Preparing for the Worst

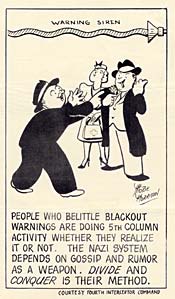

Authorities worked hard to see that people took the blackout warnings seriously. (Folder 2, Box 34, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Authorities worked hard to see that people took the blackout warnings seriously. (Folder 2, Box 34, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Officials saw blackouts and dimouts as essential defensive measures against the threat of Japanese air raids. Blackouts, which attempted to extinguish or shield light sources completely, usually were called for a relatively short period in relation to a possible imminent air raid. Dimouts, on the other hand, were primarily a regular, less restrictive measure taken in all or part of 14 western Oregon counties. Both measures caused their share of problems, particularly the dimouts, as Oregonians grappled with labyrinthine regulations, confusing interpretations, and new terms such as "foot candles" of light.

Blackout Drills Deemed "A Pronounced Success"

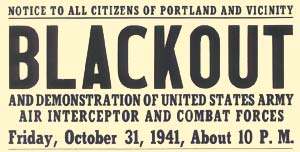

After months of preparation, Oregon civilian defense officials participated in a set of coordinated air raid maneuvers on Oct. 31, 1941. Designed to test numerous aspects of communication and organization, the maneuvers also tested the public's willingness to participate in a blackout during this pre-Pearl Harbor exercise. Army air interceptor and combat forces were scheduled to provide a demonstration in conjunction with the civilian defense program but most flights were scrubbed at the last minute because of weather concerns.

Officials posted notices across Portland and other cities announcing the blackout exercise. (Folder 6, Box 20, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Officials posted notices across Portland and other cities announcing the blackout exercise. (Folder 6, Box 20, Defense Council Records, OSA)

The numbers of volunteers participating were impressive. Multnomah County alone counted 8,000 "lady air raid wardens" and 10,000 male wardens along with over 1,000 auxiliary firemen and over 1,000 boy scouts. Lane County reported over 400 air raid wardens, 742 aircraft observers, and hundreds of associated participants during the blackout exercise. Other counties put up large numbers of participants as well, with the exception of several smaller eastern Oregon counties that reported incomplete organization.

Most reports of the maneuvers from county officials to the State Defense Council described the process as "very satisfactory" or "a pronounced success." Albany, for example, "was black and infractions of the rules were rare. It is true, of course, that a few minor errors took place. Such as, one or two sawmill open sawdust fires that, as you know, are difficult to extinguish and the lighting of matches and cigarette lighters. Business houses, industrial plants, automobiles, etc. came to a darkened stand-still. Even our largest industrial plant, the Albany Plylock Division of the M & M Woodworking Company, pulled all switches and smothered the boilers (to prevent smoke from the stacks) while several hundred men stood in total darkness."

Footnote 1

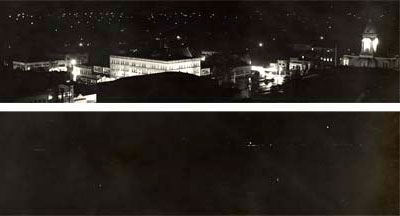

The upper photograph shows Salem before a blackout exercise on Oct. 31, 1941. The lower photograph shows the same view during the blackout. (Photographs, Defense Council Records, OSA)

The upper photograph shows Salem before a blackout exercise on Oct. 31, 1941. The lower photograph shows the same view during the blackout. (Photographs, Defense Council Records, OSA)

At the time of the maneuvers, Multnomah County lacked the funds for a dedicated system of sirens to signal the start of the blackout. Instead, officials drafted existing sirens into service: all fire stations drove their fire apparatus outside of the station and sounded their sirens along with the traffic sirens in front of fire stations. All city, county, and state police sirens in the area, all ambulance company sirens, all public, private, and parochial school sirens, and certain large factory sirens also sounded. Women fanned out across Portland's vast residential areas to patrol each block, "notifying occupants and giving instructions how to operate during the blackout." In the week prior to the blackout, the fire marshal sent inspectors to all of the theaters, beauty shops, sawmills, factories, warehouses and other sites in the area with instructions. The night of the blackout inspectors were assigned to theaters and places of public assembly. Boy scouts served as messengers, guarded fire boxes, and patrolled as air raid precautionary officers.

Blackout reportFootnote 2

Blackout reportFootnote 2

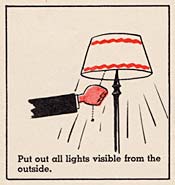

Blackout regulations required "lights out" if they could be seen from outside. (Folder 2, Box 34, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Blackout regulations required "lights out" if they could be seen from outside. (Folder 2, Box 34, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Other counties reported good results as well. Washington County "got a rating of 100%" yet still had a few problems: "We received five reports of 'Smart Alecs' who either did not turn off automobile headlights, or drove through the police lines with lights off." Officials also reported lights left on at a doctor's office, a grange, a machinery barn, numerous residences, and "several others of the careless [and] forgetful type." In Tillamook County the sirens sounded and "all lights seemed to go out instantaneously with the exception of the lights at the Football Game." Shortly after the lights were put out but not before "there was a terrible uproar from the crowds in the streets" about it.

Footnote 3

Halloween Fears Unfounded

A.L. Mason of Mason's Appliance Store in Tigard worried that his "place of business had to be darkened on that night when pure malicious conduct has taken the place of what was at one time just a little fun."

Problems associated with the maneuvers falling on Halloween were on the minds of some observers in Oregon. A.L. Mason of Mason's Appliance Store in Tigard worried to Jerrold Owen of the State Defense Council ahead of time that his "place of business had to be darkened on that night when pure malicious conduct has taken the place of what was at one time just a little fun." Owen passed the blame for the timing on to the Army Air Corps but also said that "the opportunity for unusual mischief is much exaggerated. If we have the kind of demonstration from the planes which we hope for, with flares dropping and bombers and pursuit ships overhead during the black-out the kids will be much too interested in what is going on in the air to take advantage of the temporary darkness." County officials expressed great disappointment that weather curtailed the planned aerial activity; one even complained that the Army pilots should have been better trained to fly in bad weather. But, despite the lack of flying distractions during the ten-minute blackouts, fears of widespread Halloween mischief failed to materialize.

Footnote 4

Blackouts Follow Pearl Harbor

Western Oregon also fell under a blackout on December 8 after the Pearl Harbor raid raised fears of an attack on the mainland. In Portland the blackout was far from complete, but

The Oregonian noted: "What the city lacked, however, in its first real war-condition blackout, was more than made up by the vigor of air raid precautions wardens, who worked furiously at the task of darkening the city." Many of Portland's streets were dark well before the 11 p.m. blackout. Early evening crowds quickly dwindled and "the lights of Broadway, far-famed for their brilliance, were snuffed out as by a giant hand." Meanwhile, air raid wardens "searched for light switches, pounded on doors, invaded hotels, and ordered the few automobiles remaining on the streets with unshielded headlights to the curbs." The neon signs and store display window lights still on in downtown caused a ruckus as "what remained of the street crowds gathered at these spots, angrily demanding that the lights be doused by rocks or any means."

Footnote 5

Poultry and Dairy Farmers Miffed

"It is a favorite practice of fifth columnists...to leave lights on in isolated farm dwelling[s] in a pattern which might point to a military objective, a guide to planes flying overhead."

Some people, particularly in rural areas, chaffed at blackout regulations since they were so far removed from military targets. Poultry and dairy farmers complained to the State Defense Council. Military orders after Pearl Harbor set up general precautionary blackouts dictating that no lights could show outside of poultry houses or dairy barns from 1:30 a.m. to 7 a.m. in much of western Oregon. But poultry and dairy cattle were "largely creatures of habit and by upsetting their routine will cause their production to fall off materially." John Stimpson of Locust Hatchery and Poultry Farms in Scappoose claimed he knew from experience "that hens will drop their egg production from peak production to a bare minimum by cutting out lights and disturbing their routine and it takes a period of from three to six weeks after disturbance to bring them back to normalcy." Jerrold Owen of the State Defense Council replied that he was "powerless to change the Army orders" and that he sympathized with the farmers. However, he noted that "it is a favorite practice of fifth columnists...to leave lights on in isolated farm dwelling[s] in a pattern which might point to a military objective, a guide to planes flying overhead."

Stimpson's letterFootnote 6

Stimpson's letterFootnote 6

More Practice Needed

People hung drapes or blinds over windows to comply with blackout rules. (Oversize Records, Defense Council Records, OSA)

People hung drapes or blinds over windows to comply with blackout rules. (Oversize Records, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Oregon civilian defense officials expressed frustration after the Army banned practice blackouts in the wake of the Pearl Harbor attack. According to Jerrold Owen, "it has, of course, been absolutely impossible for civilian defense agencies to perfect blackout arrangements and to make certain that communities and areas can be blacked out promptly when no practices or tests are permitted."

Owen made several requests to the Army to lift the ban and at least one general gave him a "sympathetic ear." Still, military officials remained concerned about whether "defense councils are prepared to handle the traffic problems adequately."

Footnote 7

Eventually in 1944, the Western Defense Command allowed applications for some limited five-minute practice or test blackouts. These were restricted to one every three months and were to occur only on Sundays between 9:30 p.m. and midnight.

Footnote 8

Related Document

Notes