a massive fire that would shock Americans and divert resources from fighting the war. Once over forested land, Fujita released the bomb, which struck leaving a crater about three feet in diameter and about one foot deep.

Forest officials examine fragments from a bomb dropped by a Japanese airplane in September 1942. (Folder 5, Box 17, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Forest officials examine fragments from a bomb dropped by a Japanese airplane in September 1942. (Folder 5, Box 17, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Meanwhile on the ground, forest service lookout Howard "Razz" Gardner watched the attack unfold. Looking into the dark skies just before dawn, Gardner heard what sounded to be a Model A Ford backfiring. Scanning the foggy skies, he caught glimpse of a small airplane circling above and called to the ranger station to report it. The operator who took the report assumed it was one of many patrol planes that passed up and down the coast.

Later as the fog lifted, Gardner spotted smoke and immediately sounded the alarm and called for help. He assumed the smoke was a result of lightning from a strong electrical storm the day before. After gathering equipment, he took off on a short cut through rugged terrain in the direction of the fire and was later joined by a coworker. They arrived at the scene where they found smoldering fires covering a circular area about 50 to 75 feet across. They quickly controlled the fires, examined the area, and found a crater at the center that showed signs of intense heat, including fused earth and rocks that resembled lava.

According to a later report: "The bomb in falling had struck a fir tree about six inches in diameter, much as though lightning had struck it, and the fin of the bomb had sheared off a tan oak tree five inches in diameter as cleanly as though it had been done with a heavy and sharp axe. Fragments of the bomb had been scattered over a radius of about 100 feet, one of the blazing pieces lodging in a decayed stub, setting it afire."

Footnote

4 After finding fragments of metal casings and thermite pellets, it was concluded that a bomb had caused the damage but it was assumed that it had been dropped accidentally by an American plane.

Anatomy of a Balloon Bomb

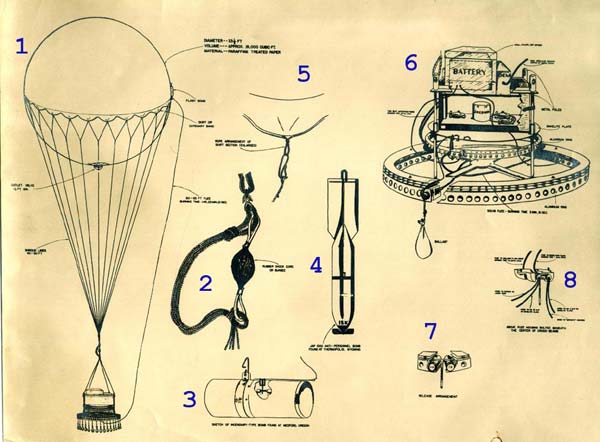

A diagram of balloon bomb parts. See below for description of parts. (Image courtesy Canada's Digital Collections)

Enlarge image Diagram of balloon bomb parts:

A diagram of balloon bomb parts. See below for description of parts. (Image courtesy Canada's Digital Collections)

Enlarge image Diagram of balloon bomb parts:

- The balloon: Diameter - 33 1/2 feet; volume - approx. 19,000 cubic feet; material - paraffin treated paper.

- Rubber shock cord or bungee.

- Sketch of incendiary-type bomb found at Medford, Oregon.

- Japanese 15KG antipersonnel bomb found at Thermopolis, Wyoming.

- Rope arrangement of skirt section (enlarged).

- Battery unit of balloon. Includes: metal poles, bakelite plate, aluminum ring, squib fuse, and aneroid barometer.

- Release arrangement.

- Fuse housing bolted beneath the center of the cross-beams.

Map showing balloon recoveries or sighting in North America (courtesy

National Geographic)

Map showing balloon recoveries or sighting in North America (courtesy

National Geographic)

The next day searchers found the bomb nose cone and a casing fragment with Japanese markings, confirming the identity. They gathered up the fragments and pellets, totaling about 60 pounds, and hauled them out for delivery to the Army lieutenant in charge of the Gold Beach detachment. Soon Army and FBI officials were conducting intensive interviews and swearing participants to secrecy. Meanwhile, the small town of Brookings to the south was buzzing with rumors. Residents heard of the bombing but could only speculate on details. Despite their efforts at secrecy, officials watched helplessly as newspapers across the country ran stories that included more details than the government had hoped to release. A second, similar seaplane attack at the end of September yielded similar results. If the forest had been as dry as normal for that time of year, the Japanese plan might have worked, leaving forest fires that diverted hundreds of fire fighters and large amounts of money from the war effort while triggering panic in the population.

Mary Reeder of the forest service shows fragments from a bomb dropped by a Japanese airplane in September 1942. (Folder 5, Box 17, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Mary Reeder of the forest service shows fragments from a bomb dropped by a Japanese airplane in September 1942. (Folder 5, Box 17, Defense Council Records, OSA) State Defense Council officials used the news to support their efforts to raise awareness about the possibility of enemy attack. State coordinator Jerrold Owen put it bluntly: "Morale among civilian defense workers was getting low because many of them believed 'it can't happen here.' Well, it did happen last Wednesday, so the workers can see now just what they are working for. We have been praying for just such an attack to shake people out of their lethargy." He went on to predict that "undoubtedly this small foray is but a forerunner of what may be expected in the future. Similar phosphorus bombs dropped on inflammable wooden buildings may be expected to cause extensive fires..." In response, Owen reminded readers that thousands of Oregonians had been training for a year to respond effectively to the threat posed by incendiary bombs.

Footnote

5

Balloons Carrying Bombs Drift Over Oregon

By November 1944, almost in a cruel and desperate afterthought to what seemed a lost cause, balloons launched from Japan and carrying explosive and incendiary bombs drifted east on the jet stream to the United States. Once again, the goal was to start forest fires and wreak devastation. On December 6 after a "mysterious explosion" in Wyoming, officials found balloon parts and bomb casing fragments from what had been a 33 pound high explosive bomb. During the next several months, Japan launched over 9,000 balloon bombs resulting in over 342 incidents registered throughout western United States and Canada. Oregon alone counted 45 balloon incidents. While they varied in size and design, many balloons measured about 100 feet in circumference and about 33 feet in diameter. The ingenious design helped them drift along the newly discovered fast moving jet stream at an average elevation of 30,000 feet.

Footnote

6

The balloons quickly attracted the attention of military and civilian defense officials across the West. Jack Hayes, the acting administrator of the State Defense Council acknowledged the problem of apathy commonly on display in the later months of the war: "Here in the northwest we have never lost our fear that the enemy would attempt to utilize our forests and unfavorable periods of weather as a means of attacking us here at home. In spite of the developing feeling the war was largely over and that Civilian Defense could be relegated to an almost inactive status."

Footnote

7 While tracking events related to balloon sightings, Hayes periodically summarized reports to Governor Earl Snell:

January 13, 1945

January 13, 1945

MEMORANDUM TO GOVERNOR SNELL:

During the course of the afternoon of Wednesday, January 10, a number of reports of Japanese balloons reached the military authorities. The first report involved the Alsea area and occurred shortly after noon. The second report came from residents in the area between Harrisburg and Coburg. The third report came from a State Police officer who apparently sighted the balloon in the vicinity of Cheshire. The fourth report came from the vicinity of Sutherlin. The fifth and most interesting and important, from the standpoint of the military authorities involved the pilot of a Grumman fighter from the Marine Base at Klamath Falls who reported to his base that he had sighted a balloon, was flying along side of the balloon, had taken pictures and intended to shoot it down.

This occurred at an altitude of 28,000 feet and when the attempt was made to shoot the balloon down the pilot found that his guns had frozen. By diving on the balloon from above, the pilot was able to bring the balloon down to an altitude of approximately 8,000 feet where he was joined by a non-combat ship from the same base. Many more pictures of the balloon were taken by this latter craft from all angles and the pilots reported that they had brought the balloon down, from an altitude of 6,000 feet by what they described as a "squeeze play".

The general area in which the balloon finally came to earth is described as in the area of Alturas, California. Search parties are in the area and it is expected that they will be able to recover the entire assembly. Previous incidents have not permitted complete recovery of all parts of the balloons because of the activation of the explosives which are part of the assembly and for this reason the Klamath Falls incident is looked forward to with great expectation by the military.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack A. Hayes, Acting AdministratorFootnote

8

(Image source: USAF Museum)

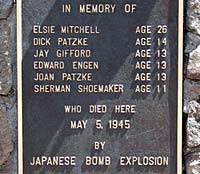

A monument marks the location of the bomb blast near Bly. (Image courtesy Sarah Lowrey)

A monument marks the location of the bomb blast near Bly. (Image courtesy Sarah Lowrey)

Japanese radio propaganda trumpeted the balloon bombs as being incredibly effective and claimed they had killed thousands.

The most tragic incident involving balloon bombs found a place in history as yielding the only deaths due to enemy action on mainland America during World War II. The events unfolded on May 5, 1945 as a pastor and his wife took five children for a picnic on a beautiful spring day east of Bly. As Reverend Archie Mitchell parked the car, he heard his pregnant wife, Elsye, call out: "Look what I found, dear." One of the children tried to remove the balloon from a tree and triggered the bomb. The force of the blast immediately filled the air with dust, pine needles, twigs, branches and dead logs. The mangled bodies of Elsye and the children were strewn around a crater three feet wide and one foot deep. Elsye lived briefly but most of the children died instantly.

Other balloon bombs were found in Oregon after this sad event but none caused death or injury. Japanese radio propaganda trumpeted the balloon bombs as being incredibly effective and claimed they killed thousands. In truth, the balloons disrupted routines as officials chased after sightings and reports, but failed to cause the widespread fires or panic anticipated by the Japanese.

Footnote

9 Most Americans didn't find out about the balloon bombs until after the war. The government censored the news to prevent the Japanese from finding out the effort was even partially successful.

Related Documents

Notes