"The Word 'Bomb' Sounds Unpleasant"

Oregonians watched news reels of the bombing of London and other devastated targets and wondered "could that really happen here?" Authorities answered with an emphatic "yes" and prepared the state for the worst. This included organizing tens of thousands of Oregonians who volunteered for the Aircraft Warning Service and served as air raid wardens. But to be effective every citizen needed to be ready to respond to a variety of terrible weapons that could fall through their roof. It happened in Britain; it could happen here.

Authorities told people to get inside if bombing occurred. If that were impossible, they were to lie down and "protect the back of your head." (Folder 2, Box 34, Defense Council, OSA)

Authorities told people to get inside if bombing occurred. If that were impossible, they were to lie down and "protect the back of your head." (Folder 2, Box 34, Defense Council, OSA) State Defense Council Coordinator Jerrold Owen acknowledged his challenge in a 1942 radio broadcast as he encouraged Oregonians to learn more: "...first I'd like to say right now that because the word 'bomb' sounds unpleasant is no reason to turn off your radio at this point. The more you know about bombs, the less they scare you. So let's not avoid the subject because it's unpleasant. Bombs are far more dangerous to you before you know about them than after." Owen went on to describe the three general classes of bombs: demolition, incendiary, and gas.

Footnote

1 Demolition Bombs

To help citizens prepare for the worst, officials described the characteristics of demolition or explosive type bombs. Because of their weight, often from 100 to 500 pounds, and the height from which they would fall, the mere impact of this type of bomb could cause considerable damage. The extent of the damage from the explosion would depend on whether the bomb struck a building or fell out in the open. The huge pressure blast developed by the explosion was enough to flatten lightly constructed buildings. Great hazard also resulted from flying or falling debris, glass splinters, and bomb fragments.

While much of the danger came from pure bad luck - being in the wrong place at the wrong time, authorities also gave instructions for how to reduce loss of life and injuries if a demolition type bomb fell in the neighborhood. Citizens were advised to seek "substantial cover" in designated bomb shelters, if possible. If not, they were told go to their home's "refuge room" or "throw a mattress over a strong table and get under the table." People were also advised to stay away from windows and doors and lie down to avoid being knocked down by the concussion and to lessen exposure to bomb fragments, flying glass, and debris.

Footnote

2 And, they were cautioned to stay away from open areas such as streets or parks. In fact, as Governor Sprague noted in a radio interview, the British experience under the onslaught of German bombs taught a valuable lesson: "...it was found that a man within his own home, away from windows and outside walls, was ten times safer from injury than a man standing in the open."

Footnote

3

Women display two "bomb-fighting gadgets" that inventors dreamed up in case of air raids. The "traps" were designed to scoop up incendiary bombs. The one on the right is asbestos lined. They were not recommended by federal civilian defense officials. (Folder 16, Box 37, Defense Council, OSA)

Women display two "bomb-fighting gadgets" that inventors dreamed up in case of air raids. The "traps" were designed to scoop up incendiary bombs. The one on the right is asbestos lined. They were not recommended by federal civilian defense officials. (Folder 16, Box 37, Defense Council, OSA) Officials expressed great concern about the hazards of unexploded bombs (UXB) or "duds." While the bombs could have originated from enemy forces, such as with the Japanese balloon bombs, authorities were most worried about U.S. military ammunition "on terrain formerly used by the War Department for training troops or in areas where such training is going on."

Footnote

4 Several children were killed or injured in West Coast incidents leading Colonel Joe Leedom of the federal Office of Civilian Defense to note that "we all know the danger from a 'dud' and also know how the souvenir-hunting instinct of most of us might lead us to pick up some such object, if it be small enough to carry away."

Footnote

5 If an unexploded bomb were found, the local air raid warden was to cordon off an area of 50 yards and notify a control center that would dispatch a trained bomb reconnaissance agent to dispose of the bomb.

Incendiary Bombs

Incendiary or fire bombs struck the fears of Americans with particular force after the "all out" attack on London by German bombers in December 1940. As Governor Sprague described: "Incendiary bombs fell like rain and a fire of terrifying proportions consumed the entire district known as the old city of London. Hundreds were killed and the property loss ran into billions."

Footnote

6 Several types of incendiaries posed a threat, including phosphorus, thermite and magnesium bombs. Phosphorus bombs were in ways less dangerous because they burned at only about 250 degrees Fahrenheit. Thus, for a fire to start, the material around it had to be very combustible. Thermite bombs, in contrast, burned incredibly hot, up to about 4,500 degrees Fahrenheit, and could melt metal or rock. This was made clear to Oregonians when a thermite bomb was dropped in September 1942 by a Japanese plane on a forest in Curry County. The resulting crater showed signs of intense heat, including fused earth and rocks that resembled lava. Sand and water were recommended to extinguish phosphorus and thermite fires.

In a demonstration, a woman pumps water from a pail while a man prepares to spray water on an incendiary bomb. (Folder 12, Box 35, Defense Council, OSA)

In a demonstration, a woman pumps water from a pail while a man prepares to spray water on an incendiary bomb. (Folder 12, Box 35, Defense Council, OSA)

According to Portland Mayor Earl Riley who also served as director of the Portland and Multnomah County Civilian Defense Council, magnesium bombs were the most widely used incendiary devices at the time "and the one which can and must be controlled by the civilian population."

Footnote

7 The two pound bombs were about two inches in diameter and about nine to 14 inches long with a steel fin. Inside the cylinder was the incendiary material and a firing fuse to be set off by a sudden shock. Once burning, the magnesium could get as hot as 3,300 degrees Fahrenheit.

An air raid warden instruction booklet set the scene of a magnesium bomb attack: "Picture a large bomber carrying 2000 of these bombs, flying at 5000 feet and at a rate of 250 miles per hour. The bombs will be dropped in lots of about 20 each second. They will scatter over a length of some seven miles. The width of this path has been observed to be some 150 yards." That equated to about 20 bombs falling on each city block over a huge area. The drop of a bomb from the plane developed enough force to penetrate the average house roof, allowing magnesium to start burning in the attic or top story. As the bomb casing caught fire, it would throw molten metal over a wide area, up to 30 to 50 feet. The bomb would burn with high intensity for up to two minutes and more quietly for up to 15 minutes. Air raid wardens, it seems, had their work cut out for them.

Footnote

8

Portland defense coordinator Edward Boatwright put the situation in practical perspective:

"There just isn't any fire department in the world that can be in a thousand places at one time. But incendiary bombs only start small fires and if the people can put out 990 of the 1000 fires while they're still little ones the fire department can take care of the ten that aren't caught in time and have become big fires."Footnote

9

To help homeowners fight those 990 smaller fires, the Portland and Multnomah County Defense Council distributed the following instructions to residents:

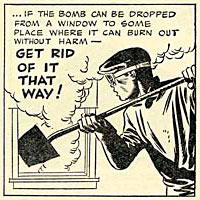

Get rid of that bomb! (Image source: Folder 16, Box 37, Defense Council Records, OSA)

METHOD NO. 1

Get rid of that bomb! (Image source: Folder 16, Box 37, Defense Council Records, OSA)

METHOD NO. 1EQUIPMENT: Garden hose attached to a water supply and equipped with an adjustable spray nozzle, or some form of force pump that will throw a stream of water, such as a pump tank, spray pump, or stirrup or bucket pump equipped with 20 feet of hose and an adjustable spray nozzle.Incendiary bomb cartoon

PROCEDURE: Approach the bomb in a prone position shielding face and hands with whatever is available and play a steady SPRAY of water on the bomb. Keep surrounding furniture, carpets, etc., wet. If fire starts in these, switch to a solid stream and knock down the fire, then switch back and SPRAY the bomb until it burns out.

METHOD NO. 2

EQUIPMENT: 2 loosely filled bags of DRY sand (20 to 30 pounds), 1 bucket containing 3 inches of DRY sand and 1 additional bucket full of DRY sand; 1 long handled shovel, 1 garden rake and a hatchet, axe or hand axe.

PROCEDURE: Wait until the initial shower of sparks has subsided (requires from 30 to 60 seconds), then approach the bomb with a sack of sand or bucket of sand. Place the sack on the bomb or pour the sand over the bomb from the bucket. Then with the rake, pull the bomb and sand onto shovel and toss out the window. Or place the bomb in the bucket containing 3 inches of sand, cover the bomb with sand and dump outside. Wet gloves are good protection for the hands. Dark glasses should be worn if available.

Footnote

10

Air raid wardens were instrumental in training citizens on the block for how to fight the fires and an important aspect of this was to keep flammable clutter in homes to a minimum, especially in the attic. This could take diplomacy as many wardens learned: "It takes a most exceptional person to be able to tell a housewife that the trash in her attic constitutes an air raid hazard, and to tell her in such a manner that she likes it."

Footnote

11 Gas Bombs

Though they had been used in Ethiopia and China, authorities saw attacks coming in the form of poisonous chemical gases as less likely than those involving explosive or incendiary bombs. Yet they still planned for the possibility and tried to educate the public on the types of gas as well as protection and response measures. Part of the education was to remind citizens of the events of World War I as Chemistry Professor Thomas Thompson did in 1942: "Modern chemical warfare came into being on April 22, 1915, with a surprise attack at Ypres [Belgium] when the Germans on a four-mile front discharged 168 tons of chlorine gas. Within half an hour the Allies suffered 15,000 casualties, including 5,000 dead; with proper protection casualties would have been almost nil."

Footnote

12 Effective gas masks and training lowered casualties from chemical gas attacks in World War I.

Use Your Sniff Kit!

One of the first steps in effectively combating a chemical warfare gas was to identify its presence. That was the idea behind the "Sniff Kit" produced and sold by the Northam Warren Corporation. The kit carried the recommendation of both the federal Office of Civilian Defense and the Chemical Warfare Service of the Army, which played a role in developing the product.

The kit consisted of imitations of the five main gases used in chemical warfare: mustard gas, phosgene gas, chloropicrin, lewisite, and tear gas. The 5 bottles came attractively packaged in a "case made of wood and pressboard, covered with serviceable quality of saddle tan fabric." Each bottle carried a label with the physiological effect of the active gas along with first aid steps and neutralization methods. The kit sold for five dollars.

The kit consisted of imitations of the five main gases used in chemical warfare: mustard gas, phosgene gas, chloropicrin, lewisite, and tear gas. The 5 bottles came attractively packaged in a "case made of wood and pressboard, covered with serviceable quality of saddle tan fabric." Each bottle carried a label with the physiological effect of the active gas along with first aid steps and neutralization methods. The kit sold for five dollars.

Oregon officials made good use of the kits in their training. The federal government thought so much of them that they set up a program to distribute the kits free to accredited gas warfare instructors.Footnote

17

Experts classified gases by the length of time they remained on a target. Chlorine and phosgene were more prominent examples of non-persistent gases. These would linger for only a short time and could be carried away by air currents in less than 15 minutes. Persistent gases, such as mustard gas and lewisite, were actually liquids, often dispersed in mist form, that evaporated over a period of days and could be absorbed by cloth, leather, wood or other materials.

Some gases caused damage by irritating the lungs. Chlorine, a yellowish-green gas with a pungent odor, was an example of one that experts thought could be used in an attack. The first aid for this gas was limited: "Keep patient quiet and warm by wrapping in blankets. Hospitalize immediately." Phosgene, another lung irritant was colorless and had an odor of "musty hay or decaying leaves." In smaller concentrations, experts recommended a cigarette test to warn of its presence since the phosgene would give the smoke a "somewhat disgusting metallic taste." First aid for phosgene was limited as well, consisting of not allowing any exertion and keeping the patient quiet and warm. If the exposure to lung irritant gases was of a long duration, permanent lung damage and death were possible. Pneumonia often set in as a complication.

Footnote

13

Mustard gas and lewisite were examples of blistering gases. Mustard gas smelled like garlic or horseradish and took the form of a dark liquid that could penetrate skin and clothing. The first aid emphasized the need to remove it within 3 minutes of contact by blotting the area with solvent soaked gauze. Mustard gas exposure could cause blisters and severe inflammation but no internal poisoning. Lewisite was more dangerous. The oily dark liquid had the odor of geraniums and acted like mustard gas. But the burns resulting from exposure could go through the skin and into the muscle leaving the victim badly scarred and often blind. First aid called for rinsing of the eyes quickly: "Delay may mean blindness." Skin was to be swabbed quickly with a strong solution of hydrogen peroxide or bleach.

Footnote

14

Along with educating the public about the dangers of gas attacks, State Defense Council officials wanted to hand out free gas masks to nearly every Oregon resident. In January 1942, the council coordinator, Jerrold Owen, explained that Congress had passed a bill to supply 50 million masks to people within the "target areas" that included most of Oregon. Owen predicted that "every resident of those areas would be required to carry a gas mask at all times."

Footnote

15 In the end other priorities overtook the drive to put a gas mask on the hip of every Oregonian. After the war federal officials went to some effort to collect the approximately 15,000 training gas masks that it had distributed through the Oregon State Defense Council in 1942, but no mention was made of the effort to distribute masks on a massive scale.

Related Documents

"The Unexploded Bomb"

"The Unexploded Bomb" Bulletin, Oregon State Defense Council, circa 1942. Folder 19, Box 31, Defense Council Records, OSA.

Notes