Travel Less to Win the War

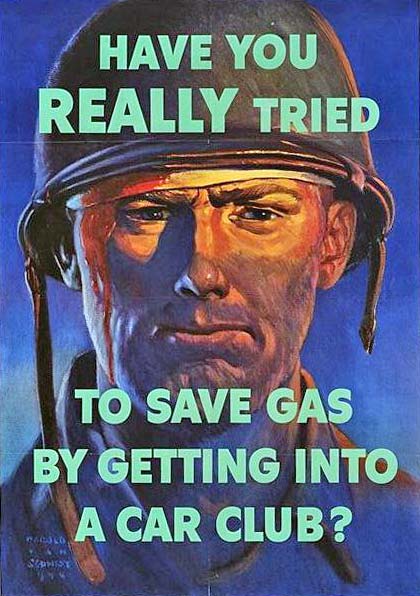

Car clubs, or ride sharing, helped the troops at the same time it helped drivers get the most of rationed resources, such as gas and tires. Save Gas poster courtesy Northwestern University Library

Car clubs, or ride sharing, helped the troops at the same time it helped drivers get the most of rationed resources, such as gas and tires. Save Gas poster courtesy Northwestern University Library The need for increased war production, with many defense plants working around the clock, led to transportation capacity bottlenecks across the country. Moving staggering amounts of material and workers across town and across the country in a time of shortages required greatly increased efficiency along with the sacrifice of long held habits, especially related to the use of cars. Officials decided to whittle away at the problem from a number of angles. Some solutions included ride sharing, staggered work hours, and pleas to limit far-flung vacations.

Factors Contributing to the Problem

Several factors contributed to limit the potential of several transportation modes, particularly the nearly 30 million passenger cars in the country. Americans fell in love with their cars in the decades before World War II as people embraced the freedom to go anywhere anytime they chose. This growing dependency on the automobile caused many streetcar and trolley lines to fall into disrepair or close as William Crawford, director of the Oregon Economic Council, recounted: "Mass-transportation was then a very sick industry, crying out for business." Many of these lines would require significant effort to rehabilitate.

Footnote

1 Oregon's War Transportation Board noted in 1942 that "mass transportation companies simply do not have sufficient rolling stock to take care of the increased traffic" in part because "there were approximately 5,000 undelivered transit vehicles on order." Production restrictions, while later eased, were the culprit.

Footnote

2

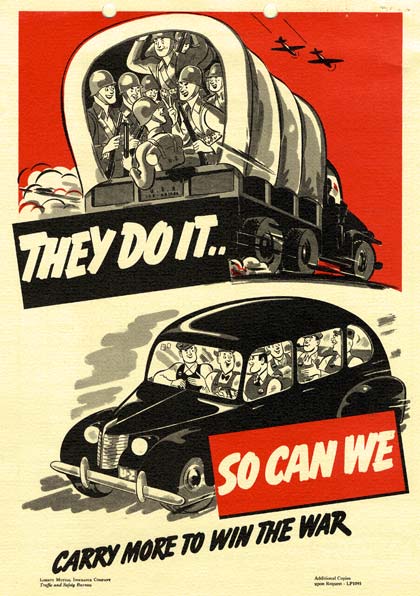

If the troops could ride share, so could home front workers as this graphic shows. (Folder 9, Box 14, Defense Council, OSA)

Enlarge image

If the troops could ride share, so could home front workers as this graphic shows. (Folder 9, Box 14, Defense Council, OSA)

Enlarge image Meanwhile, other shortages and priorities exacerbated to the problem. The extreme shortage of rubber resulting from Japanese control of 90% of the rubber producing areas caused significant fallout throughout the transportation sector. Moreover, employment was increasingly concentrated in defense production areas such as Portland, Seattle and Los Angeles. This overtaxed every part of the physical and social infrastructure including housing and schools. The concentration especially took its toll on existing local roads and mass transportation facilities while creating demand for new roads and transit lines to cope with the traffic jams and crowded buses and trains.

Footnote

3 At the same time, shortages of labor, truck parts, lumber, asphalt and other vital resources even made it difficult to maintain existing roads and bridges, let alone contemplate large scale expansions.

Footnote

4

The government's war production solutions to shortages of materials such as steel and rubber caused new practical and social problems for the average citizen. New car production was severely curtailed and purchases were off limits to the public for the duration of the war. Soon both automobile tires and gas were rationed in an effort to make the rubber supply last as long as possible. Along with problems finding tires and gas, those cars on the road faced increasing difficulty finding replacement parts. As a consequence, officials promoted the wisdom and patriotism of ride sharing, staggered work shifts, and other measures designed to wring efficiencies from the transportation system. On top of it all, new calls came for an end to any unnecessary travel such as vacations far from home, a blow to an overworked public with plenty of war economy money in its pocket.

Ride Sharing

Since experts estimated that "about 85% of us normally get where we are going by automobile," it was only logical that car sharing would be a key element in the effort to get the most out of the transportation system. The federal Office of Defense Transportation spearheaded efforts to get more Americans car pooling. The office noted that the average number of passengers per vehicle stood at less than two in 1942, which meant that "where one automobile and its tires could serve 5 persons, it is actually serving less than 40% of its capacity." Officials reminded citizens that "failure to participate in group-riding plans is to waste rubber, and wasting rubber in the light of today's conditions is nothing short of disloyalty to the war effort."

Footnote

5

Image source: "Car Sharing Club Exchange and Self-Dispatching System" Publication, U.S. Office of Civilian Defense, 1942. Oversize Records, Defense Council Records, OSA

Image source: "Car Sharing Club Exchange and Self-Dispatching System" Publication, U.S. Office of Civilian Defense, 1942. Oversize Records, Defense Council Records, OSA In addition to the patriotic aspect of ride sharing, officials wanted to convey other benefits. Catchy slogans such as "Carry More to Win the War," "Share and Spare Your Car," and American Legion's nationwide "4 in 1" campaign would only go so far. And, as the Oregon Economic Council director noted: "Rationing will automatically bring many riders into groups, but this business must be better organized." Potential riders needed to be convinced that participation would not be too inconvenient. Here, the easiest sell was to workers in big industries or office settings. State employees, many of whom worked around the State Capitol in Salem, quickly organized their own ride share committee. Industrial plant groups formed to save money, tires and time by helping to reduce some of the choking traffic jams, especially around huge defense plants such at the Kaiser shipyards. But according to officials other types of drivers were more problematic: "Women and drivers going on errands are sharing their cars the least; they are likely to be driving all alone. Businessmen and white-collar workers are not doing nearly as well as the factory workers."

Footnote

6

Traffic jams, such as this one at the exit to the Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation shipyards, prompted officials to stagger shift times to even traffic flow. (Biennial Report, Highway Dept. Records, OSA)

Traffic jams, such as this one at the exit to the Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation shipyards, prompted officials to stagger shift times to even traffic flow. (Biennial Report, Highway Dept. Records, OSA)

Several methods of organization arose, many focused on subgroups such as store and office workers, mothers taking children to school, and suburban commuters. One method sponsored by the U.S. Office of Civilian Defense was called the "Car Sharing Club Exchange and Self-Dispatching System." Anyone wanting to participate would fill in a card at an exchange office that included particulars such as address, commute hours, and phone number along with whether he was seeking a ride or passengers. A member of the transportation committee operating the exchange would place the card in the appropriate zone that represented the area in which the person lived. Riders were free to look through the cards to find rides or passengers that best suited their needs. All ride sharing arrangements and possible fees were made between the individuals, not the exchange. Of course, officials encouraged participants to be deliberate about spelling out the responsibilities of each member of the car pool. Issues such as lateness, bad manners, or personal hygiene deficiencies could lead to friction, or worse, since "failure on the part of anyone to assume his responsibility will introduce complications that may doom the plan to failure."

Footnote

7 Staggered Hours

Officials also looked to alleviate transportation bottlenecks by promoting staggered shift starts and stops. But the process could become complicated quickly and planners were warned that "ill-advised staggering of hours may create more severe peaks than now exist." Planners were advised to complete detailed surveys of the shift starting and stopping times of major industries, schools, and businesses and then create graphs that showed the peak hours of travel. Officials used a simplified example to illustrate the next step:

Assume two plants about a mile apart, each discharging 1,000 persons, one plant stopping at 4:30 and the other at 4:45. While this appears to represent a balanced load, it actually does not. Suppose the travel time from the first plant to the critical point [area of congestion] is 20 minute. The passengers will arrive there approximately at 4:50 p.m. Assume the travel time from the other plant, located closer to the critical point is only five minutes. They would then reach the same point at the same time, producing a very undesirable overloading. By advancing the hours of work in the first plant so that employees stop at either 4:00 p.m. or 4:15 p.m., this peak can be eliminated. A later closing at the second plant would have the same effect.

Footnote

8

Officials wanted to know if this man was planning to travel for necessary business or to work on his golf game. They set guidelines for travel to help people decide. (Folder 5, Box 15, Defense Council, OSA)

Officials wanted to know if this man was planning to travel for necessary business or to work on his golf game. They set guidelines for travel to help people decide. (Folder 5, Box 15, Defense Council, OSA)

Because local stores didn't have fashions to suit her style, this well dressed shopper claimed she needed to travel to distant cities. (Folder 5, Box 15, Defense Council, OSA)

Because local stores didn't have fashions to suit her style, this well dressed shopper claimed she needed to travel to distant cities. (Folder 5, Box 15, Defense Council, OSA) Of course, the planning process could be more complicated in real world settings. Planners had to take into account how one shift change would affect not just one other plant, but potentially many plants, schools, businesses, mass transit systems and roads. And each of these entities in turn could affect the others. Some plants, especially related to defense industries, needed to change schedules quickly to fit the ever-changing production demands of the war effort, adding a further layer of complexity. Officials chose to portray the system as more of a "living" organism and acknowledged that "imperfections in the plan may develop which will require review and adjustment." They recommended that planners secure approval of any plan from representatives of industry, labor, schools, transportation companies, and other stakeholders before setting it in motion. And, experts underscored that a potential loss of production, not to mention the frustration of thousands of commuters, could result from a poorly planned effort: "Extreme caution is necessary and expert guidance should be sought before any attempt is made to shift hours."

Footnote

9 "What is Necessary Travel?"

Shortages of labor and equipment brought stern lectures about the nature of necessary travel. By late in the war, more than 300,000 railroad workers and an undetermined number of bus line workers had entered the armed forces. There were also shortages of railroad cars as Office of Defense Transportation officials explained: "In peacetime, Christmas travel usually fills all of our 7,000 sleeping cars and most of our day coaches as well. But today, half of our sleeping cars and over 15 percent of our day coaches are needed to carry troops on duty." If people hoping to see relatives or just get away from the grind of work traveled as much as they wanted, the system would overload and cause military disruptions. This would inevitably trigger rigidly imposed travel priorities that nobody wanted so officials appealed to "everyone's conscience" in guiding travel decisions.

Footnote

10 They described three types of travel:

NECESSARY

Travel that will help win victory at the front and keep us efficient at home. Necessary travel includes: military travel, including furloughs, official and company business, urgent family business, family emergencies, and trips to doctors, dentists, hospitals.

PERMISSIBLETravel that may sometimes be necessary to keep the life of the country going efficiently. Permissible travel includes: visits to service men, necessary shopping trips, and vacation travel from home to the place where one spends his holiday, and home again.

NONESSENTIALTravel that cannot in any way help us to win the war. Nonessential travel includes: social visits, trips to sports events, theaters, fairs; unnecessary shopping trips; tours, including vacation excursions; and trips to conventions, trade shows.

Footnote

11

To make room for the armed forces and those traveling on war business, officials called on pent up travelers to "stay at home in crowds."

Some organizations, such as the American Bankers Association, gave up their large annual conventions and instead published a "convention in print" containing speeches and resolutions that would have been heard if the meeting had been held. Officials also implored citizens to do more with the resources in their own community instead of demanding outside speakers or entertainment, saying that "local speakers have a lot to say and rapidly develop the skill to interest and please an audience." People were told to use their imaginations and self-reliance since parks and resorts were often too far away and "many sources of education and amusement are drying up." Instead, why not do something in "that big shaded vacant lot up the block...?" Or, turn the attic into a game room, or fix up that "outdoor play equipment lying neglected in somebody's yard."

Footnote

12 The Vacation at Home Program

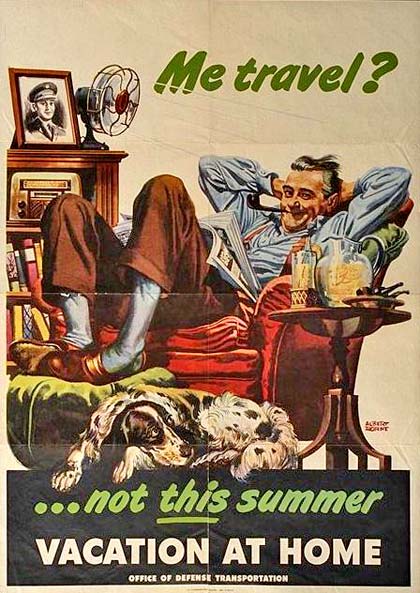

This man made vacationing at home look downright relaxing. Vacation at Home poster courtesy Northwestern University Library

This man made vacationing at home look downright relaxing. Vacation at Home poster courtesy Northwestern University Library Travel crunches became especially bad late in the war as hundreds of thousands of troops redeployed to the West after the defeat of Germany, gearing up for the assault on Japanese forces in the Pacific. Oregon was just one state swamped by the "transport of more troops than the West has ever seen." Moreover, War Department officials anticipated the discharge within a year of 1,300,000 men "who deserve prompt transportation home." Other large movements included "battle-weary men returning from the Pacific areas for recuperation leaves" and thousands of American prisoners from Japanese-held areas. The Army Surgeon-General also reported that 30,000 casualties were reaching the mainland every month, adding to the urgency of the problem.

Footnote

13

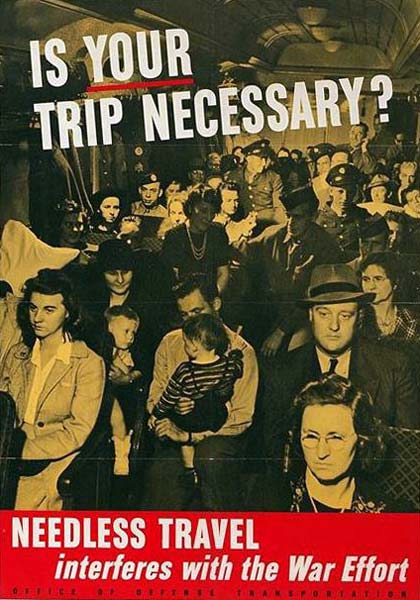

Train travel was often crowded and hectic. Needless Travel poster courtesy Northwestern University Library

Train travel was often crowded and hectic. Needless Travel poster courtesy Northwestern University Library In response to the added strain on the transportation system, and because they were "compelled to re-emphasize facts about wartime travel," Office of Defense Transportation officials highlighted the "Vacation at Home" promotional campaign in 1945. They urged communities to form Vacation at Home committees consisting of representatives from entities such as municipal government, churches, labor unions, radio stations, theaters and restaurants. Authorities envisioned local activities that would be limited only by the imagination of the community. But, just in case, they offered suggestions. For example, radio stations could conduct "Our Town at Home" broadcasts from backyards and porches that highlighted "interesting 'stay-at-home' families in the community." Movie theaters could offer "special 'Vacation-at-Home Nights,' with amateur stage acts. Labor unions could sponsor functions including picnics, rollerskating parties, United Nations dances, and folk-song parties. Cities could stage parades, sandlot baseball leagues, and pet and hobby shows. They could also promote the further deferment of vacations with promotions "along the lines of 'Stay at Home this Summer - Buy Extra Bonds with the Money You Save and Plan a Real Vacation After the War.'"

Footnote

14

The conditions were often likened to cattle cars as many times people were thankful even for standing room.

While government efforts convinced a large number of Americans to vacation at or near their homes, travel skyrocketed nonetheless. In 1944 railroads logged three times the number of passenger miles as in 1941 while intercity buses saw their mileage double over the same period. Along with the two million military passengers on duty or furlough each month, vacationers crowded into the train cars. Conditions were likened to cattle cars as many times people were thankful even for standing room. A black market flourished in Pullman car reservations. Scalpers capitalized by selling tickets at $10 to $50 markups while travel agencies tacked on $20 "service charges" to reservations. In concurrence with government campaigns, one railroad ran advertisements telling potential travelers: "You'll be more comfortable at home."

Footnote

15