Left: Boys who worked 300 hours in farming for the U.S. Boys' Working Reserve earned this bronze service badge; Right: All boys enrolled in the reserve received this button; Bottom: Boys who worked full time all summer earned this service bar. (OSA, Oregon Defense Council Records, Publications and Ephemera, Box 9, Folder 2)

Left: Boys who worked 300 hours in farming for the U.S. Boys' Working Reserve earned this bronze service badge; Right: All boys enrolled in the reserve received this button; Bottom: Boys who worked full time all summer earned this service bar. (OSA, Oregon Defense Council Records, Publications and Ephemera, Box 9, Folder 2)

One young wag in Klamath Falls offered the following observation: "The 'grown ups' of Klamath County have been congratulated many times on the manner in which they contributed to every drive, benefit and entertainment but it is the boys and girls who urge them on. The young people come home to preach the gospel of patriotism and the older ones carry it out. However, the young ones do not stop at preaching but also practice."

Throughout Oregon, children proved these words to be true as a number of organizations formed, or adapted, to include them in the war effort. Some of these targeted a specific gender, such as the United States Boys' Working Reserve. Others, such as the Junior Red Cross, engaged both boys and girls in productive work.

"Making Boy Power Count"

War brought chronic food shortages to the U.S. America's demand, coupled with the need to double exports to desperate European allies, led to calls for greatly increased production. But at the same time, the U.S. suffered an ongoing labor shortage. In an attempt to solve both problems at once, the U.S. Department of Labor organized the United States Boys' Working Reserve in May 1917. The goal was to enroll hundreds of thousands of 16 to 20 year old boys to work primarily on farms during summer vacation, thus boosting production and easing the labor shortage. Much of the remainder of 1917 was spent building an organization in each of the states in cooperation with the state councils of defense.

Enrolling Members

Local libraries and high schools were targeted as conduits for enrolling members. The National Program of Library Cooperation asked local libraries to distribute literature and applications to "all boy patrons" and compile a list of all reserve age boys. The librarian was asked to be on the lookout for boys who did not attend school so they could be recruited into the reserve. Likewise, high school principals were asked to steer boys into the program. In some states, school holiday and spring vacations were shortened in order to add weeks to the summer working season. And schools made provisions in the fall to help boys catch up with studies in the event that farm duties ran past the beginning of the school year.

View enrollment card. (PDF)

Uniform of the U.S. Boys' Working Reserve. (OSA, Oregon Defense Council Records, State Historian's Correspondence, Box 1, Folder 45) View catalog. (PDF)

Uniform of the U.S. Boys' Working Reserve. (OSA, Oregon Defense Council Records, State Historian's Correspondence, Box 1, Folder 45) View catalog. (PDF)

All physically fit boys were eligible. The reserve noted that participation was entirely voluntary. But, as with other war work, obligation played a role: "It is the duty of every boy to file for membership immediately; it is the sterner duty of every parent to see that his boy is enrolled." Pressure was put on county directors and enrolling officers to get every boy signed up: "MAKE YOUR DISTRICT 100%." In Oregon enrollment began on April 1, 1918 and it fell short of expectations. The Oregon defense council cited a lack of time to enroll students before the end of the school year. Because of this, "there was not much effort made to organize and place boys residing outside the City of Portland...." Still, over 13,000 boys were enrolled in Portland.

Upon enrollment, each boy was required to pass a physical examination and provide an oath of service. He would then receive his enrollment button and certificate. Moreover, he was "then privileged to put on the military National Reserve uniform, with the arm chevron." The reserve "hoped" each boy would buy a uniform. But it recognized that the cost of up to $10 could be too much for some families, and therefore made it optional. Boys who met certain criteria were eligible later to receive and wear special service badges.

Training for Farm Life

City boys often found themselves at a disadvantage when working on farms. Because of this, the reserve asked boys to study "Farm-Craft" lessons at their local school or library in the winter months to learn the "elements of farm practice." In the spring, the reserve organized a training camp at the Multnomah County Farm to provide basic hands-on instruction. About 150 boys attended the training provided by Oregon Agricultural College instructors.

Similar camps across the country used a system of drill and calisthenics so that the boys were "hardened and strengthened" for the work ahead. Another training method for city boys was described in "Boy Power" the monthly bulletin of the reserve: "They may be taken to the livery stables or a near-by farm and given lessons in harnessing and feeding horses, and the language of horse driving and care given to them."

Thirty Dollars and Board

Once enrolled and trained, the boys were assigned to farm camps or to live with a farm family. The reserve promoted the value of the new workers to employers: "...even though inexperienced, the strong, healthy boy, inspired by patriotism, is a capable and adaptable helper in the field or factory." But officials also were sensitive to concerns about child abuse and child labor laws. The reserve reminded employers that it "has been firm in upholding child labor laws and contending for reasonable hours of toil." While it recognized that farm hours were long and varied, 12 hours of work in a day seemed to mark the upper limits. Generally, boys were expected to work the equivalent of eight hours a day six days a week. Reserve officials were charged with actively supervising the working conditions as well as the "health and moral welfare" of the boys on farms and in the farm camps, backed, of course, by the full authority of the Department of Labor.

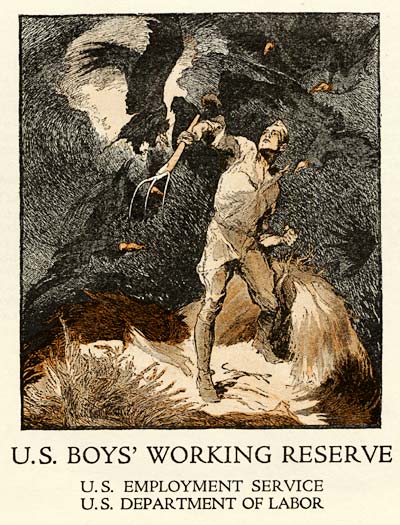

This booklet cover shows a heroic view of the work of the U.S. Boys' Working Reserve. (OSA, Oregon Defense Council Records, State Historian's Correspondence, Box 1, Folder 45)

This booklet cover shows a heroic view of the work of the U.S. Boys' Working Reserve. (OSA, Oregon Defense Council Records, State Historian's Correspondence, Box 1, Folder 45)

Many Portland boys were sent to one of 14 YMCA camps in the vicinity of berry fields and cherry orchards. They were to earn a minimum of about $30 per month plus board. For this sum, the boys together harvested over $21,000 worth of strawberries, loganberries, and cherries that season. The program was popular with farmers and fruit growers who were happy for any relief from the labor shortage.

A Continuing Need for the Reserve

With the signing of the Armistice in November 1918, the hostilities ended but food shortages in Europe were projected by Herbert Hoover to rise steeply as the former Central Powers nations of Germany, Austria, Bulgaria, and Turkey urgently needed help. Thus, reserve officials planned an even bigger effort for the U.S. in the next year: "Its production in 1919 must far surpass all previous records in every state in the Union if the world is truly to be 'made safe for democracy.'" Once again, "boy power" would be called on to fill the breech.

Boys Scouts

In addition to the U.S. Boys' Working Reserve, Oregon boys also had the option of helping the Boy Scouts of America in its war work. The scouts were busy according to the Portland Council's scout director: "We wish to say that the Portland Council, Boy Scouts of America, have been in every drive, every piece of patriotic work, and every piece of public service...in Portland." Over 1,200 boys helped with the work in Portland, sometimes forming over 100 groups per month. They ran errands, solicited funds, and participated in numerous drives. Scouts in Portland also distributed over 30,000 pamphlets on war information and spoke at various events.

The Junior Red Cross

The Red Cross was very active in Oregon schools where children could help produce needed items and be educated at the same time. Schools were enthusiastic about the partnership as the director of junior membership for the Northwestern Division of the Red Cross reported to the Oregon superintendent of public instruction in August 1918: " Almost universally I find that both teachers and pupils are eager for work- so eager, in fact, that it has been quite a difficult task at times to find things for them to make which are both useful and educational at the same time."

Indeed the children did stay active in a variety of ways for the cause. A report documenting the work of the Junior Red Cross in Oregon for the year ending June 1, 1918 noted just some of the typical accomplishments:

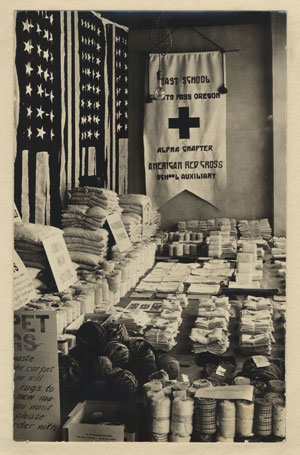

The Grants Pass Red Cross school auxiliaries showed off some of the war work of students in this display. (OSA, Oregon Defense Council Records, World War I Photographs)

The Grants Pass Red Cross school auxiliaries showed off some of the war work of students in this display. (OSA, Oregon Defense Council Records, World War I Photographs)

ASTORIA: Have gathered 2500 pounds of digitalis [medication made from the foxglove plant]. They are beginning to gather sphagnum moss [used as a surgical dressing]. The Juniors made 6000 surgical dressings.

HARNEY: Made 1000 Red Cross badges for Seniors.

JOSEPHINE: Helped the Seniors at sales. Sent in Red Cross song.

LA GRANDE: Made filing card boxes, paper holders, and sock stretchers for Chapter.

MORROW: Juniors took care of small children while Mothers went to Red Cross meetings. One shoulder shawl made of old woolen stockings by a teacher in Morrow County aroused a great deal of comment at the exhibit at Pittsburgh.

PORTLAND: Portland Juniors made and sent 144 pints of marmalade to Vancouver Barracks.

THE DALLES: Juniors distributed cards for Food Administration, ran errands, et cetera.

Participation was remarkable. Clatsop County alone accounted for 28 school auxiliaries with a total membership of 2718. By the end of the war, the county's Junior Red Cross had produced a large number of items designed to make life a little easier and more enjoyable for the men in military training camps and in combat. These included 1000 joke books, 100 bedside tables, 150 bedside bags, 460 property bags, 400 handkerchiefs, and 46 pillows. The chapter's children also had the distinction of gathering 80% of the foxglove used by the United States in the war. The children were active in other ways as well, buying large amounts of liberty bonds and war savings bonds, gathering used clothing for drives, running errands, carrying packages, designing posters, and "adopting" several French orphans.

Josephine County children divided the work according to grades. High school boys made bedside tables while the girls made bags, layettes, and similar items. The grade school students made wash cloths, tray cloths, and napkins. Children also competed for prizes to collect the most magazines and first class paper. The Red Cross then sold the items to fund programs.

(Oregon State Defense Council Records, State Historian's Correspondence, Box 1, Folder 16, 37, 38, 45)