Blowing Off Steam Can be Good for the Cause

Getting enough recreation was as important as getting plenty of sleep and good food to maintain the energy needed to stay productive. Drawing of factory worker image courtesy Northwestern University Library

Getting enough recreation was as important as getting plenty of sleep and good food to maintain the energy needed to stay productive. Drawing of factory worker image courtesy Northwestern University Library

"Recreation is a hard-boiled necessity in these times, an investment in our Number One asset - human resources." This statement from the Federal Security Agency recognized the stress brought by war, even on the home front. Civilian defense industry workers toiled in high intensity, quota driven

and sometimes dangerous settings; they frequently lived in overcrowded housing; and many commuted long distances to work extended schedules, often swing or graveyard shifts. On top of this, they were bombarded with pressure from the government, civic groups, and

neighbors to volunteer as aircraft ground observers, war bond workers, or

other worthy jobs. Many who failed to volunteer were labeled unpatriotic. On the military side, tens of thousands of men and women in the armed forces were either stationed in Oregon or passed through the state and needed to "blow off steam" on a regular basis. Moreover, officials were battling rising rates of what could be called the four horsemen of the home front: prostitution, venereal disease, gambling, and juvenile delinquency. In response, government agencies, along with other organizations, put together

recreational offerings in an effort to keep morale high and hold "un-social" activities at bay.

Footnote 1

Problems in Home Front Life

Officials recognized the stress carried by many workers who were new to the

highly mechanized factory settings prevalent in defense industries. Many

employees at factories had migrated from the hard working but more organically paced life of the farm,

to find themselves in the middle of a war production line: "machines whirring, spinning; electric hammers pounding; pulleys moving and giant cranes swinging; tools cutting, punching, polishing to the thousandth of an inch - life and death hanging upon the turn of a hand." Not surprisingly, many workers were "still shy of the monstrous machines, the roar of noise, the Vulcan fires of the furnace."

Footnote 2

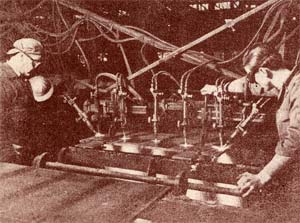

These employees of a Portland area shipyard were part of a civilian army of workers. Many had difficulty adapting to the fast-paced mechanized world of defense industries. ("Record Breakers" Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation Promotional Booklet, Oregon State Library Holdings)

These employees of a Portland area shipyard were part of a civilian army of workers. Many had difficulty adapting to the fast-paced mechanized world of defense industries. ("Record Breakers" Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation Promotional Booklet, Oregon State Library Holdings)

Authorities also noted that life didn't stop at the plant gates. Instead, another type of stress dogged many people after they laid down their tools for the day

and started their commute home. A large number of workers left their lifelong support networks, such as families, churches, and civic organizations, hundreds or thousands of miles away when they migrated to take defense jobs. Living in a strange city, not knowing the neighbors, dealing with shortages, and countless other problems led to excessive drinking, marital strain, and other manifestations of alienation.

Workers needed more than wages and patriotism, as a Federal Security Agency publication stated: "They must have some chance to be human beings, have places to go in time off, to entertain and to be entertained, to dance or

enjoy themselves according to their age and taste." Of course, those tastes could vary widely as in two examples: "Uncle Joe, 60, when he leaves the drill press, may like to sit in the shade of a tree with his pipe, and whittle. Jinny, his granddaughter, 20, will chose the hilarity of juke-box dancing after a day's riveting, and why not?"

Footnote 3

There were strong production oriented reasons for encouraging tired workers to

join recreation programs. Injury and illness often followed tense and tired workers and the resulting statistics made a compelling case. One expert, Carl Brown, claimed in 1943 that "accidents and illnesses snatched 484,059,000 workdays away from the Nation's war-pressed industrial output in the year just ended." To make the numbers more understandable, he said the effect was "the same as though enemy bombers had knocked out

for the entire year 1,861 industrial plants, each employing 1,000 men and women...." Officials noted that armies of millwrights and other maintenance workers toiled in factories to keep the machines running at peak production, but the "maintenance of the human machine is more likely to be neglected."

Footnote 4

Mothers who worked in factories had to come home to care for children, prepare meals, and do chores, thus adding to stress. (Box 5 of 28, Education Dept. Records, OSA)

Mothers who worked in factories had to come home to care for children, prepare meals, and do chores, thus adding to stress. (Box 5 of 28, Education Dept. Records, OSA)

Women suffered problems that added to their stress since many

had "double jobs" and "it is hard to be both plane maker

and home maker." Many women, as with men moving from farm life, were new to the strains and pressures of the factory. After long work shifts, women often went home to shop for food, prepare meals, clean the house, look after children, and perform other chores. Among the tasks, they had to navigate the byzantine world of ration coupons and price ceilings while trying to volunteer in some way for the war effort. The resulting stress was very damaging according to experts who noted that "statistics show that women are ill more frequently than men; by the very nature of their physique they are more easily tired."

Footnote 5

Mobilizing to Attack the Problems

Government and local communities mobilized to attack these problems by forming committees, recruiting volunteers, and developing plans. Many communities were hampered by the huge influx of workers overtaxing meager recreational facilities. In other places, recreational opportunities were limited to a few hours in the evening, a problem noted by

officials: "The 9-to-5 work life is gone, three-shift schedules to which we have adapted demand three-shift community services." In Oregon the State Recreation

Committee, a subset of the Oregon State Defense Council, coordinated and acted as liaison between federal agencies and county and local recreation committees.

These entities showed incredible imagination and resourcefulness in tackling the need for recreation despite significant hurdles. Tire and gas rationing made car

travel to recreational destinations problematic, as did the government frowning on recreational travelers clogging up rail coaches needed for the war effort. Moreover, a large number of materials needed for constructing recreational facilities were either impossible to obtain or in short supply. Instead of these, many recreation committees would have to rely on creativity and baling wire.

Footnote 6

Officials were keen to survey the needs of a community so that efforts to usher limited resources could be most effective. For example, in 1944 a U.S. House committee investigating congested areas issued a report on the Columbia River area that pointed out recreational deficiencies in Portland. The investigators, citing a "lack of recreation leadership," said that among other things Portland needed a downtown industrial recreation center, recreational equipment such as tennis shoes and basketballs, and gymnasiums and sport pavilions in the Guild's Lake and Vanport housing projects. They also recommended a "colored recreation center and theater in Albina."

Footnote 7

Once communities had completed surveys, identified needs, and developed program plans, they were able to tap grant money from the federal Lanham Act pot, although competition was stiff for any significant amount of funding. In fact, apart from possible grant money, some state officials had little time for federal government help. In 1942 Walter May, chairman of the State Recreation Committee, encouraged local recreation committees to develop their own plans since he had a dim view of the work on the federal level: "If we let the recreation activities under State auspices take on too much of the color of la-de-dah, such as some of the bright young men at Washington seem to have in mind, we could easily be criticized in the face of so serious a situation."

Footnote 8

The cover of a 1943 manual

offering

suggestions for creating recreation programs.

(Folder 5, Box 31, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Enlarge image.

The cover of a 1943 manual

offering

suggestions for creating recreation programs.

(Folder 5, Box 31, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Enlarge image. Recreation in war time manual

Recreation in war time manual

Volunteers were needed to make any community recreation program successful and officials suggested that planners cast a wide net. Professional people were needed. These included accountants to keep the books; doctors to give physicals related to athletic recreation; landscape gardeners to lay out and maintain playgrounds and outdoor party settings; teachers to train volunteers; and writers to publicize the effort through the press, radio, posters, and pamphlets. Business people could raise money, get advertising space, and serve as typists and stenographers. Athletes could organize games and help with the training, coaching, and refereeing related to sports. Artists were sought to teach classes in music, painting, sculpture, stage production and design, arts and crafts, dancing and photography. Farmers could pitch in with Grange and 4-H Club programs by teaching how to care for animals or cultivate gardens and by leading fishing and hunting trips as well as square dances. Officials didn't want to leave out "volunteers who are experienced in home management but have no special recreational skill...." They were invited to supervise children at play centers, plan recreation for "shut-ins, the aged and sick," and serve as hostess or chaperone at social functions. They could also help by "welcoming to the community such newcomers as service men and defense workers and their families, offering them hospitality in their homes, meals, etc."

Footnote 9

Local Recreation Efforts

The possibilities for recreational facilities and activities were equally encyclopedic as evidenced by the efforts of communities across Oregon. The Portland area, with by far the largest concentration of population and defense industries in the state, led the way. Reporting to the Portland mayor, the Parks Bureau director of recreation claimed that managing a large recreation program "is a little like playing God; the director is dealing with the lives of men. Recreation is planned by hundreds, led by thousands, participated in by millions and directed by a few." He went on to speak about the "impressionistic canvas" of the recreational offerings:

"the flash of a batted ball, the splash of the swimmers, some figures that are children running in track meets, some sprawled and crumpled figure resting in the park, the lines of dancers, the theater goers, the music lovers in the open air."Footnote 10

Perhaps the recreation director could be forgiven for his indulgence

in reporting on his program considering the staggering numbers of

activities and participants described. The report claimed that from

Dec. 1, 1943 to Aug. 31, 1944 "a total of 4,386,974 persons partook

of recreational activities either as a participant or spectator." Of that total, about 1,500,000 participants divided

their time between a number of activities including 92,045 men's basketball players and nearly 3,500 "Goldenball" players. Upcoming plans included "radio skits,

comedies and farces and Saturday shows of every variety for the children" as well as "caravan troopers, the impromptu local talent shows; the string ensembles and dance bands."

Footnote 11

Tennis was one of many recreational pursuits promoted by civilian defense officials to help maintain healthy minds and bodies for the war effort. (Folder 2, Box 35, Defense Council, OSA)

Tennis was one of many recreational pursuits promoted by civilian defense officials to help maintain healthy minds and bodies for the war effort. (Folder 2, Box 35, Defense Council, OSA)

The summer period of June 1 to August 31 drew nearly three million participants and spectators as the report detailed, including 7,804 participants in zoo trips. The Portland Circus brought in an audience of 12,500 while the Vanport Circus counted 5,000 people. The circus parade in downtown Portland had over 500 participants and 17,000 spectators. More than 400 performers in the "Hanzel & Grethel" pageant drew over 8,000 in the audience while "caravan shows" pulled in nearly 13,000 people and tennis court dances attracted almost 10,000 people. The Multnomah County Sheriff Band gave eight concerts totaling 360 performers

and 5,650 in the audience. More than 33,000 people took in the "Fourth of July Physical Fitness demonstrations" while special dances and swimming parties put on by the Russian Merchant Marines tallied 1,100 people. Baseball and softball put up big numbers. The Portland Baseball Association included 26 adult teams and 32 junior teams that contributed to over 175,000 players and fans. The Portland Softball Association was even bigger. It included 42 industrial league teams with over 600 players. Kaiser shipyards fielded 24 teams with 360 players. All told, nearly 500,000 people were associated with the softball program. Over 61,000 players

flocked to Portland's city-owned golf courses.

Other programs pulled in smaller numbers but were entertaining nonetheless. The "Story Hour Lady" had 9,241 listeners over the summer while lawn bowlers numbered 542 and educational tours drew nearly 2,000.

Footnote 12

State and local recreation committees focused

on providing wholesome outlets for the servicemen at military facilities across Oregon. Shown above are barracks at Camp White near Medford in 1943. (Image courtesy Camp White Museum)

State and local recreation committees focused

on providing wholesome outlets for the servicemen at military facilities across Oregon. Shown above are barracks at Camp White near Medford in 1943. (Image courtesy Camp White Museum)

Other communities around the state developed programs

on a smaller scale. Astoria volunteers "sponsored an entertainment in the form of

a midget troupe of professional actors." Civilians were charged admission but servicemen got in

free. A service club in Eugene formed a "gang buster" organization to program "wholesome" pursuits for the younger boys in an effort to reduce juvenile delinquency. The recreation committee in Bend asked the local school board to employ two physical education teachers on a year round basis to help develop and organize a civilian recreation program. And, Stanfield recreation officials targeted a trailer camp with 70 units as deserving of recreational help while Pendleton volunteers hoped to build an

"outside roller rink." to entertain locals and servicemen.

Footnote 13

Recreation for Service Men and Women

Oregon towns and cities faced problems finding recreational outlets for men and women serving in the military who were stationed at various large and small facilities around the state. Hermiston had a large ordnance depot; the Corvallis area played host to Camp Adair; the Portland area provided recreational opportunities for various military facilities, including the Vancouver Barracks; Camp White was in the Medford area; Pendleton had an air base; Astoria had Fort Stevens and the Tongue Point Naval Air Base; other coastal communities played host to several Coast Guard operations and to the blimps at the Tillamook Naval Air Station. And several other Oregon communities had a military presence or impact of one sort or another, including Albany, Redmond, Salem, Bend, Madras, Klamath Falls, The Dalles

and Ashland. While the federal government would chip in money, it expected local communities and organizations such as the United Service Organizations (USO) to pull the load of providing recreation to members of the armed forces. Once again, Lanham Act money played a big role in funding programs.

The State Recreation Committee had definite goals in relation to those in the armed services. Speaking on a radio program in 1942, one committee member described its aims:

"The State Recreation program contemplates nothing that will lend to 'soften' the men in the active fighting force. It will make it its business, however, to hold down to a minimum the activities of the vicious influences in the community. It will, give every assistance to local committees who want to provide something for the men in service to do besides walk the streets."Footnote 14

The attractions of Portland's "big city" life drew

servicemen seeking recreation. Many

came from military facilities in the area such as the Vancouver Barracks while others were passing through on their way to assignment or furlough. Shown above is the corner of Front and Alder streets in 1941.

(Photo no. 1456, Highway Dept. Records, OSA)

Enlarge image

The attractions of Portland's "big city" life drew

servicemen seeking recreation. Many

came from military facilities in the area such as the Vancouver Barracks while others were passing through on their way to assignment or furlough. Shown above is the corner of Front and Alder streets in 1941.

(Photo no. 1456, Highway Dept. Records, OSA)

Enlarge image

Portland's city life was

a strong attraction to servicemen on leave and officials wanted to guide them away from the easy to find houses of prostitution and gambling and to more wholesome entertainment. Numerous centers, houses, clubs, and canteens, run by organizations such as the USO, Red Cross, Salvation Army, and others, fit the bill. For example, the George A. White Service Men's Center on 3rd Avenue offered free beds, showers, shaves, and snack bar food along with a library, music room, game room, daily dances, and even free legal advice. The YMCA-USO Center on 6th Avenue featured chapel singing, coffee and doughnuts, swimming, dancing, and services such as pressing, mending, shopping

and wrapping. The Jewish Community Center on 13th Avenue had swimming, basketball, weightlifting, boxing, steam rooms, and a lounge with a "junior hostess group" sponsoring parties on the weekends. The Chinese Service Center on 3rd Avenue had ping pong, games, a piano, and Chinese and English language newspapers and magazines. The Williams Avenue USO center offered showers, entertainment, food, and letter writing to black servicemen, which was fortunate because "public eating places for Negro workers and service men are extremely limited throughout the State" according to the State Recreation Committee.

Footnote 15

Hundreds of thousands of service men and women traveled through the state on their way to new assignments and recreation officials catered many programs for them. One offering was the Troops in Transit Lounge on the main floor of Portland's Union Station train depot. The room was outfitted with tables and benches, while "subsequent gifts of venetian blinds, modern lighting fixtures, leather chairs, and a phonograph have given the room a more inviting atmosphere. Flowers provide a bright and cheerful note." The center served all branches of the service and "included officers and enlisted men, both white and Negroes." The lounge saw significant growth during its first year beginning in 1942, climbing from 972 guests in its first six weeks to over 10,000 visitors in its last six weeks. This rise caused a corresponding need for more volunteers, who by 1943 numbered "7 day captains, 7 co-captains, 58 regular hostesses, and 40 substitute hostesses."

Footnote 16

Portland’s Williams Avenue USO center offered showers, entertainment, food, and letter writing to black servicemen, which was fortunate because "public eating places for Negro workers and service men are extremely limited throughout the State.”

Other Oregon communities offered recreational outlets as well. The recreation committee in Albany helped solve an overnight housing problem for servicemen by using facilities at the old Albany College buildings. Both the City of Corvallis and Oregon State College "sanctioned the use of their facilities for service men use." The local recreation committee also planned to build shelters on the highway at nearby Camp Adair and in Corvallis for use by servicemen waiting for the bus. Cannon Beach offered a "commercial skating rink" while Grants Pass operated a "hostess league which has organized girl hostesses who participate in dances at Camp White." Hermiston, which ballooned from a town of 700 to 11,000 in just a few months, had a significant USO presence. Independence volunteers put on "various parties during the week for soldier entertainment which includes games, cards and dances" along with "a fruit basket which is always full." Pendleton showed movies and put on dances. Moreover, "a Negro service men's Center was opened the latter part of May [1943] and is operated by a representative of the U.S.O. Negro division." In Salem, 190 private homes opened their doors to help with an overnight housing problem for servicemen.

Local officials also ran a "fine hostess league" that provided dance partners for events at Camp Adair and in Salem.

Footnote 17 (

Listen to Jo Stafford sing "I Left My Heart at the Stage Door Canteen"

Listen to Jo Stafford sing "I Left My Heart at the Stage Door Canteen" - via youtube.com)

Related Documents

"Recreation In War Time"

"Recreation In War Time" Manual, U.S. Office of Civilian Defense, May 1943. Folder 5, Box 31, Defense Council Records, OSA.

Notes