In Search of a Coordinated Response

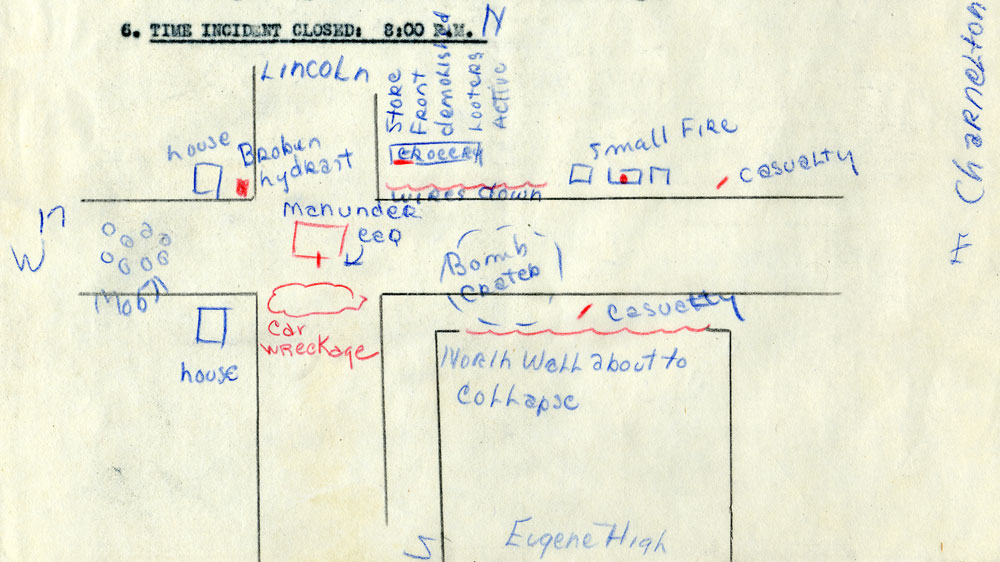

A diagram shows the aftermath of an imaginary bombing raid on West 17th Ave. and Lincoln St. in Eugene that was part of a training incident drill. (Folder 14, Box 18, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Enlarge image

A diagram shows the aftermath of an imaginary bombing raid on West 17th Ave. and Lincoln St. in Eugene that was part of a training incident drill. (Folder 14, Box 18, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Enlarge image

By 1942 authorities across Oregon had organized complex civilian protection programs staffed by tens of thousands of volunteers. But the work of these air raid wardens, auxiliary police and fire forces, fire guards, emergency medical teams, decontamination units, drivers, messengers, evacuation officers, public utility repair squads, and others (collectively known as the Citizens Defense Corps) had not

been tested in any meaningful way to see if it was well coordinated and integrated. To address this, the State Defense Council worked with county defense councils to develop and implement incident drills to put the system through its paces in communities throughout Oregon. The council also set up the first state control center in the nation to coordinate statewide activities in the case of a widespread emergency, such as an enemy attack.

Incident Drills

With the approval of the Army and State Defense Council authorities, local officials prepared elaborate incidents, some with the flavor of street theater, to test volunteers. Jackson County staged four nearly simultaneous incidents in December 1942. One bomb attack scene took place in the middle of Medford at the intersection of South Oakdale with 11th and J Streets. The "props" included an old car on its side to simulate a wreck, old lumber to simulate a fallen wall, rubbish for a fire on J Street, ropes and wires for fallen power and phone lines, lime to mark a bomb crater, a keg to play the part of an unexploded bomb, a hose to simulate a leaking water main, and smoke bombs as incendiary bombs. The players, one truck driver and 16 people to act as casualties, set up the incident ahead of time. The carnage was as follows:

Emergency crews arrived and swarmed over the incident scene while trained observers took careful notes on the performance on each group and the effort as a whole. Reports from included comments such as: "Tourniquet placed on left leg of patient at 7:25 (it was first placed on right leg but the patient called attention to the mistake)" and "Auxiliary police arrived at 7:59 but failed to keep the crowd in place and failed to control traffic." A Corvallis incident drill featuring a high explosive bomb and three wrecked houses in October 1942 exposed a dispatch error among other problems when the "ambulance did not arrive for casualties. No police were dispatched. Wardens performed no first aid. Address given in report did not conform to that given in written incident." Still, other comments heaped praise on the participants: "Some of the first aid rendered by these wardens reached a degree of perfection...."

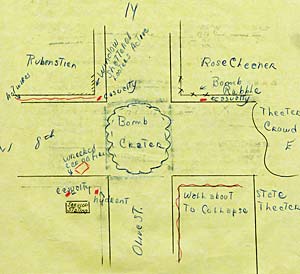

A bomb

crater, part of an incident drill,

sits in the middle of the intersection of West 8th Ave.

and Olive St.

in downtown Eugene. The diagram shows nearby businesses hit by looters and

a crowd in front of the State Theater. (Folder 14, Box 18, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Enlarge image

A bomb

crater, part of an incident drill,

sits in the middle of the intersection of West 8th Ave.

and Olive St.

in downtown Eugene. The diagram shows nearby businesses hit by looters and

a crowd in front of the State Theater. (Folder 14, Box 18, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Enlarge image

In addition to pointing out

cases of error or efficient response, observers also provided broader suggestions to help integrate the effort. For example, after one incident in Medford, observer George Field suggested that "air raid wardens become more inclined to assume [the] responsibility of their position and more thorough in their direction of the work to be done by the service when they arrive at the scene."

Footnote 2

Lane County officials came under fire after significant problems surfaced during a June 1942 incident drill in Eugene. Communication with the control center was the primary complaint. From 6

p.m. to 8:20 p.m. 65 calls got through to the control center, but 94 calls went unanswered because the line was busy. In one case an air raid warden had to wait 23 minutes to get a call through to the center. James Olson, assistant coordinator for the State Defense Council, put the deficiency in pointed terms: "The city of Eugene has an excellently planned and partially trained citizens' defense corps. Unless these various units can be integrated and dispatched through an adequate control center, the work done so far is largely wasted." Not to be outdone, Larry Duhrkoop, senior trainer for the State Defense Council, said that "the control center is perhaps the worst possible." Stung by the criticism, the Eugene City Council quickly passed a resolution approving more telephones for the control center to alleviate the bottleneck.

But the critics were not finished with the handling of the Eugene incident drill. They also pointed to the fact that reporters, apparently trying to make the incident drill as realistic as possible, set off a fire cracker right in the control center. Their intent was to "illustrate the possibility of a saboteur setting off a hand grenade." As observers noted, no one was hurt but if it had been the real thing "the entire control center would have been wiped out." Critics also pointed out that the reporters had not been asked for their identification before they were admitted to the control center even though "they might well have been alien enemies." Jack Hayes, in charge of civilian protection for the State Defense Council, distilled the Eugene incident drill down to its essence:

State Control Center

Officers of the Army's First and Fourth Fighter Command gather to inspect the new State Control Center in Salem. State Defense Council Coordinator Jerrold Owen in seated second from the right. (Folder 16, Box 11, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Officers of the Army's First and Fourth Fighter Command gather to inspect the new State Control Center in Salem. State Defense Council Coordinator Jerrold Owen in seated second from the right. (Folder 16, Box 11, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Even as State Defense Council officials castigated the performance of some local control centers, they had

to acknowledge that they did not even have a control center at the state level. Oregon officials broached the subject of creating one with the U.S. Office of Civilian Defense in the middle of 1942, asking the federal office for plans to set up a "central agency to serve the state in a capacity similar to the control centers of local defense councils." As Oregon State Defense Council coordinator Jerrold Owen recounted, the idea "was discouraged and [I was] rather curtly advised that the function of a state defense council was that of a planning agency solely, and it had no operative function in time of emergency."

Footnote 4

Undaunted, state officials forged ahead with "pioneering" what would be the first state control center in the nation. The goal was to set up a station where, during enemy attack, key state officials would gather to follow the progress of events and order the distribution of aid to local defense councils that requested it. Examples of help included fire fighting apparatus, blood plasma and other medical supplies, as well as food, clothing, or additional personnel. The control center would be staffed around the clock and would immediately notify the governor and other executive officials if the enemy attacked. Joining the governor in the control center would be the commander of the Oregon State Guard, superintendent of the Oregon State Police, state fire coordinator, state medical officer, state evacuation officer, state highway engineer, state public utilities commissioner, state adjutant general, state Red Cross director, and several others, including State Defense Council staff. Army liaison officers would also be present.

Footnote 5

Jack Hayes, State Defense Council Director of Civilian Protection, explains the operations of the new State Control Center to staff members. (Folder 25, Box 34, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Jack Hayes, State Defense Council Director of Civilian Protection, explains the operations of the new State Control Center to staff members. (Folder 25, Box 34, Defense Council Records, OSA)

In fact, despite the lack of support from federal civilian defense authorities, military officials were quite enthusiastic when approached for cooperation. They saw the center as a potentially valuable source of information about enemy movements and actions. According to military officials, in the event of an invasion, "civilians may come into possession of many valuable facts before they are reported to army intelligence. An army liaison officer at your control center can evaluate this information and pass on immediately that of military value." Proponents argued that the military intelligence could piece together such unrelated incidents as "the theft of an automobile later found abandoned in the vicinity of the Bonneville Power installations, the appearance of swarthy strangers in rural communities, the theft of dynamite from a logging camp, [and] the reporting of strange lights in a desolate waste," into a more sinister plot.

Footnote 6

Officials furnished the control center in Salem with communication and emergency equipment. One end of the center was lined with maps of the state and panel boards for plotting information about enemy movements. Batteries of telephones were staffed by "telephonists with headsets ready for action." In case of power failure, gasoline lanterns, flashlights, and candles were kept in stock. Officials also were ready with an alternate location for the control center in case the main center were bombed.

Once the State Control Center was up and running in May 1943 it participated with the military in a command post exercise involving the entire Oregon coastal area. To keep state officials on their toes, the military would provide no advance notice "except that 'D' Day would be within the next three weeks." Ten days later the exercise began. Within ten minutes key personnel arrived at the control center and 35 minutes later the "skull practice" attack moved forward. No actual personnel or equipment on the ground were used and officials, fearing an Orson Welles' "War of the Worlds" reaction, started and ended all communication with the word "drill." The attack included the bombing of military and industrial assets in Astoria, followed quickly by attacks on St. Helens, the Longview Bridge, the shipyards and bridges of Portland, and power plants at Bonneville Dam. Meanwhile, saboteurs destroyed a number of bridges near Oregon City.

Footnote 7

Telephonist Betty Barr receives an incident report while Defense Council Coordinator and State Control Center Commander Jerrold Owen reads a report. (Folder 16, Box 11, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Telephonist Betty Barr receives an incident report while Defense Council Coordinator and State Control Center Commander Jerrold Owen reads a report. (Folder 16, Box 11, Defense Council Records, OSA)

A "theoretical" Japanese plane dropped a bomb near the control center and disrupted all communication and power lines. While local fire fighters battled the flames, control center personnel kept working.

Responding to the crisis, the governor declared "theoretical" martial law, state highway workers blocked key highways to be used by the military, the Oregon State Guard patrolled the highways, fire pumpers were moved to stricken communities, and the mass evacuation of bombed communities was requested, which the military denied. Meanwhile, all of the lights went out in the state control center. Officials didn't miss a beat as workers grabbed the lanterns and flashlights to continue work: "Even the telephonist who was taking a message at the time of the unannounced blackout was not halted a moment but was able to continue writing the message being received, a flashlight in the hands of the Commander of the control center being beamed in her direction immediately [after] the lights were extinguished." Later, a "theoretical" Japanese plane dropped a bomb near the control center and disrupted all communication and power lines. While local fire fighters battled the flames, control center personnel kept working. All telephone messages were diverted to a State Police radio system and from there were relayed to a radio-equipped police car standing near the half-demolished building. A courier carried the messages from there to the control center.

Footnote 8

Jerrold Owen acknowledged that the theoretical attack was easier than a real one would be: "Had the flames been actual, the noise real, the danger acute, the operation would not have gone ahead so smoothly." Still, military officials, while making a number of suggestions, agreed that the control center was a success. They planned to recommend the control center plan to states throughout the West. And Owen summed up the experience: "Our first test naturally was not perfect and there are 'bugs' that we will endeavor to eliminate. However, as we started from 'scratch' with no specifications to follow, I feel that the first operation was quite successful."

Footnote 9

Related Documents

"Control Center Test"

"Control Center Test" Report, Oregon State Defense Council, May 21, 1943. Folder 16, Box 11, Defense Council Records, OSA.

Notes