"If It Grows a Fine Crop of Flowers or Weeds, It's Soil"

Officials reminded Americans that a well planned Victory Garden was not only patriotic, but

could provide a family with nutritious and tasty food. (Folder 18, Box 28, Defense Council, OSA)

Officials reminded Americans that a well planned Victory Garden was not only patriotic, but

could provide a family with nutritious and tasty food. (Folder 18, Box 28, Defense Council, OSA)

America had a reputation as a land of plenty, but World War II challenged the nation's ability to grow and

distribute food. Millions of farmers and farm laborers

streamed into the military or to high paying defense industry jobs, leading to a

severe farm labor shortage. At the same time, the United States bore the

additional responsibility of providing vast amounts of food to allies such as Britain, China, and the Soviet Union, hoping to prevent their collapse.

To boost production and ease the strain on the transportation system,

Victory Gardens sprouted across the country, as many Americans

learned the pleasure of getting dirty for a patriotic cause.

Why Victory Gardens?

Officials cited several reasons why Americans should grow their own food. Even with boosts in farm production goals, the needs were "so great that every food production resource must be mobilized to meet the demand." About 25%

of total food production in 1943 went to the armed forces and

the allies, with each soldier needing a ton of food a year. Moreover, partly because of tin shortages and the military needs, canned food was in short supply and came under rationing regulations. This left millions of Americans habituated to eating canned foods looking at increasingly bare grocery store shelves. Fresh fruits and vegetables were not rationed but, according to officials, "the wartime burden on the Nation's transportation system will make it impossible to ship over long distances the normal amount of fresh vegetables and fruits, especially the more bulky vegetables. This will require production of more of the civilian supplies close to consuming areas."

Footnote 1

Authorities also provided citizens with selfish reasons to have a Victory Garden. Home gardeners wouldn't have to worry about crop failures in other parts of the country or transportation "bottlenecks" limiting supply. They would save money too since "even a small garden, if well planned and tended, will yield $25 to $50 worth of vegetables." People with Victory Gardens would be healthier since "there's nothing like exercise and better meals to improve your health, which is doubly important in wartime." And, officials asserted, home grown food is tastier: "It's not only because you raised it yourself, with sweat and care. Vegetables and fruits do have a better flavor when they are really fresh, as they are when they come right from the garden." And for those suffering from wartime anxiety, "there isn't a better hobby for lots of people. It makes you feel good. It relaxes your nerves. It's a family enterprise that brings together father, mother, son and daughter." Even the community benefits of gardening could make the individual feel better since gardens "promote neighborliness, sociability, cooperation." With home gardeners providing 40%

of the country's fresh vegetables by 1944, the individual could feel patriotic about the contribution.

Footnote 2Where and How to Start

A woman snacks on a carrot, part of a basketful of bounty from a Victory Garden. Americans grew over 20 million gardens during the war. (Folder 13, Box 30, Defense Council, OSA)

A woman snacks on a carrot, part of a basketful of bounty from a Victory Garden. Americans grew over 20 million gardens during the war. (Folder 13, Box 30, Defense Council, OSA)

The U.S. Department of Agriculture promoted Victory Gardens in four major settings. Of course, farms were obvious candidates. Farmers were encouraged

to start or expand vegetable gardens and, where possible,

plant strawberries, bush fruit, and suitable fruit trees. By 1944 Americans tended

over six million farm gardens.Town and suburban gardeners were called on to plant

in their back yards or any other "open sunny garden space." Suburban

property owners, with typically larger lots, were asked to plant more fruit

"wherever space permits." While some people living in cities,

such as Portland, could plant in back yards or street right of ways, many relied

on community gardens. These could be set up on vacant lots that were recommended

to be 30 by 50 feet or larger and "accessible by bus or street car."

Officials also called on schools to grow gardens, hoping to supply school lunches

in the process. During the long summer vacation, schools could hire local boys to

cultivate the gardens "under the watchful supervision of the instructor or a gardener."

Footnote 3 Overall, American's responded by tending over 20 million Victory Gardens during the war.

Officials also offered advice on who should grow, or not grow, a Victory Garden.

Rex Putnam, Oregon Superintendent of Public Instruction, echoed the caution

for fair weather gardeners: "Gardens will not grow on hopes and good intentions. A good garden will require space, fertile soil, and faithful care. Lack of

the latter causes many gardens to languish. Anyone disinclined to care for the garden he plants should desist from gardening 'for the duration' as this is no time to waste precious seed, fertilizer, and insecticides."

Footnote 4

Families enjoyed planning their Victory Garden for the year. Experts

offered

advice to novices on how to get the most out of their plot. (Folder 13, Box 30, Defense Council, OSA)

Families enjoyed planning their Victory Garden for the year. Experts

offered

advice to novices on how to get the most out of their plot. (Folder 13, Box 30, Defense Council, OSA)

Once they were sure they wanted to garden, citizens had access to a wealth of information about how to proceed. The literature ranged from

basic to very detailed since it was designed to help everyone from the first time gardener to the long time gardener looking to increase yields or try new crops. Most advice told gardeners to choose the plot wisely but chemical soil analysis

wasn't needed because "if it grows a fine crop of flowers or weeds, it's soil." Still, they were to be wary of "the usual kind of city lots where soil is mostly cinders and rubbish." Gardeners were admonished to avoid using too much seed and planting too much of one thing. Too much shade could also doom

a location.

Planning ahead was important so rookie gardeners were told not to let tall crops shade short ones: "Plant climbers, like beans,

to the north; short ones, to the south." Of course, to be

vigilant against weeds and insects they had to "be

ready with spray gun and duster and the proper death-dealing ammunition."

Footnote 5

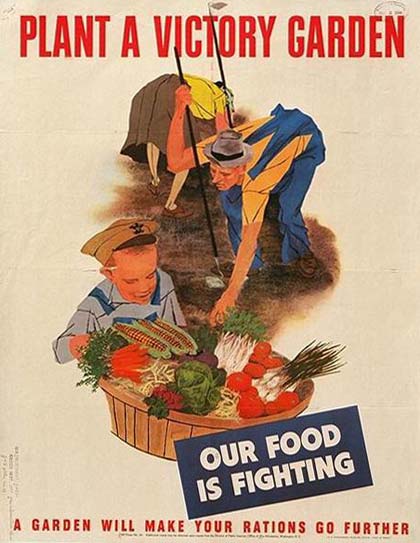

Officials promoted

Victory Gardens as a way to stretch valuable rations. As an added benefit, it was way

for families to spend time together. Victory Garden image courtesy Northwestern University Library

Officials promoted

Victory Gardens as a way to stretch valuable rations. As an added benefit, it was way

for families to spend time together. Victory Garden image courtesy Northwestern University Library

Victory Gardens proved popular with Oregonians, who soon organized around the state. The Oregon Victory Garden Advisory Committee formed in 1942, consisting of representatives from federal and state agencies as well as groups such as the State Grange, 4-H Clubs, State Federation of Garden Clubs, and the State Horticultural Society. The Oregon State College Extension Service also hosted conferences and supplied

advice to new gardeners. During 1942, 16 counties held their own garden conferences with the help of county extension agents who issued garden guidelines customized

for their local climatic conditions. Meanwhile, neighborhood leaders were charged with distributing Victory Garden information to individual homes and radio broadcasts filled the airwaves with related information. National and state goals aimed at increased participation. For example, Oregon's goal of 59,000 Victory Gardens by the end of 1942 represented a 38%

increase over the previous goal.

Footnote 6

Local Experiences

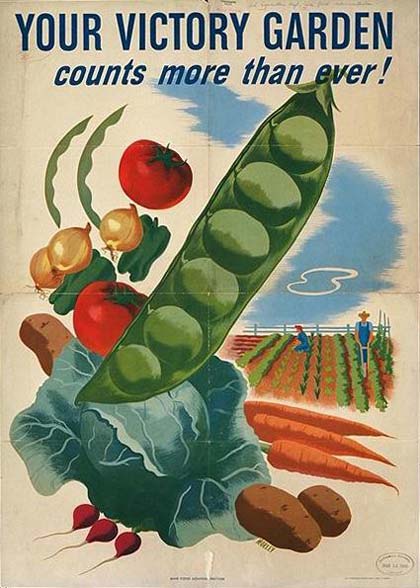

Victory Gardens provided nutritious food for healthier meals. Your Victory Garden image courtesy Northwestern University Library

Victory Gardens provided nutritious food for healthier meals. Your Victory Garden image courtesy Northwestern University Library

While Victory Gardens grew around the state, they perhaps had their biggest impact in the urban setting of the Portland area. Thousands of new gardeners took to the plots. By May 1943, children alone were cultivating an amazing 135 acres of land, with more than 2,000 young people participating in the Victory Garden program. Schools took part by instructing 5th

grade through high school students during class time. The actual gardening was

done outside of school hours with each student

registered for an individual garden area. "Important-looking" V-garden signs that included no trespassing warnings were also given to each student. Concerned with rising juvenile delinquency, school authorities thought it was "better for children to have gardens than to be entirely unoccupied when school is over." At least one teacher, Miss Maude Mattley, thought children made good gardeners: "...it is safe to say that most of these young gardeners were far better prepared to start out with a hoe and a rake than the average adult victory gardener."

Footnote 7

"We try to keep the subject matter seasonal and very practical. What to do this week, what things to plant, how to care for the things already set out...just whatever is timely."

Meanwhile, adults streamed into Portland area

classes to become better gardeners. The local victory garden committee offered the free classes throughout the city. By May 1943, 12 classes were underway with more planned. While some children attended, most students ranged from 20 years old to over 70.

Taught by experienced volunteers, the weekly classes took place in schools,

private homes, or "wherever the requisite space is available." Lessons

highlighted each class but question and answer sessions were a popular

component. According to one teacher: "We try to keep the subject

matter seasonal and very practical. What to do this week, what things to plant, how to care for the things already set out...just whatever is timely." While many

classes were held in the evening, some daytime classes were offered for the defense industry workers on "swing shift," often from 4 p.m. to midnight. The classes were becoming popular in the defense housing areas and organizers wanted to "start a class for gardeners in Vanport City and Kaiserville, and have more than 200 names signed up for membership."

Footnote 8