"Let's Face the Facts!"

Ambulances played a key role in civilian defense plans to respond to an enemy attack. This 1939 Ford sedan was converted to carry a 4-stretcher ambulance body.

Ambulances played a key role in civilian defense plans to respond to an enemy attack. This 1939 Ford sedan was converted to carry a 4-stretcher ambulance body.

Ambulance specifications in letter from Fred T. Foard, M.D., Folder 8, Box 22, Defense Council, OSA

Ambulance specifications in letter from Fred T. Foard, M.D., Folder 8, Box 22, Defense Council, OSA If the worst happened and enemy bombs left massive devastation and casualties in Oregon, officials knew they would have an uphill battle to respond effectively. Large numbers of rescue, ambulance, and medical personnel would be needed. But the need for these professions for overseas duty in the war had drained their ranks on the home front. For instance, about 30% of Portland's doctors had already left for active service. Civilian defense authorities recognized the size of their challenge: "Let's face the facts! For over a year now, we've told you Nurse's Aides are needed. With the military needing at least 3,000 trained nurses a month, we are facing a critical civilian nursing shortage. An enemy raid would cause wide-spread disaster, and there is nothing on which to base our complacency that some other emergency may not break out tomorrow, an emergency which we must be prepared to meet."

Footnote

1 Coordinating Limited Resources

Rescuers had to work quickly after an attack to get victims to a hospital or casualty station. (Folder 2, Box 34, Defense Council, OSA)

Rescuers had to work quickly after an attack to get victims to a hospital or casualty station. (Folder 2, Box 34, Defense Council, OSA) State Defense Council officials coordinated with a range of groups, including the Red Cross, hospitals, doctors, nurses, and emergency services organizations to develop sophisticated response plans. Hospitals across the state undertook detailed top to bottom surveys of their facilities and staff to look for weaknesses and improve their capacity. Thousands of people volunteered to work in casualty stations designed in case of an attack to act as local shelters where victims could get temporary medical care before returning home or to emergency housing. Others outfitted and stocked medical supply depots in the vicinity of casualty stations. In case of gas attack, officials planned decontamination or cleansing stations near major hospitals. And the State Medical Disaster Division of the State Defense Council planned base hospitals located in rural "non-target" areas, mostly in eastern Oregon, where evacuees could be moved for safe treatment.

Base hospitals bulletinFootnote

2

Base hospitals bulletinFootnote

2 Coping With Staff Shortages

Doctors, nurses and other hospital workers put in long hours of overtime to cope with the staff shortages. To lessen the burden, the Oregon State Medical Society encouraged citizens to be responsible when asking for help from doctors and nurses. For example: "Don't ask for house calls by a doctor unless absolutely necessary." Patients were also asked to call their doctor instead of insisting on a visit in many cases. At the hospital, friends and relatives of patients were admonished not to "ask for guest meals in the patient's room, [and] don't sit on the beds - you soil them." They were also asked to take care of the flowers they brought, thus "freeing a nurse for the serious business of caring for the sick."

Footnote

3

(Image source: Folder 5, Box 22, Defense Council Records, OSA)

(Image source: Folder 5, Box 22, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Another way to help was to recruit and train more staff. This was a challenge since there were relatively high paying defense jobs available. Medical services recruiters also competed with other civilian protection or war services opportunities for volunteers, such as aircraft warning ground observers and war bond drive workers. Many potential volunteers confessed to being queasy at the thought of working around injured or sick patients. Still, with extensive publicity on the radio and in magazines and newspapers, officials managed to coax thousands of women to pitch in with questions such as: "Now honestly, which is the most important -- your pre-war standard of house-keeping, or that sick child?"

Footnote

4 The Oregon Womens Ambulance Corps

While men also volunteered, it was women who made up for most of the shortages in medically related services. Two important examples were the Oregon Womens Ambulance Corps and the expanded role of nurses aides. The Oregon Womens Ambulance Corps described itself as "a non-profit, and non-political organization of intelligent women who have banded together for training in the fields in which women could be most useful in any local or national emergency." The group, which assumed a quasi-military structure, was headed by Colonel Ann Schmeer, while its advisory board was populated by men. The corps accepted female U.S. citizens who were over 18 years old, provided they presented reasonable personal appearance, showed good moral character, and had a driver license. Mandatory training included military drill, first aid and litter drill, communication (signaling, short wave, Morse code, etc.), motor mechanics, and fire fighting. Members were called on to earn a chauffeur's license as well.

Footnote

5 Training and Civic Activities

Corps members spent time training and drilling for emergency duties, but they also contributed to the community in other ways. Local units could be formed with the presence of 12 qualified women and by the middle of 1941 nine units were up and running. Some of these, such as in Portland, were massive. The Portland unit alone counted hundreds of members organized into dozens of categories such as drivers, truck drivers, standard, advanced, and medical first aid, nursing, teletype operators, typists, stenographers, clerks, firefighters, motor mechanics, seamstresses, cooks, beauticians and musicians.

Footnote

6

(Image source: Folder 5, Box 22, Defense Council Records, OSA)

(Image source: Folder 5, Box 22, Defense Council Records, OSA) In early 1942 these units reported significant civic activities: In Ocean Lake corps members carried out a paper drive and took part in a "24-hour vigil" at an aircraft observation post. Salem members organized the first bicycle first aid squad in the state and furnished instructors on chemical warfare and first aid. The Pendleton corps raised $300 toward a city ambulance while Eugene members took part in a civilian defense round table on the radio. The Portland contingent provided 5 first aid instructors to the Red Cross and reported that "two instructors alone teach more than 500 persons per week." The Portland report also called attention to their work on the "Americanization" program and noted that "Major Goble is instructing at Jantzen Knitting Mills in chemical warfare as it affects civilians."

Footnote

7 Working in a Man's World

The Ambulance Corps experienced a few rough spots trying to fit into the male dominated world of civilian protection. After a long period of trying to "get a place" for the Ambulance Corps' Portland Headquarters in the Portland and Multnomah County Defense Council offices, Colonel Schmeer reported that "the going has been pretty slow. Now, however, there seems to be some possibility of working out something -- if the girls will wear skirts instead of slacks. I personally think skirts are much nicer but for the life of me I don't see how they contribute to civilian defense. If the Portland girls are willing to abandon slacks for skirts Capt. Keegan seems willing to make some kind of deal to use them." Schmeer was philosophical about their role: "We find much to inspire us and a great deal of progress, often made under the handicap of little public interest, and sometimes under actual ridicule or criticism.”

Footnote

8 Nurses Aides Fill Staffing Gaps

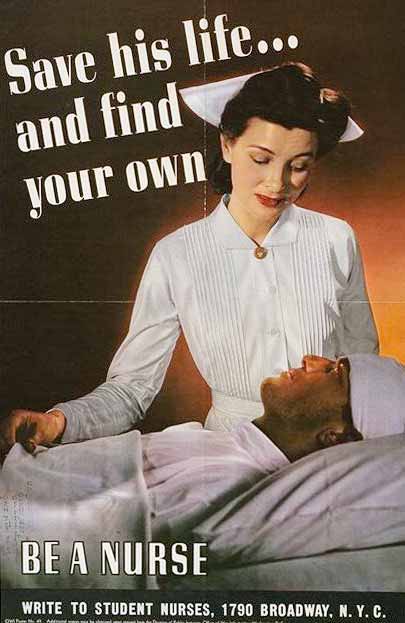

Nurses were recruited for both overseas and domestic service. Uniformed nurse photo courtesy Northwestern University Library

Nurses were recruited for both overseas and domestic service. Uniformed nurse photo courtesy Northwestern University Library Nurses aides played a vital role in filling staffing gaps in hospitals across Oregon. But the shift to using more nurses aides met resistance from traditional elements of the medical professions. One convert, Emily Heaton, the superintendent of Good Samaritan Hospital in Portland, described the change: "In the past, hospitals have drawn a circle around the patient and his bed. They have said, 'No one except the professionally trained may cross this line to care for our sick patients.' When the Red Cross proposed to train a group of volunteers to help with this care, we were skeptical. 'Patients won't accept them. We won't be able to depend on them,' was said. WE WERE WRONG! They are today accepted within this circle as no other non-professional worker ever has been. We welcome them! We depend on them! We wish there were more of them -- Bless them!"

Footnote

9

Nurses aides filled numerous jobs in health care. In hospitals they made beds, took temperatures and pulse rates, assisted with dressing wounds, and helped apply casts, among other duties. This helped free registered nurses for pressing duties such as caring for more severely sick or injured patients. But volunteers quickly branched into other areas. In Marion County five aides did visiting nurse work under the public health officer. Others assisted the health officer at preschool, school, immunization, venereal, and dental clinics in the county. Ten more aides worked at a mobile unit of the local blood bank. And 56 nurses aides completed special training to work with polio victims while others volunteered to work in the state tuberculosis hospital.

Footnote

10

Meritorious Service to the Cause

The aides put in tremendous hours in their volunteer work. By the middle of 1944, Marion County's 164 nurses aides had contributed nearly 23,000 hours of service. In recognition, the Red Cross honored the Marion County chapter of nurses aides for having the best volunteer record of service on the West Coast and the 3rd best in the nation. Other aides garnered recognition as well. Laura Wilson of Portland singlehandedly volunteered more than 2,100 hours by September 1943. According to

The Oregonian newspaper, which gave her their "citation of the week," Wilson's superiors said that she had "many of the most desirable qualities of a good nurse. She is soft-voiced and gentle; quietly competent; she is genuinely concerned about human suffering, eager to do what she can to ease it." The newspaper noted that "because she once mastered the intricacies of the Russian tongue, she has been particularly valuable in assisting in the care of Russian seamen who have been patients in the hospitals where she has worked."

Footnote

11

Displaying a "Sense of the Appropriate"

Nurses aides were responsible for following countless regulations, policies and procedures in their work. Some notable hospital regulations in Salem covered their appearance. Aides were expected to arrive with a starched cap, fresh blouse, and "spotless pinafore." They were to wear no jewelry other than wedding or engagement rings - "never ear-rings." Although no rule forbade the use of cosmetics while on duty, there was the expectation "that your own knowledge of the 'fitness of things' will direct you in using these discriminately and sparingly" so that the aide could display her 'sense of the appropriate.'"

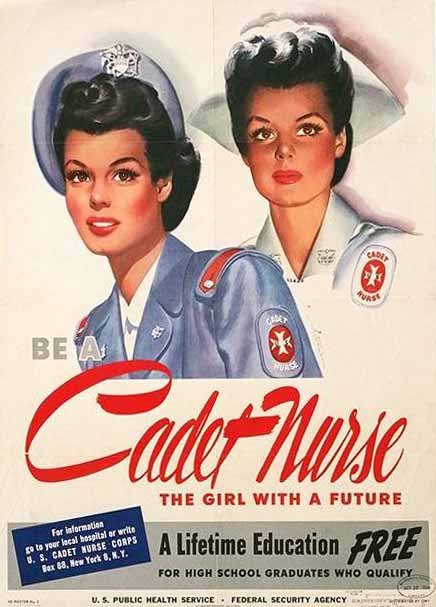

Recruiters promoted the stylish appearance of uniforms for nurses and female medical services workers. Cadet Nurse graphic courtesy Northwestern University Library

Recruiters promoted the stylish appearance of uniforms for nurses and female medical services workers. Cadet Nurse graphic courtesy Northwestern University Library Among other restrictions, red fingernail polish was discouraged while pastel hues were okay. Perfume drew attention as the regulations noted that: "the pungent sweet odors of some perfumes are very nauseating to patients." Because of this, the nurses aide needed to "resort to other measures in keeping her body fragrantly fresh." The solutions offered were "bathing more frequently, the consistent use of a good deodorant, and cologne or toilet water sprays of lighter fragrances." Of course, smoking and drinking on duty were prohibited.

Footnote

12 The Natural Pecking Order

Professional ethics were part of the regulations for nurses aides as well. Many instructions described their role in the strict hierarchy of the hospital setting. For example, they were expected to never be insubordinate to a nurse: "If she gives you orders which are directly inverse to those which you were taught, never question her authority in front of the patient." The respect was due because of the training and experience nurses accrued: "A registered nurse has studied and practiced her profession eight hours a day for three years as compared to the ten eight hour days it takes to complete a Nurses Aide course." Likewise, the doctor took his place at the top of the pecking order: "Because of his many years of study and preparation for his life profession, because of his selflessness in his absorbing concern for the health and welfare of others..., a Doctor deserves the revered place he has in any community. This respect of higher learning we make known by a simple gesture. When a Doctor approaches the desk and you are sitting, simply rise."

Footnote

13 Related Documents

"S.O.S. Pinafore"

"S.O.S. Pinafore" Newsletter, Marion County Chapter Nurses Aides, July 18, 1944. Folder 12, Box 19, Defense Council Records, OSA.

Notes