"Do They Want This System...to Become a Useless Farce"

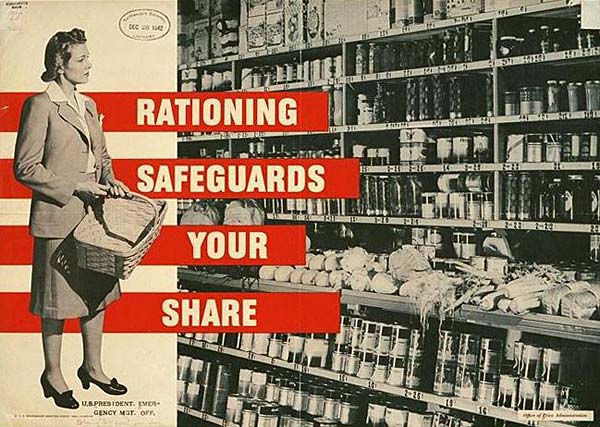

Posters say rationing is the fairest way to deal with shortages. Rationing safeguards image courtesy Northwestern University Library

Posters say rationing is the fairest way to deal with shortages. Rationing safeguards image courtesy Northwestern University Library

As if overseeing price controls weren't enough of a job, the federal Office of Price Administration (OPA) also presided over the bigger job of rationing. The OPA set up complicated rules for rationing everything from beef to bubble gum and from sugar to shoes. In the process, the office became everyone's favorite wartime scapegoat while black markets flourished. Despite

the complexity and grumbling, most Americans grudgingly admitted rationing was a necessary part of the war effort.

A Matter of Fairness

While price controls aimed to keep inflation in check, rationing was designed to distribute scarce goods fairly. OPA official E.W. Eggen put the issue in practical terms while he was a guest on a 1943 KGW radio show in Portland: "Suppose the demand for coffee exceeded the supply (which it does) and there were no rationing. What would happen then is that the woman who got [to] the grocery store first would get coffee and the woman who arrived late would get none. That means that the woman working in a defense plant, with not much time for shopping around, would be coffeeless so that the woman who has little else to do but shop would have more. It means that the woman who has no children to tie her home would have plenty of time to stand in line and get coffee, whereas the mother of a family would not. The same principle would apply to towels, sheets, shoes, dresses, any other type of commodity in which shortages might develop."

Footnote 1

Mrs. E.W. St. Pierre of the State Defense Council, put it another way: "Rationing is essentially democratic,...[it] protects the 'little man' who is unable to pay exorbitant prices for articles of which limited quantities exist."

Footnote 2

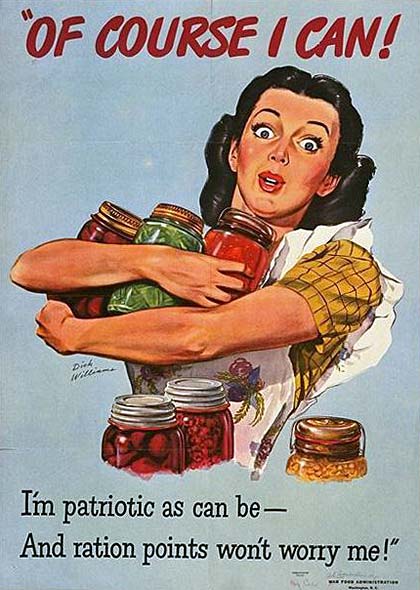

Patriotism was a selling point for rationing. Image no. ww1645-73 courtesy Northwestern University

Patriotism was a selling point for rationing. Image no. ww1645-73 courtesy Northwestern University

Even though thousands of items became scarce

during the war, only those most critical to the war effort were rationed. Key goods such

as sugar, tires, gasoline, meat, coffee, butter, canned goods

and shoes came under rationing regulations. Some important items escaped rationing, including fresh fruit and vegetables. And, much to the relief of millions, whiskey and cigarettes went unscathed by regulations, although shortages appeared from time to time.

A Complicated System Develops

The mechanics of rationing programs changed over time but remained replete with red tape, including coupons, certificates, stamps, stickers

and a changing point system. Sugar, the first item rationed nationwide in May 1942, started the process, followed by coffee. Oregonians lined up at local grade schools staffed by

teachers and volunteers who took depositions on how much sugar each family already had at home and then issued ration books containing coupons good for a year's supply. Over time the number of rationed items grew as did the red tape. Eventually three billion ration stamps a month, each less than an inch square in size, would be passed from the cluttered handbag of the consumer to the retailer, who passed them on to the wholesaler, who sent them to the manufacturer, who had to account for them to the federal government.

Footnote 3

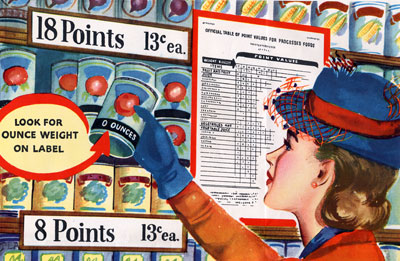

Posters gave shoppers advice on how to use their ration books. (Box 5 of 28, Education Dept. Records, OSA)

Posters gave shoppers advice on how to use their ration books. (Box 5 of 28, Education Dept. Records, OSA)

Soon other items were rationed

including processed goods such as canned, jarred, dried, frozen

and bottled products, followed by meat, fish

and dairy items. Two ration books were distributed to "every eligible man, woman, child, and baby in the United States." One contained blue coupons for processed goods while the other contained red coupons for meat, fish

and dairy products. Each person started with 48 blue points and 64 red points each month. Thus, the shopper for a family of four had a total of 192 points for processed food and 256 points for meats, fish

and dairy products. Each month brought new ration stamps as the old ones expired. Each stamp had a number on it designating the points it was worth and

a letter showing which "rationing period" the stamp could be used. Each rationed product had a point value that was independent of the price.

The point value could fluctuate depending on scarcity and grocers were required to keep current "official point lists" posted. Thus, a scarce can of beans might have a point value of 14 while a more plentiful can of corn might have a value of 8. At the checkout counter, the shopper was to remove the proper amount of stamps in the presence of the clerk. Point management was critical to effective shopping since the number of points available was limited by the rationing period. Moreover, grocers could not make change so shoppers were advised to "use high-point stamps first, if you can."

Footnote 4

By 1944 constantly evolving regulations resulted in a "simplified" plan that, among other things, introduced one point tokens to be given as change.

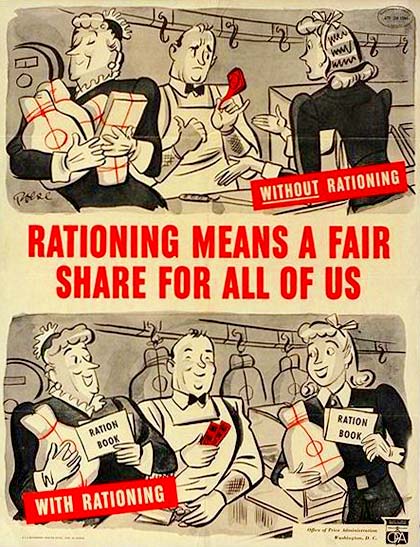

In an ideal world, everybody smiled thanks to rationing. Cartoon image courtesy Northwestern University Library

In an ideal world, everybody smiled thanks to rationing. Cartoon image courtesy Northwestern University Library

The elaborate system of gasoline rationing caused more headaches.

Each driver was assigned a windshield sticker with a letter of priority ranging from A to E. Cars used only for pleasure driving wore an A sticker worth one stamp redeemable for

3-5 gallons a week, depending on the region and the period. Commuters were assigned B stickers worth a varying amount of gas depending on their distance from work. E sticker holders received as many gallons as needed but this designation was reserved for policemen, clergymen, and similar professions. Farmers were granted as much gas as needed but faced a daunting amount of paperwork to claim it.

Footnote 5

Additional systems developed for other rationed products such as car tires and tubes.

"They Can Cheat..."

"They can cheat — it is always possible to cheat on any set of rules. But do Americans want to? Do they want this system designed to be fair to all, to become a useless farce?"

As with price control issues, the mostly volunteer bureaucracy of local war price rationing boards had their hands full looking after the OPA program that had endless opportunities to cheat. OPA officials acknowledged

they were at the mercy of the good will of the consumer: "Our rationing system can be made to work with simplicity and fairness if all Americans everywhere will cooperate and use their ration stamps properly. They can cheat — it is always possible to cheat on any set of rules. But do Americans want to? Do they want this system designed to be fair to all, to become a useless farce?"

Footnote 6

Officials published a list of violations related to how ration books were used,

all while trying to combat a pervasive rationalization that

said "I know I shouldn't do this, but I guess just this once won't ruin the country...." The list of transgressions included trying to make purchases with loose stamps. These could have been lost or stolen and OPA regulations said the retailer was forbidden to accept them. Lending a ration book to a friend was also a violation. The reasoning was that some people who ate frequently at restaurants and didn't need all of their stamps often gave them to friends who would then "be getting double their fair share. This kind of neighborliness must be foregone for the duration." The solution? The frequent diners were expected to destroy any extra ration stamps instead--an unlikely option.

Footnote 7

A Flourishing Black Market

Black market grocers illegally offered "under the counter" rationed items to shoppers. (Box 5 of 28, Education Dept. Records, OSA)

Black market grocers illegally offered "under the counter" rationed items to shoppers. (Box 5 of 28, Education Dept. Records, OSA)

In reality, large and small violations of rationing and price control regulations combined to form a flourishing black market. Typically, this consisted of consumers paying prices above the established limits or buying goods without the required coupons. Many customers, flush with money from high paying defense jobs, were willing to violate the law to buy a

really good cut of meat for a special occasion or a rare pair of shoes that would go perfectly with a new dress. Retailers found a number of ways to work the system and customers were warned not to buy rationed items without coupons: "In order to replenish his stock from legitimate sources, your dealer must have your stamps to turn in. Otherwise, you know he is purchasing from a Black Market." In a variation on the theme, some retailers asked customers to give them their unused ration stamps, thereby allowing the retailer to purchase merchandise that could be sold during the next ration period without the need to demand stamps. Once again, consumers were asked to destroy any unused stamps rather than give them to a grocer.

Footnote 8

One study estimated that warnings about black market activities

were issued to 20%

of American businesses, while nearly 7% were charged with illegal activities. Still, few were prosecuted or convicted and those who were usually received small fines--hardly a deterrent.

Footnote 9

While some social stigma existed, the rationing program was so unpopular and the black

market

so widespread that many people would "look the other way" as they had with alcohol use during Prohibition.

Caption: "Six million fighters are in training right now in the U.S. Each one gets at least 7 pounds of meat a week." (Box 5 of 28, Education Dept. Records, OSA)

Caption: "Six million fighters are in training right now in the U.S. Each one gets at least 7 pounds of meat a week." (Box 5 of 28, Education Dept. Records, OSA)

Hoarding became a mainstay of the black market. Many tried to "beat the game" by hoarding goods about to be rationed while using the ironic justification of "I'm just stocking up before the hoarders get there."

Footnote 10

Portland office OPA official E.W. Eggen tried valiantly, if naively, to make hoarding look like a losing proposition, citing three reasons it wouldn't work: "First, it's unpatriotic, and public opinion would make the would-be hoarders very unhappy. Second, you will have to report your present goods on hand when you get your ration cards. Third, you can't possibly anticipate in advance exactly where shortages will develop. Just as a case in point, the greatest single run on a single item handled by department stores was the rush for all-wool men's clothing last spring. Yet, today [a year later] it is still plentiful."

Footnote 11

Organized Criminals Get Into the Action

Predictably, criminals soon produced counterfeit rationing coupons, which they then sold to gas stations and drivers.

More serious violations

occurred, many at the hands of organized crime. Gas rationing, particularly disliked, fell victim to many schemes. The government claimed that "the gasoline black market involves, in many cases, experienced criminal rings, and is even drawing teen-age youngsters into its operations in dangerous numbers." Predictably, criminals produced counterfeit rationing coupons, which they sold to gas stations and drivers. The OPA estimated fake coupons accounted for 5% of

gasoline sales in the country. Criminals also stole vast amounts of coupons. The Washington D.C. office of the OPA lost real coupons worth 20 million gallons of gas to theft while thieves in Cleveland stole coupons for five million gallons. Meanwhile, other crime resulted in connection with meat rationing. The so called "red market" involved selling low-grade meat for higher-grade prices or selling meat that contained more fat or bone than allowed by federal regulations.

Footnote 12

In Sympathy With Hitler or Hirohito?

Even if much of the population "looked the other way" or chalked it up to being a petty sin, others saw the potentially corrosive effect that could result from a prevalence of low-level crime such as rationing violations. Mrs. E.W. St. Pierre of the State Defense Council used her typical hyperbole in lamenting the situation as she saw it in an August 1942 bulletin:

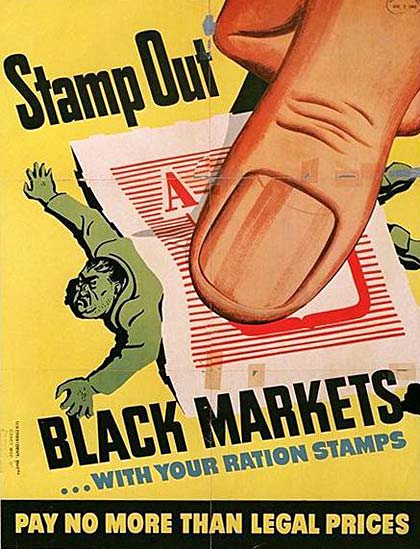

Posters tried

to enlist citizens in the fight against the black market. Stamp out black markets image courtesy Northwestern University Library

Posters tried

to enlist citizens in the fight against the black market. Stamp out black markets image courtesy Northwestern University Library

The American public is being rationed on sugar and rubber today, and tomorrow many more things may be added to this list. ...From this situation has arisen a genie which may undermine our whole war effort, unless an understanding American people lend a hand. It is obvious that there are not sufficient law enforcement officers in the land to detect all evasions of these regulations. A 'black market' has sprung up, bootlegging these materials to persons willing to pay the price. Buyer and seller are equally guilty; they are both disloyal, dishonest, and traitorous to their country. Great hidden stocks of materials, undeclared by their owners when the Government made its check of essential materials, are now finding their way into these markets.

Only a person secretly in sympathy with Hitler or Hirohito would knowingly buy from such a source, for dealers in such hidden supplies are part of a great fifth column movement of the Axis powers. Every loyal American must be aware of this situation. Report at once any suspected infringement of these regulations. 'I know where you can get a tire' ... ---well, find out where and report it at once to your nearest Office of Price Administration or War Production Board. The American people must keep eyes and ears open to defeat this attempt to undermine the war effort of our country.

Footnote 13

Related Documents

"Facts You Should Know"

"Facts You Should Know" Statement No. 3, Office of Price Administration, Nov. 1943. Folder 8, Box 35, Defense Council Records, OSA.

Notes