Many Ways to Defend the State

Officials called the Civil Air Patrol the "Eyes of the Home Skies." Illustrated image courtesy Northwestern University Library

Officials called the Civil Air Patrol the "Eyes of the Home Skies." Illustrated image courtesy Northwestern University Library

In addition to the measures described in

previous chapters, Oregonians worked in other ways to secure the state from enemy attack. Some civilian protection programs, such as the Civil Air Patrol and the camouflaging of strategic facilities, did not develop as fully in Oregon as in

other states but still proved useful. Others, such as the civilian shore patrol, soon yielded to military patrol efforts. This page summarizes these programs and profiles two products from an inventor who pitched his fanciful designs for equipment to defend Oregon's coastline from attack.

Civil Air Patrol

In December 1941 the U.S. Office of Civilian Defense created the Civil Air Patrol (CAP) in response to the threat from submarines, primarily German U-boats that were causing significant damage to shipping along the Atlantic Coast. While Navy and Army aircraft took the lead in the hunt for submarines, the Civil Air Patrol made use of pilots who were overage or otherwise not eligible for the military. Some 40,000 volunteers flew their own planes on submarine patrol and missions such as transporting military passengers. After CAP pilots bombed 57 submarines, including several kills, the Army was so impressed that in 1943 it took over the program from civilian jurisdiction.

An entire fake town, complete with houses,

lawns, and trees covered Boeing Aircraft's Plant 2 in Seattle. The design was intended to camouflage the vital defense plant from enemy attack. (Image courtesy www.boeing.com)

Enlarge image

An entire fake town, complete with houses,

lawns, and trees covered Boeing Aircraft's Plant 2 in Seattle. The design was intended to camouflage the vital defense plant from enemy attack. (Image courtesy www.boeing.com)

Enlarge image

In Oregon over 1,400 volunteers enlisted in the Civil Air Patrol but military authorities maintained restrictions on submarine hunting off the Oregon coast. In spite of this, squadrons across the state in cities such as Astoria, Bend, Salem, Ontario and Portland stayed busy with ground training, drilling, courier services and other activities. For example, the Bend contingent undertook several tasks: "Although beset by bad weather and several minor accidents, the Courier service has made numerous round trip flights to Walla Walla since its inception." The group also responded quickly to help search for a missing Army bomber near Burns: "Within two hours after receipt of the request we had lined up three planes and six pilots to make the trip to Burns."

CAP newspaperFootnote 1

CAP newspaperFootnote 1

Camouflage Program

Plans to camouflage strategic facilities and operations in Oregon never really came to fruition. In the early days of the war, federal authorities anticipated the need to conceal vital assets from enemy bombers and in some states elaborate and ingenious camouflage of key defense factories was completed. For example, Seattle's sprawling Boeing Aircraft facilities, home to the B-17 "Flying Fortress" bombers, camouflaged nearly 26 acres of a plant. Workers covered Boeing's Plant 2 with a structure made of three-dimensional chicken-wire, plywood, and canvas. From the air, the resulting camouflage looked more like a town, with trees, houses, and schools, than an airplane factory.

In Oregon a state camouflage officer was appointed to work with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to study the problem and undertake

needed work. Each county in western Oregon also appointed a camouflage officer. Officials conducted a vigorous education program, with hundreds trained to be "camoufleurs." Still, the program never developed as hoped, leading Stanley Donogh, director of the Northwest Sector of the U.S. Office of Civilian Defense, to admit that "for some time I have feared that the camouflage program was bogged down." The program was "reorganized" to a lesser role by federal authorities in early 1943, prompting regrets from Donogh: "This puts us all in a rather bad light so far as our State councils are concerned. ...we went to considerable length to pursuade [sic] the Governor and his representatives that this was a program to which they should devote their best efforts." The work of the Camouflage Committee of the Oregon State Defense Council also soon ended "without there ever having been any actual camouflaging of installations in this state."

Footnote 2

Shore Patrol

Day and night patrols of the

Curry County coastline, such as here at Myers Creek Beach, led to frustrated

volunteers who pleaded to Gov.

Sprague for help.

(Enlarge image no. D7K-4217, Oregon Scenic Photos, OSA)

Day and night patrols of the

Curry County coastline, such as here at Myers Creek Beach, led to frustrated

volunteers who pleaded to Gov.

Sprague for help.

(Enlarge image no. D7K-4217, Oregon Scenic Photos, OSA)

The Oregon Shore Patrol was organized by American Legion posts in coastal counties in December 1941 at the request of the Army. The volunteers helped patrol many of the cold, rainy, and windy beaches 24-hours a day in the weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Later, increased Coast Guard coverage of the beaches reduced the need for these patrols. By April 1942 an Army general assured volunteers

"their services will not be called upon except in time of emergency and for very brief periods."

Complications sometimes occurred, however, as when the Army called on the Oregon Shore Patrol for help at 2:30 in the morning on April 5. Most volunteers got the word 13 hours later that the situation had passed and they

were "released" from patrol. Unfortunately, Curry County didn't receive the news. Days later a message came into the State Defense Council that "the boys down there were ready, willing and anxious to serve in any emergency but did not believe that they should be called upon to carry on a 24-hour beach patrol. Said they are still on the job down there since the call early Sunday morning last." Shore Patrol members in Port Orford were so frustrated by the long, dark hours of patrol that they fired off a resolution saying that "the American Legion and Citizens of Curry County, have maintained a vigilant Patrol, over a very extensive Coast Line to The California Border, Thru a Sparcely [sic] Populated Area, Necessitating extreme Sacrifice Of time and Money By all those participating in A Patriotic Service." The group asked Governor Sprague and Oregon U.S. Senator Charles McNary for "material and financial assistance" to help them. What they got instead was an apology along with assurances that it wouldn't happen again.

Footnote 3

The government encouraged inventors to submit their work. Poster image courtesy Northwestern University Library

The government encouraged inventors to submit their work. Poster image courtesy Northwestern University Library

Operation of the patrol shifted from the American Legion to the Oregon State Defense Council in the middle of 1942 but the program's days were numbered. As a result of improved Coast Guard patrols and Army installations along the Oregon coast, in January 1943 the commanding general of the Army's Northwest Sector directed that the Oregon Shore Patrol "be relieved of further responsibility" while expressing his appreciation for the "patriotic service of these veterans."

Footnote 4

Defense Inventions

The federal government opened science research and development offices that eventually led to major advances in atomic energy, radar, and synthetic rubber - all critical to the war effort.

Much of America's advantage in the war resulted from sheer production capacity, but inventions also gave U.S. forces an edge.

Recognizing this, the federal government opened science research and development offices that eventually led to major advances in atomic energy, radar, and synthetic rubber - all critical to the war effort. Some of these facilities, such as the atomic research center at Los Alamos, New Mexico, were vast and employed thousands. But the government also recognized the value of small amateur inventors tinkering at home in their garage or workshop. The U.S. Department of Commerce sought to tap into this resource by forming the National Inventors Council. The council encouraged inventors to send in their ideas. The council would evaluate the ideas and see that promising ones were studied further for possible production.

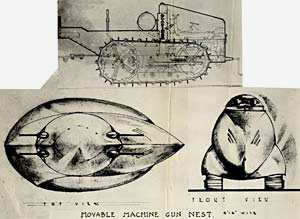

Some people, such as C. Stanley Bliss, combined their inventions with good old American entrepreneurial spirit. Bliss invented and marketed the designs for two defense related products to the military and Pacific Coast governors in 1943. The first he called the "movable machine gun nest." This was

an armor plated cover with four machine gun ports designed to fit over a small orchard tractor. Bliss contended these "small and very light" nests could be loaded on trucks and transported on

the coast highway at 60 miles per hour to the point of attack. Their mobility

would

thwart enemy artillery because the machine gun nests could be moved quickly "to avoid most any big gun attacks because it takes time to get the range." He designed the futuristic looking nest to be streamlined "with angles so rifle and machine gun bullets will glance off."

Footnote 5

An artist's conception of the movable machine gun nest. (Folder 6, Box 20, Military Dept. Records, OSA)

Enlarge image

An artist's conception of the movable machine gun nest. (Folder 6, Box 20, Military Dept. Records, OSA)

Enlarge image

To Bliss the best part of the nest for local home defense applications was

that it had a detachable armor covering: "the boys can be trained while doing farm work as a tractor, and upon the alarm being sounded, drive quickly into the shed and let down said armorplate, attach, and off you go to the point of attack."

Bliss wrote that each nest could be produced for Oregon for "the low cost" of $2,500, which was cheap considering that "no one can now say, after our present year's experience, just what the crazy Japs would not attempt."

Footnote 6

The second invention Bliss offered Governor Earl Snell was more ambitious. His "composite-type air ship" sought the best of all worlds: "Combine the four fundamental principles of flying..., the vertical lift of the helicopter, the surface and lifting power of airplane wings, the sustaining power of the dirigible, and the gliding and forward propulsion of the airplane...and you have the PERFECT FLYING MACHINE." It consisted of four long cylinders over a rigid framework. The cylinders contained "gas balloonets" that served to equalize the weight of the machine in air. This allowed it to be easily and accurately maneuvered using its propellers. Bliss envisioned numerous applications making the air ship infinitely more useful than "the old-fashioned Blimps" the government was building and stationing at Tillamook.

An artist's conception of the composite-type air ship. (Folder 6, Box 20, Military Dept. Records, OSA) Enlarge image

An artist's conception of the composite-type air ship. (Folder 6, Box 20, Military Dept. Records, OSA) Enlarge image

Military uses included "stationing one about every 500 miles between our Coast as the base of operations and the enemy wherever we wish to carry out a bombing attack. This mother ship could refuel our bombers in this way so as to extend their zone of operations...." The ship could

be stationed "so far out from shore that we would have ample time to send our fighting planes out to meet the enemy before they would be able to drop their bombs on our cities." Bliss also contended the air ship could fly so high that it could drop bombs on the enemy while being "invulnerable" to anti-aircraft guns and fighter planes: "In this way it can pack a wollup [sic] on the enemy without risk to its own hide." Each air ship would cost the people of Oregon about

$250,000.

Footnote 7

Blimps at the Tillamook Naval Air Station. Despite his best efforts, Bliss was unable to replace blimps with his air ship designs. (Image courtesy www.potb.org)

Blimps at the Tillamook Naval Air Station. Despite his best efforts, Bliss was unable to replace blimps with his air ship designs. (Image courtesy www.potb.org)

Bliss worked hard to gain Governor Snell's support for the inventions. While he might have hoped

Snell would approve the purchase of a few of the relatively affordable machine gun nests, realistically he could not have expected a small state to pay the fortune required to produce the air ship. Instead, Bliss apparently wanted the support of Pacific Coast governors to pressure the military to look seriously at his product designs. He claimed that military and "Government Engineers" "have stated that it definitely has military value" yet no orders had come his way. Bliss wanted to use governors as leverage and believed that "if the State takes action for defense of the Coast, the National Government will extend the same method up and down the coast in other states." Reminding the governor that he could "use his executive power and the treasury of the State for Home Defense," Bliss offered to visit Snell "so that 'Red Tape' may be cut and so that we can start manufacturing at the earliest possible moment." No evidence exists that Governor Snell or the Oregon Military Department responded to his offers.

Footnote 8

Meanwhile, the Navy erected two of the largest wood-frame buildings in the world at the Tillamook Naval Air Station as homes for eight blimps that comprised Squadron ZP-33. The 251-foot-long dirigibles moved out of these massive hangars and glided up and down the coast to patrol for enemy ships and submarines, often carrying depth charges to drop on enemy submarines. The blimps had a range of 2,300 miles at speeds of up to 40-50 knots. They could be stocked to keep a ten-member crew aloft for up to three days.

Related Document

Notes