"It Is Astonishing the Amount of Waste Being Gathered Up"

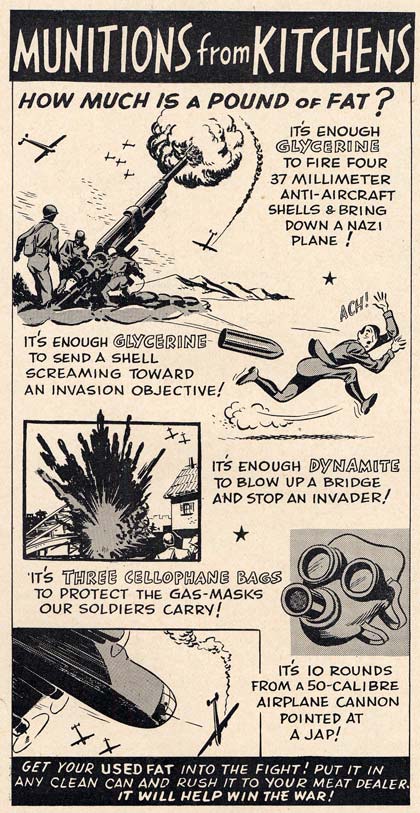

Kitchen fats were salvaged for the glycerine they contained. Glycerine was used in vital war products, most importantly explosives. (Folder 8, Box 30, Defense Council, OSA)

Enlarge image

Kitchen fats were salvaged for the glycerine they contained. Glycerine was used in vital war products, most importantly explosives. (Folder 8, Box 30, Defense Council, OSA)

Enlarge image Even before America's entry into World War II, and stretching over four years, a parade of scrap drives kept citizens busy. The drives started by collecting aluminum before moving to products such as tires, paper, tin, household fats, silk stockings and even coats for Russian refugees. Through it all, Oregonians combined a strong community spirit with fierce competition to salvage tons of products vital to the war effort. Salvaging represented another way Americans could contribute to the war effort in concert with other wartime programs. The process was again driven by shortages of vital materials such as rubber, tin and steel. In the overall effort, the conservation movement worked to reduce the consumption of war related materials; rationing attempted to fairly distribute the scarce commodities; and the salvage effort aimed to hunt down every pound of material that could be used to win the war.

Driving the Drives

Americans integrated salvaging tin cans into their daily lives. The caption to this cartoon reads: "Just try an' remember dear, flatten 'em AFTER they're empty!" (Folder 16, Box 28, Defense Council, OSA)

Americans integrated salvaging tin cans into their daily lives. The caption to this cartoon reads: "Just try an' remember dear, flatten 'em AFTER they're empty!" (Folder 16, Box 28, Defense Council, OSA) Government public relations campaigns spearheaded the effort to educate and mobilize every American to participate in scrap drives. Like the calls for conservation of resources, officials persistently reminded citizens how their seemingly inconsequential contribution would be monumental when multiplied by the efforts of other citizens. Jack Bristol, a Portland public relations expert, offered advice to an Oregon State Defense Council official to "drive home to the individual that what HE saves is important. One discarded toothpaste tube is admittedly not worth a tinker's damn --- but if ALL the tubes that are squeezed dry and discarded in Portland every morning were gotten together, they would constitute a respectable poundage of pure tin."

Letter from Jack BristolFootnote

1

Letter from Jack BristolFootnote

1

Comparisons drove home the value of salvaging materials. The amount of rubber salvaged from one tire could provide 20 parachute troopers with boots or make 12 gas masks. A thousand old galoshes collected during a scrap drive could provide the rubber to make a medium-sized bomber. And since the scrap drives would be weighing collected materials, officials provided weight comparisons to give people context for their efforts. For example, a light tank required 489 pounds of rubber--just the tracks alone consumed 317 pounds. And volunteers would have to work long and hard to outfit a battleship, needing 165,000 pounds to complete the job.

Chart of vital materials needed Footnote

2

Chart of vital materials needed Footnote

2

Officials didn't want people to destroy possessions that were still being used for their original purposes, but they made comparisons nonetheless: "How the beauty parlor goes to war; The iron that used to go into a single hair dryer is enough for six hand grenades." and "The Lumber in two average desks would provide enough material to build a trailer for a war worker."

Footnote

3

Comparing the salvaging efforts of the enemy with those of Americans could also spur higher achievement. In May 1943 officials quoted famed war correspondent Ernie Pyle who described German salvage work during a retreat:

In relation to the German retreat, an Oregon State Salvage Committee official added the commentary that "when you're running like heck, with an Allied bayonet close to your pants and still have to stop for salvage, its' importance is more than obvious. Salvage committees don't have to work under that handicap. We are not retreating. We face no dangers here save public apathy and indifference. But salvage is no less necessary on the peaceful home front in order to adequately support our boys on the war front who have to face the bayonets."

Footnote

5Organizing Salvage Efforts

Oregonians salvaged everything from rags to rubber to rope through a cooperative process involving the federal War Production Board (WPB) and the Oregon State Defense Council. Created in 1942, the 46 volunteer members of the Oregon State Salvage Board, under the WPB, planned programs and set policies and procedures for salvage efforts statewide. The defense council in turn was responsible for coordinating and mobilizing volunteer efforts in conjunction with local salvage committees.

Along with the highly publicized consumer scrap drives, WPB officials also sought out industrial scrap, old automobiles, and even special sources such as the rails from Portland's unused streetcar lines. Scrap drives came and went depending on the shortages of the moment. Rubber was urgently needed early in the war, leading to millions of old tires rolling into collection centers. Later, the need for rubber was less intense but the need for brass and bronze increased.

Footnote

6 Can Kitchen Fats Win the War?

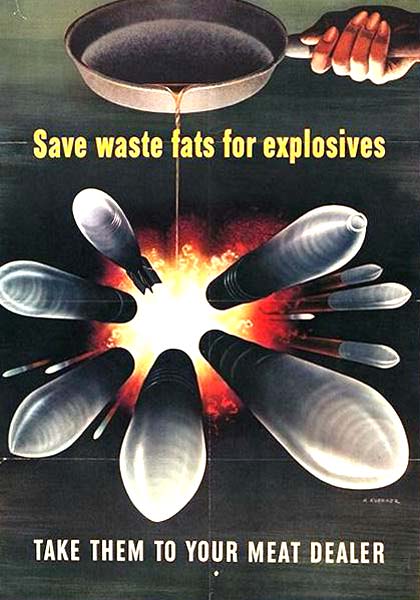

While a variety of scrap drives occurred, those related to kitchen fats and scrap paper illustrated the general process involved. Kitchen fats and greases seem odd materials to be fervently collecting in the midst of a world war, but officials had their reasons. The fats contained a significant amount of glycerine that could be used in explosives. Glycerine was valuable to the war effort in other ways, including as an antiseptic, a medicinal solvent, in cellophane and glassine packaging, and as treatment for sunburn and other skin irritations. The need for salvaging kitchen fats was heightened by the "complete shut-off of our vegetable oil supply from the Philippines and the Dutch East Indies by the Japanese...." Despite drastic curtailment of the use of glycerine in civilian products such as soap, cosmetics, lotions, candy, and gum, shortages persisted and fueled the long running salvage efforts.

Footnote

7

Posters made a dramatic connection between kitchen fats and the production of munitions. Graphic design image courtesy Northwestern University Library

Posters made a dramatic connection between kitchen fats and the production of munitions. Graphic design image courtesy Northwestern University Library As with other scrap drives, officials on the national and state levels set quotas for the amount of kitchen fats they expected to collect. The national quota for 1943, for example, was 200 million pounds. Oregon's share of the quota was 2,340,000 pounds, which averaged about 195,000 pounds per month. That was a tall order based on the state's past efforts that failed to top 64,000 per month. Still, state officials remained upbeat about their prospects of meeting the quota, saying that "despite the educational and promotional campaigns which have been carried on so splendidly by our county and unit salvage committees, the maximum available amount of fats has yet to be 'tapped.'" Even so, they acknowledged the challenge: "Needless to state, it's not going to be an easy job to attain these quotas, especially with the advent of meat rationing looming in the near future [presumably resulting in less kitchen fats]. BUT IT CAN BE DONE." There was no letup in the quota system--a later quota put Oregon's pride on the line for four million pounds a year.

Footnote

8

Salvage officials provided instructions, even quizzes, to help consumers save kitchen fats and greases and meet the quota: "You can help attain this quota, Mrs. Housewife, by saving your pan drippings, lard and vegetable shortening and all waste kitchen greases. Be sure to strain your fats, pour them into a wide-mouthed can, keep in a cool or refrigerated space and then, after you have one to two pounds of the materials, take them to your meat market. The butcher will pay you for them and start them on their way toward war industries."

Quiz about the need to save kitchen grease quiz

Footnote

9

Quiz about the need to save kitchen grease quiz

Footnote

9

Transportation of kitchen fats, once collected, was a problem for remote communities such as Lostine in Wallowa County. Volunteers there collected a large amount of tallow that had gone rancid before it could be delivered for rendering. A state official sternly reminded a Lostine salvage volunteer that "the government, on this kitchen Fats program, must have clean, clear, free-from-water fats; and if this quantity of tallow has been standing for quite sometime in Lostine, where probably there has been no refrigeration, we doubt very much if it would have any particular explosive glycerine value." The official suggested a call to the Consolidated Freightways Inc. office ten miles away in Enterprise to try to arrange for future pickups.

Footnote

10Paper Troopers March for Salvage

A Paper Trooper stands at attention, ready to salvage wagon loads of paper for the cause. (Folder 9, Box 30, Defense Council, OSA)

A Paper Trooper stands at attention, ready to salvage wagon loads of paper for the cause. (Folder 9, Box 30, Defense Council, OSA) Paper drives were a common form of salvage during the war. A 1942 estimate found the nation needed over 20 million tons of paper for the war and associated uses, with a goal of seven million tons coming from salvaged paper. The versatile product found its way into "several hundred thousand items used by the armed forces" such as blood plasma containers, K-ration cartons, shell casings, vaccine boxes, and bullet cartons. Again, officials took steps to limit civilian use. For instance, the amount of newsprint allocated to publishers was reduced to 75% of normal consumption. Still, by 1944, WPB chairman Donald M. Nelson was warning that "the shortage of wood pulp and available waste paper at the paper mills is becoming increasingly critical. The demands of the mills for paperboard containers and paper products for shipment of supplies to all battlefronts is growing constantly."

Footnote

11

Silk Stockings Go to War

In one of many unlikely pairings, ladies silk and nylon stockings played an important part in winning the war. At the time, silk was the only material out of which powder bags could be made. Powder bags contained the charge of gunpowder used in firing the "big guns." Silk was completely destroyed during the firing, unlike other materials that left a residue, which required cleaning the gun between shots.

The caption to this cartoon reads: "If I can put up with painted stockings, what's wrong with having your socks mended likewise?" (Folder 5, Box 30, Defense Council, OSA) Nylon stockings could be melted, respun into nylon thread, and manufactured into war products such as parachutes. With their silk and nylon stockings drafted into the war effort, stylish women needed alternatives. Many used leg make-up, otherwise know as "bottled stockings," that could last up to 3 days assuming no baths were taken. Some women even used eyebrow pencils to paint faux stocking seams on the backs of their legs. Sacrifice, and ingenuity it seems, were boundless!

The caption to this cartoon reads: "If I can put up with painted stockings, what's wrong with having your socks mended likewise?" (Folder 5, Box 30, Defense Council, OSA) Nylon stockings could be melted, respun into nylon thread, and manufactured into war products such as parachutes. With their silk and nylon stockings drafted into the war effort, stylish women needed alternatives. Many used leg make-up, otherwise know as "bottled stockings," that could last up to 3 days assuming no baths were taken. Some women even used eyebrow pencils to paint faux stocking seams on the backs of their legs. Sacrifice, and ingenuity it seems, were boundless!

Question and answer about stockingsFootnote

19

Question and answer about stockingsFootnote

19

The WPB studied reports of school waste paper salvage campaigns across the country to put together a new program designed to enhance efforts by students. The program created "an army of paper salvagers" called "Paper Troopers." According to program literature, the name was no accident, since it had "a resemblance to the name Paratroopers, those daring raiders dropped from the sky behind enemy lines, and should, therefore, have a tremendous appeal to pupils. Boys nowadays live in terms of fighting adventure and the paper trooper emblem will make a strong appeal to them. It will appeal to girls, too." Students who excelled at paper collection could "advance in rank" and earn additional chevrons that served as "public acknowledgement of their achievements." They could also earn certificates of merit for themselves and their schools.

Footnote

12

WPB officials urged teachers to get involved too, saying that "almost every teacher can find some way of working the Waste Paper Salvage theme into his current classroom assignments." For example, in dramatics class the students could do a skit on "the story of waste paper and the war." Social studies teachers could highlight the role of paper in modern life and arithmetic teachers could have their students account for the paper received and the funds resulting from its sale, while shop teachers could challenge pupils to construct a paper baler. Because of "the rising rate of juvenile delinquency," officials also wanted to set up activities during school vacations. They reasoned that the continuing work would serve two purposes: it would add to the paper salvage totals; and it would help students "develop their competence as youthful citizens and turn their energies into wholesome constructive channels at a period when there is great pressure to divert them into non-constructive and even anti-social channels."

Footnote

13Harnessing the Community Spirit

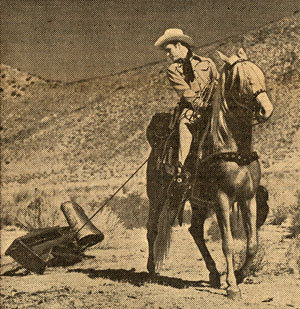

Cowboy movie star Roy Rogers hauls in scrap from the range for the salvage effort. (Folder 16, Box 28, Defense Council, OSA)

Cowboy movie star Roy Rogers hauls in scrap from the range for the salvage effort. (Folder 16, Box 28, Defense Council, OSA) Paper Troopers and other salvage programs harnessed cooperative and competitive instincts within communities. Each level, from the state down to the neighborhood or school, saw constant jockeying for bragging rights. Thus, all of the citizens of Oregon could be rightfully proud of the state's ranking of number two out of all 48 states in both iron/steel and silk/nylon stocking salvage on a per capita basis in 1943.

Footnote

14 Tiny Powers High School, with an enrollment of 45, won acclaim for what was thought to be the national record for the collection of scrap by students in 1942, with each child collecting nearly 14,000 pounds. Meanwhile, Portland's Lincoln High School collected 200 tons of scrap making it the champion of total poundage. This sort of friendly competition continued throughout the war as "scrappers" of all ages vied for evidence of their prowess and patriotism.

Footnote

15

Meanwhile, "one thousand Klamath Falls kiddies, each bearing a batch of tin cans, bore down on a local theater" for another matinee, this time in conjunction with the Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, and Campfire Girls organizations.

State salvage officials fanned the flames of community rivalries by publishing local accomplishments. Readers learned that young people in Corvallis held a "scrap matinee" at a local theater and gathered a truckload of "much-needed" copper, brass and aluminum. Meanwhile, "one thousand Klamath Falls kiddies, each bearing a batch of tin cans, bore down on a local theater" for another matinee, this time in conjunction with the Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, and Campfire Girls organizations. By the end of the show, 5,250 pounds of cans had been salvaged. Clatsop County contributed over 12 tons of waste fats and nearly 1,000 pounds of silk and nylon stockings while Portland put up big numbers by filling 23 train carloads of tin.

Footnote

16

Local efforts, such as those in the La Grande area, proved inspiring as J.H. Bratton reported to the Oregon State Defense Council in 1942: "The salvage program is in full blast and the committees are obtaining splendid cooperation from the public. One wrecking concern informed me that they are turning in around 12 tons of old tires and that they ship a carload of scrap-iron every other day. All service stations are piled high with rubber salvage. I have met a number of farmers bringing in scrap-iron and rubber in pick-ups and trucks on the road. It is astonishing the amount of waste that is being gathered up."

Footnote

17