Fighting the Dreaded Postwar Unemployment Threat

A serviceman and his bride cut their wedding cake. Postwar planners counted on women to leave

factory jobs and return to domestic life. (Folder 19, Box 37, Defense Council Records, OSA)

A serviceman and his bride cut their wedding cake. Postwar planners counted on women to leave

factory jobs and return to domestic life. (Folder 19, Box 37, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Even as Oregon and the nation were ramping up

industrial production to fight the Axis in the early days of World War II,

planners were at work envisioning a postwar future.

Officials sought to avoid the dangerously ragged postwar period that

followed World War I during which unemployment spiked and the hopes of many veterans were dashed, leading to social upheaval. As World War II raged on, the private sector, often through industry and trade associations, looked into their crystal balls for clues to postwar development opportunities. And the public sector explored ways to bridge the transition period between a nation fully mobilized for war and one reconverted to a thriving peacetime economy.

A New State Commission Begins Planning

Early in the war, numerous state agencies planned individually for the

postwar period. Hoping for a more coordinated approach, incoming Governor Earl Snell asked the Legislature in 1943 to create a body that would explore state needs and opportunities at a more systematic and comprehensive level. The Legislature responded by forming the Postwar Readjustment and Development Commission, giving it a broad mandate to plan not only for the immediate reconversion period after the war, but also to study and make recommendations for the longterm development of Oregon. The 15-member commission (also known as a committee) included what was billed as a "cross section of the state" consisting of members from "capital and labor, scientists and businessmen" in addition to the heads of several state agencies and the chairmen of the Legislature's House and Senate ways and means committees. The day-to-day activities of the commission were carried out by John W. Kelly, who served as executive director. Kelly, a former newspaper political writer, kept a steady stream of analysis, reports, and recommendations flowing during the next five years.

Footnote 1

Finding jobs for the returning veterans was "the Number One job" for Oregon's Postwar Readjustment and Development Commission. (Folder 34, Box 20, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Finding jobs for the returning veterans was "the Number One job" for Oregon's Postwar Readjustment and Development Commission. (Folder 34, Box 20, Defense Council Records, OSA)

The Legislature called on the commission to consider a number of subjects. Its most immediate mandate was to "explore ways and means of avoiding or minimizing the social and economic disruption and unsettled condition" that could come with the end of the war. The commission was required to plan a program to "absorb and assimilate into civilian business, pursuits and employment the demobilized men and women of the armed forces and men and women released from war industries." The Legislature also wanted a strategy for keeping existing industries and businesses operating and for attracting new ones. Moreover, the commission was to conduct surveys and develop plans for "a long range program of public works and improvements."

Footnote 2

Identifying the Employment Problem

During the war, authorities urged women, such as "Jenny on the Job" above, to work in factories and shipyards. The message was very different after the war when women were asked not to compete with veterans for jobs. (Image no. ww1647-17 courtesy Northwestern University)

During the war, authorities urged women, such as "Jenny on the Job" above, to work in factories and shipyards. The message was very different after the war when women were asked not to compete with veterans for jobs. (Image no. ww1647-17 courtesy Northwestern University)

The commission first focused its attention on the transition to

peacetime. According to John Kelly, "the Number One problem of the committee

of 15 is to see that the boys who return are provided with suitable jobs."

But in the summer of 1943 Kelly could only use an "estimate of 150,000 Oregon boys as a guess" since "the actual number is a military

secret." He also made other estimates since it was important to have some

idea of the number of individuals who would need to assimilate back into the Oregon society and economy. Based on the overall military service numbers, Kelly guessed that "there will be 15,000 casualties among the Oregon boys, for this is a war of blood and tears." He anticipated that about 10,000 to 15,000 would return to their interrupted college educations. Noting that a great many of the returning veterans would possess few applicable peacetime skills or experience since they entered the armed forces right out of high school, Kelly cautioned against easy solutions: "It is foolish to think that a returned veteran can be picked up and placed on a farm, dairy ranch or irrigated land if the veteran has no knowledge of farming. This would leave him stranded. Farming is a technical business and must be learned the hard way."

Footnote 3

Kelly also made guesses about the number of workers affected by the transition

from war industries to the peacetime economy, although he was once again

aiming at a moving target. For example, while citing assurances from the

Federal Maritime Commission that Portland's shipyard industry would continue

in some form after the war, he still expressed deep concerns that

"the shipyards will fold up long before the war is over and Oregon will find upon its hands the army of workers who will expect to be taken care of." He

foresaw a future in which there would be "no need of a day shift, a swing shift, and a graveyard shift. One shift will be ample...with 8000 or less workers. The rest of the workers in the industry, possibly 110,000, will have to live upon their unemployment compensation benefits." Kelly also speculated about the tens of thousands of

workers who came to Oregon seeking jobs during the war, including the "hill billies from the south imported and trained to work on dairy farms." He went on to loosely categorize others as he anticipated the future:

This 6-story high alumina plant in Salem was built in 1945 to process ore for aluminum. Planners saw private industry projects as vital to staving off

postwar depression. (Image no. 42, courtesy Salem Public Library, Ben Maxwell Collection)

This 6-story high alumina plant in Salem was built in 1945 to process ore for aluminum. Planners saw private industry projects as vital to staving off

postwar depression. (Image no. 42, courtesy Salem Public Library, Ben Maxwell Collection)

Yet, others probably would leave the workforce without causing major disruptions according to Kelly. He claimed

most women workers "will return to their domestic duties instead of seeking new jobs in the industrial world. They answered the urgent call of their country until the end of the war and having served well are content to once more become

housekeepers. Their appearance in the industrial world was an adventure and they have no desire to follow it as a career." Likewise,

Kelly saw about 10,000 Oregon workers who were 65-years-old or

older leaving the workforce after the war: "These will have their social security numbers [retirement pension benefits] and will not compete for jobs with younger men." Moreover, he counted an "army of

youngsters" consisting of about 7,000 mostly soon to be

unemployed high school age workers who simply would "resume their education in high schools or college." Finally, Kelly anticipated that thousands of people who flocked to Portland from other parts of Oregon for war industry jobs would return to their shops and farms that they were compelled by the economy to "abandon temporarily."

Footnote 5

Employment Strategies

Despite the view that many former war workers would naturally

be absorbed back into the state's farms, shops, schools, and domestic life,

there was a potential for dangerously high unemployment and social disruption. Thus, in addition to providing unemployment insurance benefits to out of work

Oregonians in the wake of the war, the commission

developed a strategy to employ thousands in public works projects.

But officials stressed that the health of the private sector was of the utmost

importance: "Employment must be stabilized by free enterprise; public works are intended to supplement private industry and serve as a stop-gap." So,

beginning in 1943, the commission began "building a stockpile of worthwhile projects of public works which can be activated quickly to provide employment as necessity demands." The projects involved all levels of government from massive federal dam projects to additional classrooms in small schoolhouses.

Footnote 6

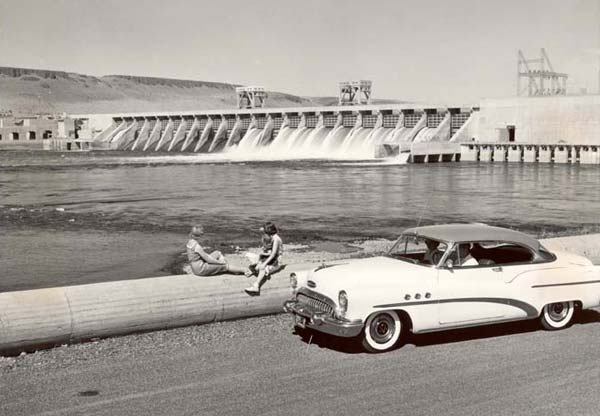

Construction on McNary Dam on the Columbia River in eastern Oregon

was started in 1947, one of many massive federal projects that

kept the Oregon economy humming in the postwar period. The dam was authorized

by Congress in 1945 and completed in 1954. (Photo no. 5832, Highway Dept. Records, OSA)Enlarge image

Construction on McNary Dam on the Columbia River in eastern Oregon

was started in 1947, one of many massive federal projects that

kept the Oregon economy humming in the postwar period. The dam was authorized

by Congress in 1945 and completed in 1954. (Photo no. 5832, Highway Dept. Records, OSA)Enlarge image

Over time, cities, counties, school districts,

and other governmental entities submitted proposals. One of the first problems

was to educate local government officials about the potential problem as Kelly

noted in a radio address to the Oregon Federation of Women's Clubs in 1943:

"In a period when everyone was advertising for help and offering high wages it was difficult to convince the administrative bodies of counties and municipalities that there may be dark days ahead and that inevitably war work would cease and a period of widespread unemployment likely would ensue." At the time, only 17 of 36 counties had submitted their proposals while only 29 of 192 cities had responded. Still, Kelly was encouraged by statements that "with or without federal assistance the counties intend to fly with their own wings and retain control of the projects and not permit dictation from some bureau in Washington D.C."

Footnote 7

Public Works Proposals

There was no shortage of projects to implement even if funding and supply problems delayed work. The biggest spender was the federal government with huge amounts

earmarked for dams such as those in the highly promoted Willamette Valley Project and projects on the Columbia and Snake Rivers. These works promised

thousands of construction jobs as well as benefits in

flood

control, navigation, irrigation

and hydro-electric power. Other anticipated federal projects added tens of millions of dollars to potential payrolls. Reforestation of timber lands that were badly overcut during the war would "require the greatest tree planting program ever undertaken in this State." Grazing restoration in central and eastern Oregon was estimated

to employ 10,000 men. Reclamation work promised not only the initial jobs but also large areas newly suited for farmland on the Deschutes Reclamation Project in central Oregon, the Long Tom Project in Lane County, and others. Calls were also heard to

expand veterans' hospitals as waves of injured and disabled veterans flowed back to the home front.

Footnote 8

A car speeds down a new highway near Mt. Hood circa 1950.

The Oregon State Highway Commission poured millions of dollars of federal and state money into Oregon roads

after the war. (Photo no. 4369, Highway Dept. Records, OSA)

Enlarge image

A car speeds down a new highway near Mt. Hood circa 1950.

The Oregon State Highway Commission poured millions of dollars of federal and state money into Oregon roads

after the war. (Photo no. 4369, Highway Dept. Records, OSA)

Enlarge image

State plans were made for a number of projects around Oregon. Officials proposed improvements, repairs, and expansions of institutional buildings such as the state hospital and state penitentiary. The Oregon State System of Higher Education responded to the request for projects by submitting an ambitious ten-year

building program that would cost 12 million dollars. The plans called for new

buildings, classrooms, dormitories, laboratories and other improvements on

college campuses around the state. The Oregon State Highway Commission proposed

spending 60 million dollars over a three-year period. By late 1943, the highway

commission had toured the state conferring with counties on project priorities and

highway department engineers already had completed surveys and blueprints. Officials said they could start highway projects within a couple of weeks. Of course, John Kelly didn't want any illusions about the nature of much of this work: "This is not a fancy program, but one of physical labor. It will require a strong back. Experience in driving trucks, bulldozers and pick and shovel work." Kelly estimated that highway projects could directly employ 5,000 workers for three years, although he acknowledged that "not all the veterans, however, can do this pick and shovel labor and not all will wish to, but it will be a job until something better shows up."

Footnote 9

Public works proposals flowed into the postwar commission from counties,

cities, school districts and local governments. Kelly

stressed to local governments that the commission was not a "dictatorial

agency" and that it had neither "the authority nor desire to impose its

will upon anyone" in relation to local projects. He noted "no

one knows better than the residents of a municipality or county what its needs are." Still, it became clear that many

smaller governments lacked the expertise

or competent engineers to perform practical planning. The

lack of technical

consultants made it difficult to determine if a project was feasible, to

estimate costs

and prepare blueprints. In spite of the hurdles, surveys and correspondence with local governments revealed plenty of ideas for growth in

communities that had suffered through the Depression.

Counties often aimed to build or improve county roads or replace aging courthouses.

Cities looked to pave more streets, add sidewalks, install sewers and sewage treatment plants, or renovate city halls. Meanwhile, school districts sought to repair or

add to school houses. In fact,

many districts planned on a bigger scale, such as in Bandon, Eugene and elsewhere, where officials wanted to build entirely new high schools and school facilities like playgrounds and gymnasiums.

Footnote 10

Seeing Results

Many Oregon counties replaced their courthouses

during the late 1940s and 1950s. The Curry County Courthouse (above) in Gold Beach was completed in 1958. (Image no. 20130910-D8C_4186, Oregon Scenic Photos, OSA)

Enlarge image

Many Oregon counties replaced their courthouses

during the late 1940s and 1950s. The Curry County Courthouse (above) in Gold Beach was completed in 1958. (Image no. 20130910-D8C_4186, Oregon Scenic Photos, OSA)

Enlarge image

Many of John Kelly's assumptions and predictions proved correct

in the years after the war. As he relished to point out,

doomsayers were wrong about the certainty of massive unemployment in the

postwar period. Instead, and at least partially because of the actions of the

postwar commission and other government agencies, "the unemployment load was not unduly burdensome." As Kelly predicted, about 40% of workers from other states returned home, although they did receive millions of dollars in unemployment benefit checks from Oregon. Meanwhile, "housewives withdrew from the labor pool; elderly workers had their social security; [and] young people resumed their schooling." The state's unemployment fund saw heavy drains for a few months but then recovered as

job openings appeared. The distribution of jobs during this period created some

problems since many unemployed workers refused to leave their Portland area

housing and unemployment benefits, no matter how modest, for jobs in other areas of the state with chronic housing shortages. Housing shortages were made worse by widespread shortages of materials from bathtubs to wiring as American industry struggled to reconvert from producing helmets and hand grenades to refrigerators and radios.

Footnote 11

Chambers of commerce worked with local authorities to promote postwar projects such as new streets and sewers. (Folder 34, Box 20, Defense Council Records, OSA)

Chambers of commerce worked with local authorities to promote postwar projects such as new streets and sewers. (Folder 34, Box 20, Defense Council Records, OSA)

While there were significant postwar problems, measurements of the

growth in Oregon's economy were encouraging. The number of businesses subject

to the payroll tax rose from 9,000 in August 1945 to 16,600 in May 1948. Wages and

salaries as well as income from businesses and property saw healthy gains

from 1945 to 1947. Civilian employment in the state rose by nearly 300,000 workers

from 1940 to 1948 to over 628,000. Meanwhile, unemployment dropped to a modest

22,000 by August 1948 in spite of significant population gains since 1945. In fact, population growth kept the economic ball rolling.

For example, a postwar commission report cited a "notable increase of youngsters...[that] caused the school districts of Oregon to launch frantically, a building program to accommodate these children."

Footnote 12

The rising economic tide came with the help of public spending. A 1946 postwar commission report pegged the estimated cost of government

postwar programs in Oregon at over 800 million dollars, a staggering sum at the time.

While not all projects

made it to completion, a significant number

did, which in turn triggered more hiring by construction contractors and other private sector businesses. At the same time, according to the postwar

commission's

3rd biennial report, "practically every incorprated [sic] town in the state is attempting to provide services to meet [the] demands of the new population. This means additional police and fire protection, paving and sidewalk maintenance, more street lights and teachers." The report noted that even with the agonizingly chronic shortage of new automobiles, there still was one passenger car for every three people, leading to the proclamation that "the horse and buggy days are gone forever and the hitching rack has been replaced by the [parking] meter."

Footnote 13

Related Documents

"Oregon War Dads Speech,"

"Oregon War Dads Speech," by John W. Kelly, Aug.

5, 1943. Governor Snell Folder 2, Box 2, Postwar Readjustment and Development Commission Records, OSA.

"Post War Unemployment,"

"Post War Unemployment," Radio Transcript by John W. Kelly, Sept.

29, 1943. Governor Snell Folder 2, Box 2, Postwar Readjustment and Development Commission Records, OSA.

"...Ten-Year Building Program,"

"...Ten-Year Building Program," Oregon State System of Higher Education, circa June 1944. Higher Education Folder,

Box 1, Postwar Readjustment and Development Commission Records, OSA.

Notes