Civilian Defense? "It's Your Job!"

"Ladies and gentlemen we are living in a new world. ...civilian defense is not the job of the army, the navy, or the police force. It's your job." So spoke Robert Smith of the Oregon State Defense Council in April 1942 on a KGW radio show entitled "Before the Bombers Come." Each week the 30 minute show hosted experts who covered civilian defense topics such as where to go and what to do in case of an air raid. There was plenty to learn.

Learning the Lesson

Defense council staff promoted the importance of air raid wardens to civilian defense plans. (Folder 15, Box 37, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Defense council staff promoted the importance of air raid wardens to civilian defense plans. (Folder 15, Box 37, Defense Council Records, OSA)

As with the Aircraft Warning Service, military and civilian defense officials learned a great deal about how to organize and train for air raids from the British. German air raids over London in 1940 killed and injured thousands and left large areas of the city in ruins. Facing ongoing attacks, the British responded by teaching citizens how to cope with fires from incendiary bombs and how to take shelter. While the raids continued, loss of life was greatly limited. Oregon officials played sound clips of a London raid to try to impress the potential horror to radio listeners with the added comment: "These are the sounds of a hell that I hope we in the United States will never experience."

Yet, the capability of the Japanese to strike Oregon was real, according to experts: "Just because we haven't yet received a visit from the Japs doesn't assure us that it can't or won't 'happen here.' The Japs have planes that can easily make the round trip to Portland with a full load of bombs, from their bases in the Aleutian Islands." And, the target was tempting: " We have important military objectives in Portland - our shipyards that are turning out ships that are supplying our forces in the fighting areas all over the Pacific theater."

Footnote

1 Moreover, officials reminded citizens of the 1942 words of Japanese leader Hideki Tojo: "The Japanese airforce is now ready to attack the American mainland...the people of America won't think it is so amusing when we bomb their skyscrapers."

Footnote

2Air Raid Instructions Issued

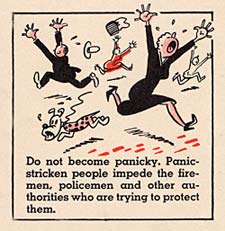

Officials feared that chaos during an air raid would limit the effectiveness of their response. (Folder 2, Box 34, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Officials feared that chaos during an air raid would limit the effectiveness of their response. (Folder 2, Box 34, Defense Council Records, OSA) In response to the ominous threat, officials issued instructions on what to do in case of an air raid. First, they emphasized that the alarm did not necessarily mean a raid was imminent, only that it was possible. The warning signal was a series of short blasts lasting about two minutes. The "all clear" signal was a steady blast of about two minutes. Upon hearing the alarm, regulations said that traffic should stop and people should seek shelter. If they were not near a designated air raid shelter, they were to find the nearest "handy" cover. Motorists were warned that they should drive to the curb and park without blocking intersections or bridges. Only emergency vehicles were allowed to move during an air raid event. People attending churches, theaters, and other public gatherings were to remain there and receive emergency instructions. People at home were instructed to get the family together in the safest room of the house away from windows or outside walls and turn off all gas and electric burners. They were admonished to stay off the telephone since the phone lines were needed for emergency workers. Instead, they were to listen to their local radio station for emergency information. At night during an air raid event, citizens were required to turn off all lights showing from the outside within one minute.

Footnote

3

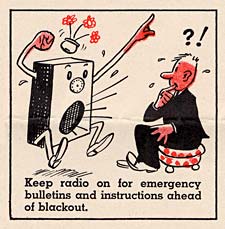

Civilian defense authorities warned citizens to stay off the telephone during an air raid and listen to the radio instead for emergency information. (Folder 2, Box 34, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Civilian defense authorities warned citizens to stay off the telephone during an air raid and listen to the radio instead for emergency information. (Folder 2, Box 34, Defense Council Records, OSA) Schools had similar air raid instructions. In many cases, the principal functioned as the air raid warden for the school and oversaw the regular practice drills that became familiar to students and teachers. Students would be ushered to an "air raid refuge" away from windows and doors. Often, these consisted of large interior halls or cellars with ample access points. Anticipating the obvious, principals were reminded that any refuge should have "easy access to drinking water and toilet facilities."

Footnote

4 In the competition for air raid services, Eugene school officials wanted school employees to be clear about which emergency obligations came first: "All teachers and janitors who have other defense assignments, such as air raid wardens, police or fire reserves, which would require them to go to some other place in case of a red alert, should arrange to be relieved from that assignment as soon as possible, so that they may be available for duty within the school at any time of emergency."

Footnote

5 Air Raid Wardens

Air raid wardens carried the preparedness message and education to most city blocks and communities in the state. About 8,000 men and women volunteered, attended warden schools, and put in long hours to help protect the state in the event of an attack. They brought what they learned back to their neighborhoods where they played the role of teacher, coach, inspector and commander. State officials offered high praise for the air raid wardens:

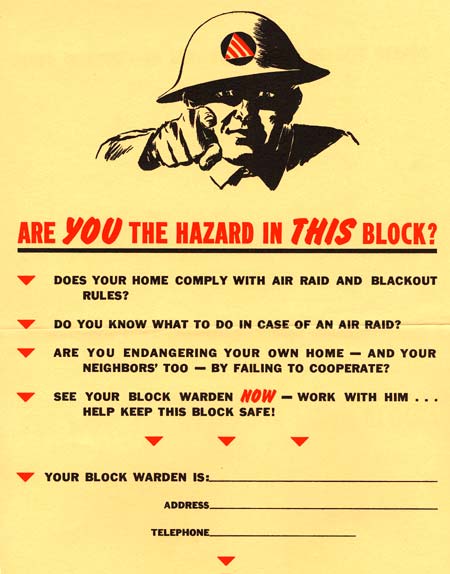

The system worked on the concept of collective responsibility for the protection of the block and the neighborhood, and a weak link in the chain could be disastrous. Citizens were reminded of their duty to assist and cooperate with the air raid warden. They also had a responsibility to prepare their homes for the possibility of a bombing: "You will not protect it with alibis and good thoughts. If your neighbor takes no interest in this program he has become a hazard to you."

Footnote

7

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, G. C. Waller of the Signal Oil Company in Albany offered the use of this loudspeaker equipped panel truck to the Oregon State Defense Council for emergencies such as air raids. (Folder 4, Box 19, Defense Council Records, OSA)

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, G. C. Waller of the Signal Oil Company in Albany offered the use of this loudspeaker equipped panel truck to the Oregon State Defense Council for emergencies such as air raids. (Folder 4, Box 19, Defense Council Records, OSA)

"Are you the hazard in this block?" People who failed to cooperate with the air raid warden endangered their own home and their neighbors' too. (Folder 2, Box 34, Defense Council Records, OSA) Enlarge image

"Are you the hazard in this block?" People who failed to cooperate with the air raid warden endangered their own home and their neighbors' too. (Folder 2, Box 34, Defense Council Records, OSA) Enlarge image In response to a question of what makes a good air raid warden, Ernest Brewer, director of the Oregon American Legion Air Raid Warden Training Program, responded: "You would have to know in your sector or block: everyone, every house, every street, lamp-post, manhole, gas shut-off, and electric connection."

Footnote

8 Citizens were encouraged to get to know their air raid warden who was described as being a sworn public official who would "have the ANSWERS to ALL QUESTIONS." Literature reinforced the air raid warden's "duty to survey every home on his or her block -- know each member of the family, know the location of blackout rooms, gas and electric shut-off switches, etc."

Footnote

9

Compliance with these lofty goals of air raid preparation and training varied. Some air raid wardens failed to contact their neighbors, let alone train them or inspect homes for hazards or safety equipment. One official lamented that "we have many people calling the defense office to ask who their wardens are. They tell us that no warden has ever contacted them; that they have no instructions." Some air raid wardens gave excuses about working long hours in war industries and being "too tired when I get home" to go into their neighborhoods to spread information or inspect houses. For these excuses officials offered a standard reply about a soldier in the Solomon Islands, a fierce Pacific Ocean battlefield, "who stands in gore and blood fighting...he too, is tired, but he fights on and his conscience is clear because he is doing his duty." In contrast, the air raid warden who failed to do his duty earned swift condemnation in the eyes of some: "It's Sabotage - That's What It Is. It's Sabotage!"

Footnote

10Related Documents

"What to Do in an Air Raid"

"What to Do in an Air Raid" Bulletin, Multnomah County Defense Council, circa June 1942. Folder 2, Box 34, Defense Council Records, OSA.

"Before the Bombers Come," KGW Radio Program Transcript, April 6, 1942. Folder 18, Box 31, Defense Council Records, OSA.

"Before the Bombers Come," KGW Radio Program Transcript, April 6, 1942. Folder 18, Box 31, Defense Council Records, OSA.

"Citizens Alert,"

"Citizens Alert," Radio Program Transcript, circa June 1942. Page 2, Folder 19, Box 31, Defense Council Records, OSA.

Notes