"Reading is Even More Popular Than Poker..."

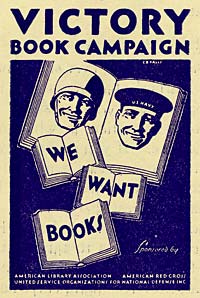

The Victory Book Campaign aimed to raise the morale of servicemen and others in

the war effort. (Folder 42, Box 29, State Library Records, OSA)

The Victory Book Campaign aimed to raise the morale of servicemen and others in

the war effort. (Folder 42, Box 29, State Library Records, OSA)

Servicemen pursued

various types of recreation

during the war, but no form was more highly recommended than reading. The activity would not only expand the mind, distracted the reader from the ugliness of war during lulls on the battlefield, from the otherwise drab military camp surroundings, or from many of the tempting, but forbidden, forms of recreation often available in nearby communities. And the Victory Book Campaign to supply the millions of servicemen with wholesome and educational reading material would be yet another way

Americans could contribute to the war effort.

The Need to Read

Officials knew from the experience of

World War I that providing plenty of books for servicemen during war

could boost morale and the need showed itself soon after

the United States began mobilizing large numbers

of troops in 1940. The Oregon State Library

excerpted a "letter received from a lad in an Oregon Camp" dated

Dec.

10, 1941 in which the serviceman wanted to "find out the possibilities of getting some kind of a start for a library here at camp. As you know the fellows are very much in need of any positive outlet for pent-up emotions & energies." One camp librarian went so far as to say that "reading is even more popular than poker, no matter what the people at home think." In fact, Private Charles Woodbury, who was stationed at Camp Adair near Corvallis but worked as a reference librarian in civilian life, noted on the regular "Ask Your State Library" radio program that reading was second only to watching movies as a recreation according to a War Department survey.

Footnote 1

Victory Books found their way to all

corners of the earth, giving servicemen a satisfying diversion. (Folder 42, Box 29, State Library Records, OSA)

Victory Books found their way to all

corners of the earth, giving servicemen a satisfying diversion. (Folder 42, Box 29, State Library Records, OSA)

It wasn't only stateside servicemen who sought out reading material. The soldiers, sailors, and marines fighting overseas often saw long periods of boredom punctuated by the horror of battle. Many wanted something to fill the down time and take their minds away from the inhumanity of war. One Victory Book campaign brochure showed a soldier reading a book while resting under a palm tree with the caption: "When the fighting slackens and the quiet rest hour comes...then a book is a real companion."

Footnote 2

A National Book Campaign Forms

Efforts to collect books for troops began after the start of the

military draft in late 1940 that lead to millions of men

coalescing in camps around the country.

Many state and local libraries conducted book drives to help

nearby military camps, but it wasn't until the formation of the National

Defense Book Campaign in 1941 that a unified nationwide approach came together. The campaign was sponsored by the American Library Association, Red Cross, and United Service Organizations (USO) and was led by director Althea Warren. She wrote to Oregon State Librarian Eleanor Stephens just days before the attack on Pearl Harbor: "Like most of the librarians in the country during the past year, you have probably felt the pangs from your own conscience or been urged by high-minded library users to start a drive to collect books for the camps." Warren noted that previously Army and Navy libraries had received "appropriations from Congress to buy books and feared these funds might diminish if gifts seemed too plentiful." But the camps had grown so much that the need had become overwhelming, prompting military authorities to give the "go ahead" for a national book drive. Before long, the National Defense Book Campaign operated under the more catchy name of Victory Book Campaign (VBC).

Footnote 3

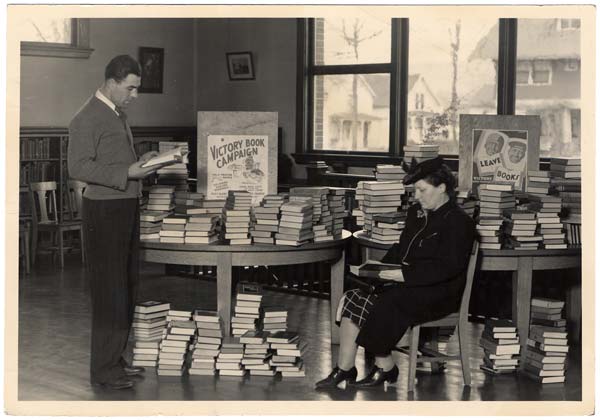

Women sort and package Victory Books at the Oregon State Library for shipment to servicemen. (Enlarge image, Photo no. OSL0023, State Library Records, OSA)

Women sort and package Victory Books at the Oregon State Library for shipment to servicemen. (Enlarge image, Photo no. OSL0023, State Library Records, OSA)

The campaign sought to collect books

suitable for servicemen and to supplement library services already maintained by

the military in libraries at camps, posts, and on ships as well as company "dayrooms" and similar settings. Moreover, books could be packaged and sent in small groups as "Traveling Libraries" to remote military positions. The campaign also would provide reading materials to fill shelves at libraries that the Red Cross and USO maintained for servicemen at clubs and centers in the vicinity of military camps as well as those maintained by the American Merchant Marine Library Association. Any surplus books would be given to libraries near industrial defense plants where population growth had left their resources wanting. Books not suitable for servicemen would be donated to the appropriate body or become part of paper salvage drives.

Footnote 4

Oregon Quickly Organizes its Campaign

Oregon library officials quickly organized to implement the campaign statewide. Eleanor Stephens won a vote to act as director of the Oregon VBC. She assembled a state executive committee consisting of one representative each from the Red Cross and USO as well as a number of prominent librarians from around the state. Local directors and committees formed and armies of volunteers were recruited. An entire distribution system with collection sites, sorting centers, and regional depots needed to be

developed to handle the flow of tens of thousands of books in and out of the

program. Because of the probability of receiving unwanted books, national campaign officials suggested that "trained librarians with the capacity for ruthless discarding should supervise these depots." Books with only "feminine or juvenile appeal" needed to be farmed out to an appropriate distributor. Standardized paperwork, labels, and cards had to be created to deal with tracking and shipping the books. Careful inventories of the number of books collected needed to go onto weekly report cards that could then be used as "ammunition for the campaign committee." Publicity was key so volunteers mounted major efforts to develop special events and drives along with cultivating the local newspapers and radio stations.

Footnote 5

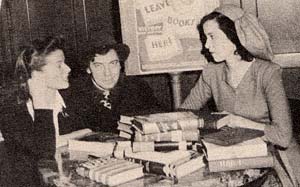

Actress Katharine Hepburn (left) and comic actor Chico Marx (center) were two of many stars of stage, screen and radio who

helped with the national Victory Book Campaign. (Folder 42, Box 29, State Library Records, OSA)

Actress Katharine Hepburn (left) and comic actor Chico Marx (center) were two of many stars of stage, screen and radio who

helped with the national Victory Book Campaign. (Folder 42, Box 29, State Library Records, OSA)

Volunteers and assistance came from wide range of entities in addition to the Red Cross and USO. Among the groups offering help were the American Federation of Teachers, Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, Campfire Girls, Catholic Library Association, League of Women Voters, and the National Education Association. These were joined by countless other groups such as churches, granges, 4-H clubs, labor organizations, fraternal organizations such as the Elks, Masons, and Knights of Columbus, merchant groups, veteran groups such as the American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars, women's clubs, schools, and service clubs such as the Kiwanis, Rotary and Lions. These entities helped by providing volunteer staff for all aspects of the process from planning to publicity to distribution as well as providing financial support, space for collection centers, or even window displays to promote the campaign.

Footnote 6

Major Drives Come Together

While work continued year around, much of the publicity centered on major national drives early in the year. Local volunteers planned promotional efforts to support the campaign. Much of the work went into planning events for the opening and closing days of the drive. For example, the 1943 campaign covered a two month period from January to March. On opening day local workers were encouraged to "dramatize" the festivities by inviting the mayor or other dignitaries to donate the first book during a public ceremony. During the course of the campaign, events such as special luncheons or dinners honoring authors or servicemen could be held. Contests for the best campaign slogans, posters, essays, or collection totals could be held. Libraries could put on exhibits of rare or interesting books that had been donated. Local entertainment venues could be coaxed to accept donated books as the price of admission. Factory personnel offices could collect pledges from employees to donate a certain number of books with "section captains" appointed to make sure the books actually were donated. Offices were encouraged to install a "Five Foot Victory Book Shelf" to be filled weekly and were asked to hold inter-departmental competitions and authorize roving "volunteer book collectors."

Footnote 7

Across Oregon many local volunteers, such as Clatsop County Librarian Glen Burch during the 1942 campaign, worked hard to get the word out:

Volunteers transfer donated books from a van to the Oregon State Library for packaging. (Photographs, State Library Records, OSA)

Enlarge image

Volunteers transfer donated books from a van to the Oregon State Library for packaging. (Photographs, State Library Records, OSA)

Enlarge image

Campaigns relied on large and elaborate networks of collection centers serviced by bookmobiles and other vehicles. Public libraries provided the most obvious collection centers but there were others. School, college, and special libraries participated as did a wide array of locations that drew both foot and car traffic. Suggestions included beauty parlors, drug stores, factories, hotels, theaters, grocery stores, office buildings, oil stations, post offices, railroad and bus stations, and schools. Committees enlisted manufacturers and schools with shops to volunteer to build containers to collect books. Local "motor corps" were formed to clean collection sites on a regular basis and move books to the local collection center, usually the public library. Boy scouts, girls scouts, members of the Junior Red Cross, and similar groups made house-to-house collections as well.

Footnote 9

Not Just Any Book Requested for Donation

The campaign didn't want just any book. State director Eleanor Stephens asked every Oregonian to give at least one good book, but she admonished the reader not to go "to the attic for these books. Our boy's don't want musty cast-off volumes. Give the books that you yourself like - give books that are worthwhile, books that are desirable." While most donations were valuable, many were not. Ruth Stratton, who succeeded Eleanor Stephens as state director, described finding "such things as the Ruth Fielding series, old college catalogs, Women's club directories, books on obstetrical nursing [surely not a favorite with the troops], as well as many books in bad physical condition." Private Charles Woodbury echoed the need to be selective as he decried fiction from 1912 that servicemen saw as old fashioned. When asked on a radio program if he would want to receive such a book, Woodbury replied: "Definitely no, a thousand times no, in fact!" Even though some of these books had been best sellers in their day, he claimed that "the plot and the stilted conversation are as out-dated as the illustrations." The radio host agreed:

Victory Book Campaign graphic. (Folder 42, Box 29, State Library Records, OSA)

Victory Book Campaign graphic. (Folder 42, Box 29, State Library Records, OSA)

In addition to describing

books they did not want, campaign officials spared no effort talking about those they hoped to collect. Among the most sought after according to Army and Navy surveys were current best sellers such as those featured as Book of the Month, Literary Guild and other book club selections. They also wanted popular fiction and non-fiction books dating back to about 1930. Adventure, western, detective

and mystery fiction proved popular. Servicemen studying for promotion or those looking forward to new careers at the end of the war wanted access to technical books, but only if they were less than 7

years old since information

became dated. Popular topics included architecture, aeronautics, chemistry, mechanical drawing, mathematics, military science, navigation, radio

and physics. As a counterpoint to the dry technical books, servicemen

also asked for joke books and

books with

humorous stories, anecdotes, cartoons

and games. Pocket books were popular since they were portable and could be taken into the field.

Footnote 11

Readers browse books

donated to the Victory Book Campaign at the Oregon City Library. Some of the more interesting and unusual books were

placed in an exhibit to generate more interest in the campaign. (Enlarge image, Photo no. OSL0022, State Library Records, OSA)

Readers browse books

donated to the Victory Book Campaign at the Oregon City Library. Some of the more interesting and unusual books were

placed in an exhibit to generate more interest in the campaign. (Enlarge image, Photo no. OSL0022, State Library Records, OSA)

Anecdotal reports of preferences supported the rankings made by larger surveys. According to one report, two categories of adventure/westerns and detective/mystery fiction were most in demand. Some military post librarians commented that "the horse as a means of escape ranks ahead of murder and that Zane Grey is the American Army's No. 1 author." One librarian, Louis Nourse, noted that "one book that seldom stays long on the shelves is Steinbeck's 'The Moon is Down.'" He went on to remark that books about Germans, Japanese, Chinese and Russians were popular. The librarian claimed there was little interest in novels about World War I. Instead, the servicemen had "a great curiosity about the Napoleonic campaigns and the length of tomes like Tolstoy's 'War and Peace' does not daunt them." Nourse claimed foreign language books were in demand while "interest in biography has slacked off in favor of books on current history." He noted interest in classics such as Shakespeare was high as was the demand for poetry since servicemen were searching for "an understanding of the universe" that poetry, philosophy, and religion could provide. Not just any poetry would do, however, since according to Nourse "they don't much care for poetry by little-known authors or material of the erudite university-thesis type."

Footnote 12

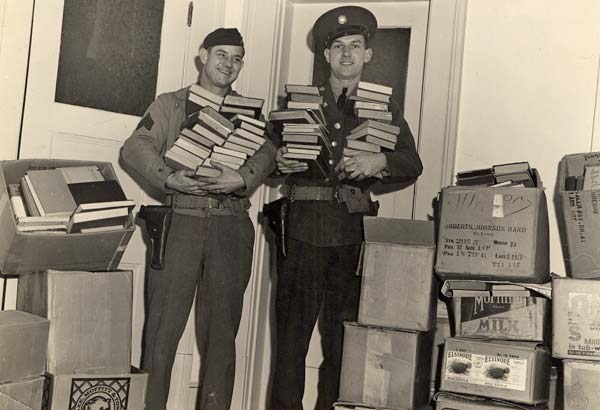

Officials Praise the Campaign

Soldiers participate in the Oregon Victory Book Campaign. (Enlarge image, Photo no. OSL0021, State Library Records, OSA)

Soldiers participate in the Oregon Victory Book Campaign. (Enlarge image, Photo no. OSL0021, State Library Records, OSA)

Oregon's Victory Books program proved a success over its approximately two-year run during which just under 127,000 books passed through the doors. Most libraries in the state collected books that were sent to the Oregon State Library for distribution. Military forces stationed in Oregon had first crack at getting the books, with the remainder shipped to other locations. Most books collected in Multnomah County were distributed to the merchant marines. By June 1943 about 44,000 "carefully selected books" found their way to "all Army Camps, Posts and Stations in Oregon. This includes many general collections for Army hospital libraries, many Traveling Libraries for isolated detatchments [sic], books for Negro troops, for day rooms, and many requests for specific books by individual soldiers."

Footnote 13 About 4,000 books from Oregon were sent to people of Japanese descent held at internment camps located in Idaho, California

and Arizona.

Footnote 14

By 1944 the national campaign

ended after having met the bulk of the need for

books for servicemen. Looking back on the effort, the USO office in New York tallied

impressive totals. Over the two-year life of the Victory Book Campaign, Americans donated nearly 18.5 million books. Of that number, about 10.2 million books, or 60%, were found to be "suitable in context and condition for distribution." Overall, the Army received most of the donated books, totaling over 5.8 million volumes of which nearly 4.5 million were for use in the United States. The Navy got 1.7 million volumes while the merchant marine received over 650,000 books. USO, Red Cross, and related libraries accepted about 1.5 million volumes and about 45,000 books were set aside for "war prisoners." Officials expressed pride in the lean operation, saying that "the low cost of 2.07 cents per book for collecting, cleaning, repairing, and distributing this vital reading material to our fighting forces is final indication of the campaign's success."

Footnote 15

Related Documents

"Ask Your State Librarian"

"Ask Your State Librarian" Radio Program Transcript, Oregon State Library, Oct. 28, 1942. Folder 49, Box 29, Oregon State Library Records, OSA.

Notes