"While We Do Not Discriminate, We Do Segregate"

African Americans faced continuing discrimination and segregation during World War II. At the same time, a number of developments during the war served to quicken the pace of the struggle for equal rights. The massive migration of African Americans from the rural South to cities in the North and West brought new opportunities and challenges. Jobs in the military and defense industries brought expanded horizons and increased expectations. And, the hypocrisy of America fighting for freedom in other lands while denying it to minorities at home brought new legitimacy and resonance.

National Developments

African American civil rights groups and institutions grew in number and militancy during the war, determined to use the war effort to extract concessions and make gains for the movement. Many African American civil rights leaders vowed not to repeat what they saw as the mistake during World War I of putting aside their grievances for the duration of the war. One outgrowth of this strategy was

the "Double V" [Victory] campaign, which aimed to fight racist fascism at home and abroad at the same time: "Defeat Hitler, Mussolini, and Hirohito," one newspaper exhorted, by "Abolishing Jim Crow." The campaign called on Blacks to loyally serve the nation while emphasizing the contradictions between America's professed values and its

behavior with respect to racial discrimination.

Footnote 1

A. Phillip Randolph, honored in a 1989 postage stamp, worked tirelessly during the war for civil rights. (Image courtesy alphabetilately.com)

A. Phillip Randolph, honored in a 1989 postage stamp, worked tirelessly during the war for civil rights. (Image courtesy alphabetilately.com)

One African American leader, A. Phillip Randolph, used the threat

of a

large scale protest march on Washington to push President Roosevelt to issue Executive Order 8802 in 1941. The order declared that "there shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in the defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origin." Roosevelt also established the Fair

Employment Practices Commission (FEPC) to receive and investigate related discrimination complaints. But the commission had no real enforcement power and was relegated to using publicity and moral persuasion to bring about change. Still, while progress came slowly, more and more African Americans found work in shipyards and factories during the war and the creation of FEPC set the first precedent of action by the federal government on behalf of Black rights since 1875.

Footnote 2 (

Listen to Josh White sing "Defense Factory Blues" about discrimination in the defense factories

Listen to Josh White sing "Defense Factory Blues" about discrimination in the defense factories - via youtube.com)

Other efforts were made to increase opportunity and reduce segregation in the military but key leaders such as General George C. Marshall feared desegregation would weaken morale while Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson simply considered African Americans to be inferior, writing in his diary: "Leadership is not embedded in the negro race yet." However, some gains were made with a 1941 policy that African American strength in the Army would reflect its percentage in the population (about 9%) and that African American combat

and noncombat units would be formed in every branch of the service, including the formerly all-white Army Air Corps and Marines. Still, the units would remain segregated and Black servicemen suffered widespread discrimination throughout the war, often relegated to noncombat duties, subjected to racial quotas, and excluded from military career opportunities available to whites.

Footnote 3 (

Listen to Josh White sing "Uncle Sam Says" about discrimination in the military

Listen to Josh White sing "Uncle Sam Says" about discrimination in the military - via youtube.com)

Riots in Detroit in June 1943 killed 9 whites and 25 African Americans. This violence, along with riots in other cities, exposed the racial tension that developed as large numbers of Blacks moved from the rural South to urban centers. (Image courtesy The Detroit News)

Riots in Detroit in June 1943 killed 9 whites and 25 African Americans. This violence, along with riots in other cities, exposed the racial tension that developed as large numbers of Blacks moved from the rural South to urban centers. (Image courtesy The Detroit News)

By the summer of 1943, rising African American expectations triggered in part by

relatively high paying defense jobs collided with growing resentment on the part of many working class whites to bring about the worst race riots in the country since the bloody aftermath of World War I. The riots hit communities such as Springfield, Massachusetts and El Paso, Texas, but the worst violence was in Detroit, Michigan. While the causes were many, much of the friction resulted from chronic overcrowding in housing, transportation, and recreation facilities. For example, most of the African Americans in Detroit were crowded into a 60-block slum, ironically called "Pleasant Valley," where sewage ran in the streets and residents seethed with frustration. Racial fistfights in June triggered 36 hours of mayhem during which stores were looted and mobs attacked and counterattacked. By the time federal troops restored a shaky peace, nine whites and 25 African Americans were dead. The specter of race riots continued to worry city police forces across the country for the remainder of the war.

Footnote 4

Housing in the Portland Area

Aerial view of a portion of the massive Vanport housing project. Many housing projects in the Portland area segregated residents by race. Image courtesy City of Portland Archives and Records Center

Aerial view of a portion of the massive Vanport housing project. Many housing projects in the Portland area segregated residents by race. Image courtesy City of Portland Archives and Records Center

Oregon, in particular the Portland area, experienced many of the general demographic changes brought about by World War II. Nationally, shipyard and factory jobs drew hundreds of thousands of African Americans from the rural South to large cities across the country as industry leaders scrambled to fill war production orders. At the same time millions of men were leaving the labor force to enter the armed forces. The growth of the Black population in Portland echoed this trend, skyrocketing from under 2,000 before the war to over 22,000 in 1944. Combined with the concurrent rise in the number of working class whites in the area, the steep total population increase of about 160,000 led to inevitable overcrowding and friction. As a result, existing prejudices grew more pronounced as more African Americans looked for housing, jobs, and access to hotels, restaurants, and other services.

Footnote 5

Housing was an ongoing problem for newly arriving African American migrants to the Portland area. Many found temporary shelter at local churches or in Black-owned businesses but eventually needed to find permanent housing. The completion of the massive Vanport housing project, together with other projects open to Blacks in Guild's Lake, Linnton, Fairview, and East Vanport, as well as several in the Vancouver area, helped ease the crunch. But discrimination came with the package as a Portland Council of Churches report noted in 1945:

African Americans seeking apartments away from the projects encountered similar attitudes. The Portland Council of Churches reported there were "few apartments in the city available to Negroes." Those few that were offered for rent to Blacks were small two to four room units owned by African Americans. Representatives of the Apartment House

Owners' Association said they had no policy prohibiting renting apartments to Blacks but they claimed they had received no applications from Blacks and they "agreed that Negro occupants would not be welcomed unless in a segregated project."

Footnote 7

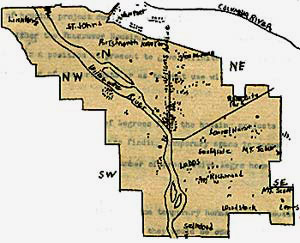

Dots on a map of Portland show the distribution of African American population and businesses. The majority of Blacks were restricted to the Williams Avenue corridor running north-south in the middle of the city. (Folder 3, Box 3, Gov. Snell Records, OSA)

Enlarge map image

Dots on a map of Portland show the distribution of African American population and businesses. The majority of Blacks were restricted to the Williams Avenue corridor running north-south in the middle of the city. (Folder 3, Box 3, Gov. Snell Records, OSA)

Enlarge map image

Blacks attempting to buy housing in the Portland area ran into the same roadblocks in the form of policies and covenants found in other communities across the country. One report found "a general policy among mortgage firms that only 50% of the appraised value of a Negro's home shall be financed. Thus, with inflated real estate prices, the Negro finds it more difficult to buy a home." This policy combined with other collective actions to further limit where African Americans could purchase property. A 1945 Portland City Club report noted

that interviews with representatives of the Portland Realty Board along with prominent area Realtors disclosed "a policy of restricted sale of property to Negroes. Such restriction confines the sale of any member of the Realty Board to Negroes to the segregated area (bounded by N.E. Holladay, North Russell, North Williams and the Willamette River), with limited sale in Woodlawn, Alberta, and Waverly Heights...." The policy was part of the local board's code of ethics which declared that a Realtor should never do anything, including selling to "any race..., whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values in that neighborhood." This policy applied even if "the owner instructs him to sell to anyone."

Footnote 8

Employment in the Portland Area

Discrimination in employment persisted through World War II for African Americans

and other minorities. Prior to the war, many Blacks found jobs as hotel and

train waiters and porters along with a handful of other unskilled positions. During the war, limits to the range of jobs open to African Americans remained in place. As one report noted, the position of the employer "in most instances has been guided by what he feels is an adverse attitude of his employees or the public who patronize his place of business." Thus, Blacks generally were excluded from jobs in cafes and restaurants. Some worked in hotels, such as the "full staff of Negro bus boys" that one hotel had recently hired in 1945. But many Portland hotels used more workers of Filipino descent than Blacks. Department stores resisted hiring African American employees in jobs other than as maids and janitors, citing the general feeling that "the hiring of qualified Negroes in jobs other than of a service nature would not meet the approval of the public." White employees also provided resistance as a report noted:

"One department store employing Negro elevator operators recently dismissed these workers and hired white girls. There was no dissatisfaction with the service of the Negro girls. The general attitude of the employer...is that the white employees will refuse to work with Negro help."Footnote 9

During the war a large number of the African Americans in Portland held jobs in shipyards, factories, and construction sites, often working the graveyard or night shift. Unions, which played a big role in employment on these job sites, had a mixed record of discrimination. A 1945 survey of Portland labor unions examined policies related to admitting Black members. Of the 14 unions contacted, eight admitted African Americans as full members. Six unions excluded Blacks although two of these had "Negro auxiliary unions." For example, the Building Worker's Union, Local 296 had 2,000 Black members out of about 5,500 total members. According to the survey, "it is claimed that there are no interracial problems in the union, and it was stated that some of the best workers are Negroes. No educational program was felt necessary."

An African American welder works on a liberty ship. Blacks suffered discrimination by many labor unions during the war. Library of Congress, image no. fsa 8b04228

An African American welder works on a liberty ship. Blacks suffered discrimination by many labor unions during the war. Library of Congress, image no. fsa 8b04228

Likewise, the Electrical Worker's Union had nearly 1,000 Black members out of a total of 8,000. The union representative stated that "within the union, everyone has equal rights." He did note that several years earlier there were one or two instances in which white workers refused to work with African American members. In these cases, the Black members were kept on the job and the white workers "went to another job or quit the union." The Carpenters' Local 583 spokesman said that union cards were issued to Black members in "the regular manner" but voiced the common observation that "their experience has been that frequently after they have sent a Negro out to work, the contractor soon sends him off the job."

Footnote 10

Several unions excluded African American members. The local International Woodworkers of America kept them out despite the international union's policy of non-discrimination. A union local spokesman said Blacks were "kept out by the prejudices of the men who refuse to work with them." The Laundry Workers' Union 107 held a similarly sour view on admitting Blacks as members, saying that "Negro workers had been tried, but other members demanded segregation. As no facilities for segregation were available, they were let out." The union representative went on to say that "the colored workers were not interested in union activities, in improving working conditions, and their work was not up to standard." The local Boilermakers' Union had no Black members but an auxiliary lodge was set up in Vancouver. Their representative gave several comments that the survey report summarized:

The Negroes are not excluded because of "maliciousness" or prejudice on the part of the Whites, but because there is less trouble and things run more smoothly when they are separate. The Negroes do not work as well or accomplish as much under Negro foremen or bosses as they do under White bosses. You can deal easily with the educated or talented Negro, but can't get anywhere with the mass of uneducated ones.

Footnote 11

Other Discrimination in the Portland Area

Racial discrimination showed up in other aspects of life in the Portland area, but results were not consistent, with some institutions relatively free of overt measures. For example, two separate reports on race relations in the Portland area in 1945 concurred that

public schools "drew no barriers on the basis of race." One report

stated that "in the high schools in the city, you will find mixed youth working together more or less successfully." The report also noted that there were no

restrictions on extra-curricular activities and high school clubs. Another report stated most colleges and universities accepted Blacks without discrimination, although a few imposed

housing restrictions. Most hospitals got good grades as well, albeit with some caveats. For example, the Vanport Hospital stood out for segregating patients and several local hospitals limited nurses' training for African Americans. County health institutions treated all patients equally. Meanwhile, convalescent homes practiced almost complete segregation. In fact, only two would grudgingly admit Blacks, which caused "an acute problem with aged and infirm Negroes."

Footnote 12

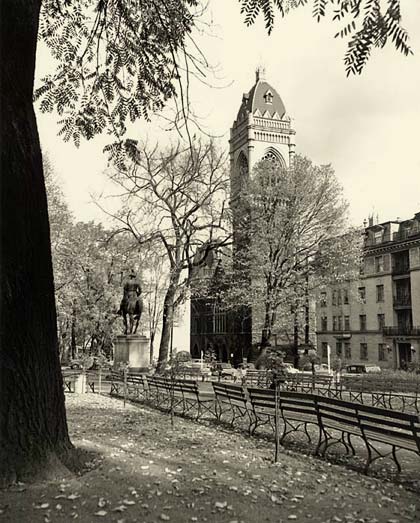

Churches received mixed reviews in a 1945 survey of racial discrimination. Shown above is the the Congregational Church on the South Park Blocks in downtown Portland. The church was known for its progressive views on racial issues. (Photo no. 3213, Highway Dept. Records, OSA)

Enlarge image

Churches received mixed reviews in a 1945 survey of racial discrimination. Shown above is the the Congregational Church on the South Park Blocks in downtown Portland. The church was known for its progressive views on racial issues. (Photo no. 3213, Highway Dept. Records, OSA)

Enlarge image

Churches received mixed reviews in the survey of racial discrimination. Some of the problem may have come down to the subtleties between theoretical statements and

actual behaviors when it came time to welcome a Black family over the threshold of the church. The survey noted that "the announced policy of churches of all faiths and denominations in Portland permits Negro worship" but blamed church governing boards for any opposition to African American membership. Some of these leaders voiced views such as "'Christian worship should be segregated. God intended it so. It is expedient since Negroes feel more at ease in their own presence. God has cast the color line, and expects it to be respected." Yet other church leaders expressed very different attitudes: "Segregation is not the answer. All should work together. Segregation, prejudice, is a refraction on the intelligence of people." According to one report, Portland had about six churches with multi-racial membership.

Footnote 13

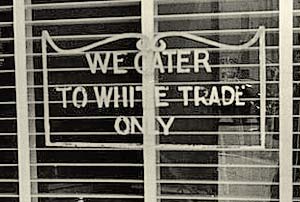

African Americans seeking to eat in Portland restaurants were sometimes met by signs telling them they were not welcome. (Image courtesy Library of Congress)

African Americans seeking to eat in Portland restaurants were sometimes met by signs telling them they were not welcome. (Image courtesy Library of Congress)

Restaurants and hotels generally were singled out for their poor record on

racial issues. According to reports, "a few of the higher class restaurants and cafes refuse service to Negroes while a much higher percentage of the smaller restaurants

and cafes refuse service." Many of the smaller lunchrooms and restaurants, especially in the areas of Portland frequented by "working men" displayed signs reading "'White Trade Only.'" One report noted that "visiting race relations authorities have pointed out that Portland is the only city on the [West] Coast where such signs are displayed." Most restaurants wouldn't "specifically ask Negroes to

leave or otherwise draw public attention to this policy, but such instances have occurred." Some Black diners experienced discrimination by other minorities. According to

The Oregonian newspaper, one African American went into a Chinese restaurant in 1945 where a "Chinese girl" called his attention to a sign reading "We cater to whites only." The diner promptly inquired: "How the hell did you get in here?" As a further variation of practice, some restaurants would serve African Americans only if they were with white diners.

Footnote 14

Blacks suffered similar indignities in Portland hotels where only one was known to

admit Blacks without restrictions. A report added that "one other hotel will accept noted Negro guests, although it has been reported that this hotel restricts the hotel privileges of the Negro guest. Other hotels generally refuse to admit Negro guests under any circumstances." On a more positive note, with one exception, theaters and concert halls did

not discriminate. The exception was one theater that was "located on the fringe of the largest Negro neighborhood and follows a policy of requiring Negroes to sit in the balcony."

Footnote 15

Related Documents

"Compiled Report,"

"Compiled Report," Commission on Race Relations of the Portland Council of Churches, 1945. Folder 3, Box 3, Gov. Snell Records, OSA.

Notes