"The Saboteur May Be Sly and Furtive"

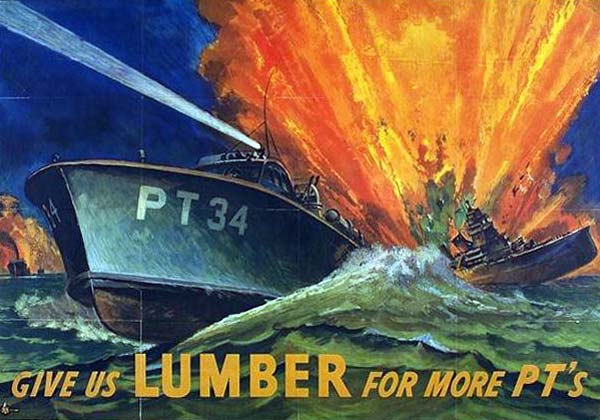

A Navy PT boat in the midst of battle dramatized the need for Oregon's wood products in this government poster.

PT torpedo boat image courtesy Northwestern University Library

A Navy PT boat in the midst of battle dramatized the need for Oregon's wood products in this government poster.

PT torpedo boat image courtesy Northwestern University Library Wood products and Liberty transport ships comprised two of Oregon's significant contributions to the war effort. Their sources also represented two of the state's most vulnerable targets for attack or sabotage. Oregon's vast forest lands and sprawling shipyards and mills ranked high in the minds of military and civilian defense officials as vital assets in need of protection. But the Army couldn't supply the tens of thousands of soldiers necessary to guard forests that reached as far as the eye could see from fire or attack. And they couldn't spare enough troops to circle shipyards and other plants and factories that supplied the war effort. Even if they could, these facilities would still be vulnerable to infiltration by saboteurs and spies bent on destroying them from inside or stealing crucial secrets. Instead, civilian defense programs had to fight the threat by remaining vigilant and educating those who worked in the forests, shipyards and other vital state assets. The stakes were high - if forest and plant protection programs succeeded, production would be maximized and millions of Americans fighting in the war would have every advantage possible.

Forest Protection

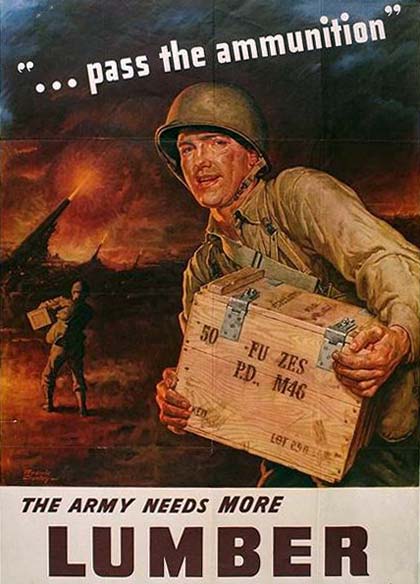

The need for ammunition boxes, pallets, and other wood products kept workers in Oregon's forest busy.

Illustrated image courtesy Northwestern University Library

The need for ammunition boxes, pallets, and other wood products kept workers in Oregon's forest busy.

Illustrated image courtesy Northwestern University Library Protecting Oregon's forests from fire damage, already a priority, took on more importance after the federal War Production Board declared lumber to be a critical war material, thus sharply curtailing its use for any purpose other than defense. Wood from the forests of the Pacific Northwest, particularly Douglas fir, went into countless applications such as cantonments and defense housing and it was rapidly replacing steel in building warehouses, airplane hangers, factories, docks and other structures. Some of this was a result of a shortage of steel, but it was also made possible by engineering developments such as the "ring connector method of timber framing." Douglas fir was used as decking on battleships and airplane carriers, in patrol boats, in Navy mine sweepers and submarine chasers, and in fleets of inland and coastal barges. Moreover, five Northwest timber species found there way into American and British airplanes.

Footnote

1 Even products as mundane as pallets and shipping crates, not to mention the countless reams of paper for the fast-growing military and civilian bureaucracies, relied on Oregon's forests.

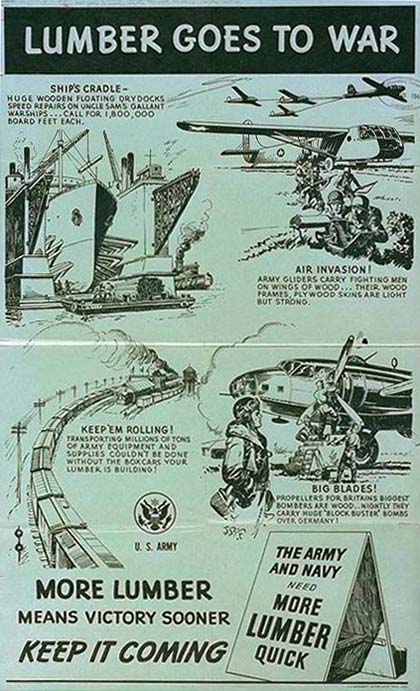

This poster shows ways "lumber goes to war."

Large image courtesy Northwestern University Library

This poster shows ways "lumber goes to war."

Large image courtesy Northwestern University Library Increased logging activity to meet the defense demand coupled with fear of sabotage or enemy attack caused officials to develop the Forest Fire Fighter Service (FFFS) in 1942. Augmenting the work of federal and state forestry agencies, the goal of the new organization was to prevent and control any fires that threatened forest land and timber resources. Operating under the federal Office of Civilian Defense, the service worked with state officials, who appointed coordinators. On the local level, coordinators appointed squad leaders who controlled working units of 8-10 fire fighters. Each member was required to complete a minimum of 12 hours of training to be certified, although this could be modified to suit local conditions since "many loggers, ranchers, and others because of past experience will be more useful than inexperienced persons with many times 12 hours of training." New fire fighters studied the forest fire control plan for their local area; common causes for forest fires; fire behavior as affected by topography, cover, and weather; safe use of hand tools; and other topics. As part of the job, they also passed along elements of their training to their neighbors, school children and the public. This outreach effort enlisted even more people in the cause of forest protection, providing more eyes and ears on the lookout for fire or suspicious behavior in and around the state's forests.

Footnote

2

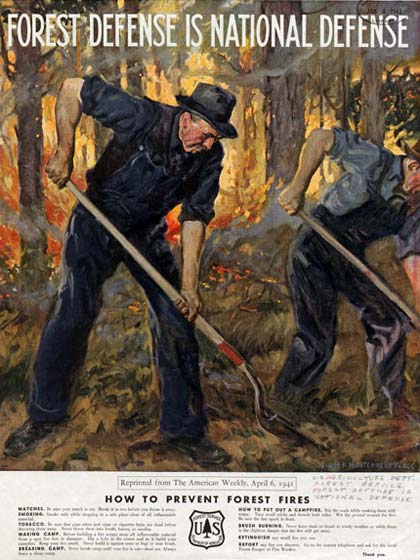

This illustration shows civilians working on fire lines for national defense. (Oversize Records, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Enlarge image

This illustration shows civilians working on fire lines for national defense. (Oversize Records, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Enlarge image Certainly Oregon communities and towns adjacent to forest areas already had experience with fighting forest fires. In many cases it was custom for business and men from nearby towns to help control fires without the aid of any formal organization such as the Forest Fire Fighter Service. Hoping to build on this tradition of service, Arthur King, Oregon coordinator of the FFFS, wanted to recruit these individuals into the fold. He reasoned that the resulting effort would be more effective because of enhanced training and organization and at the same time would "give the volunteers the recognition of belonging to a national civilian defense organization." King targeted local sportsmen as well as members of the American Legion and service and fraternal organizations. He also sought older members of the Future Farmers of America and 4-H clubs along with older boy scouts.

Footnote

3

In addition to recruiting volunteers to work on the fire lines, state FFFS officials looked to develop forest protection specialists. These included emergency lookouts, patrolmen, bulldozer operators, power pump operators, truck drivers, tool repairmen and others. They also sought to enlist the service of women, albeit on a limited basis. Josephine County drew national attention in 1942 for organizing and training female "canteen crews" and state officials wanted to expand this to other areas of Oregon. They also hoped to interest women in other work related to forest protection such as timekeeping, warehouse duties, and light truck driving.

Footnote

4 Plant Protection

Officials warned that saboteurs could ruin factory equipment while making it appear to result from natural causes. (Folder 23, Box 34, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Officials warned that saboteurs could ruin factory equipment while making it appear to result from natural causes. (Folder 23, Box 34, Defense Council Records, OSA) The concept of plant protection brought together strategies and lessons learned in civilian defense categories related to sabotage, fire prevention, and accident prevention into one unified approach for a particular factory, utility, or other entity. The result, if executed properly, would be a comprehensive plan followed assiduously by a well trained and loyal workforce.

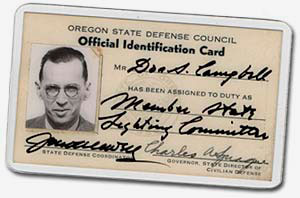

Photo identification cards were common in the defense industry. Many, such as this one for the Oregon State Defense Council, included fingerprints on the back side. (Folder 19, Box 34, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Photo identification cards were common in the defense industry. Many, such as this one for the Oregon State Defense Council, included fingerprints on the back side. (Folder 19, Box 34, Defense Council Records, OSA) The threat of sabotage and espionage resulting in damage to machinery, power stations, water supplies, and communication systems gave many civilian defense officials nightmares. They knew "the saboteur may be sly and furtive. He may strike when least expected, and attempts frequently to avoid suspicion by making his depredations appear to result from natural causes." In addition to saboteurs "throwing wrenches in the works," they worried about spies looking for improved production methods, specifications, plans, production rates and other sensitive information. They were on the lookout for suspicious characters who would infiltrate a factory or other strategic setting under the guise of being an employee, inspector, visitor, or some other authorized person. The key to battling these enemies was an educated and vigilant workforce. These ideal employees knew their fellow employees "intimately." They understood the dangers of talking business away from the workplace and of spreading unconfirmed rumors. And they were trained to understand the tactics of saboteurs and spies while remembering to avoid "suspicious" and "dubious characters."

Footnote

5

In order to tell the good guys from the bad, plant security required carefully investigating and identifying employees. While variations existed depending on the strategic sensitivity of the work site, background checks on employees often called for detailed personal histories of applicants, complete with interviews of past employers and personal references. Aliens required more thorough review and anyone making "doubtful statements" on the application warranted further scrutiny, possibly resulting in a report to the FBI. Fingerprinting was essential for employment at any facility that was vital to the war effort. Other plants participated voluntarily in the program. The goal was to turn up criminal records. However, considering chronic labor shortages, officials did not want to be too particular and therefore were "not primarily concerned with the morals of the employees, and disregard criminal records unless they disclose tendencies that make their employment a risk." Once employees were hired, they received a "tamperproof" badge that often included a photograph and fingerprints.

Footnote

6

Considering chronic labor shortages, officials did not want to be too particular and therefore they were "not primarily concerned with the morals of the employees, and disregard criminal records unless they disclose tendencies that make their employment a risk."

A good plant protection plan included other components. For example, air raid instructions were posted and employees underwent regular drills. Perimeter fencing was to be strong and in good order despite the fact that the "present metal shortages require the use of ingenuity in designing suitable fencing from available material." Entrances were to be kept to a minimum and either locked or guarded at all times. Local police, fire, and emergency medical services departments were to be made familiar with the plant conditions. Officials asked plant managers about their blackout plans and how long it took to achieve blackout after receiving the signal. Moreover, authorities pushed factory managers to create shelter areas within facilities along with plans for protection against a gas attack.

Footnote

7

Unlike shipyards and factories, which defended relatively discrete perimeters, railroads and utilities contended with hundreds of miles of track and line crisscrossing Oregon. While it was not possible to guard every mile of track or line, Federal civilian defense authorities made recommendations for components of rail and utility protection plans and the State Defense Council set up committees to work on implementing the plans around the state. Alert railroad maintenance crews and utility linemen on the lookout for anything out of the ordinary formed the best defense.

Southern Pacific Railroad employees train to be part of the company's Klamath Falls bomb protection squad. (Folder 23, Box 34, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Southern Pacific Railroad employees train to be part of the company's Klamath Falls bomb protection squad. (Folder 23, Box 34, Defense Council Records, OSA)

In addition to their regular work, these crews and other company employees trained in a variety of protection specialties. Some learned fire fighting, bomb reconnaissance and bomb extinguishing skills. Others trained in medical services and first aid. Not to be outdone by their husbands, in Klamath Falls the wives of Southern Pacific Railroad workers formed an auxiliary first aid committee of their own. And while railroad police already patrolled the railroad yards and lines, during the war officials stepped up the effort. The Klamath Falls railroad protection plan included an active defense police committee concerned with maintaining vigilance against possible saboteurs. The fear of this was highlighted by federal pressure on Governor Sprague to crack down on hobos catching rides on freight trains. Military authorities thought saboteurs might pose as hobos to gain access to railroads or forests for destructive purposes. (

see Hobo saboteurs?)

Footnote

8 Related Documents

"Plant Protection Check List,"

"Plant Protection Check List," California Oregon Power Company, Medford, U.S. Office of Civilian Defense, circa March, 1944. Folder 4, Box 18, Defense Council Records, OSA.

Notes