Delivery trucks such as this 1912 Ford Model T plied the streets of Oregon's cities and towns much less frequently during World War I. Defense council planners wanted businesses to curtail wasteful practices to help the war effort. (Image courtesy wasanonline.com)

Delivery trucks such as this 1912 Ford Model T plied the streets of Oregon's cities and towns much less frequently during World War I. Defense council planners wanted businesses to curtail wasteful practices to help the war effort. (Image courtesy wasanonline.com)

While conservation of food and other war necessities helped, national and state leaders saw the need to institute additional controls on the economy to further the war effort. The State Council of Defense for Oregon responded with both legal requirements and public appeals to make the economy more efficient and focused. Two of its departments illustrate the thrust of the efforts.

Department of Commercial Economy

The defense council sought to improve the efficiency of businesses so more manpower and money could be directed to essential war industries. Yet, it realized strangling the economy could be disastrous. So, the council chose what it considered a middle course.

During the peacetime economy, commercial businesses had developed a liberal system for deliveries and exchanges of goods for consumers. Often, businesses would send deliveries out several times a day on multiple routes. Special deliveries were frequently free. And lenient return and exchange policies meant some consumers would abuse the system by ordering and trying out products or clothing without the intention of purchasing them. While not causing problems before the war, officials saw it as a drain on labor resources that could be better used elsewhere. Thus, the department started a campaign to encourage businesses and consumers to limit their practices. Businesses were asked to adopt the following economies:

- One delivery per day per route

- Elimination of free special delivery

- Limitation of return and exchange privilege to three days from date of purchase.

In a way modern businesses and consumers would find intrusive, the defense council took a serious stance on implementing efficiencies in the economy. It backed its resolve with the following policy on merchandise exchanges.

Yet Oregonians responded and stores reported substantial savings. Large department stores were able to eliminate the need for a credit and exchange desk. And many businesses actually exceeded the defense council's expectations. For example, merchants in Eugene stopped making deliveries entirely. And, merchants in Falls City and Albany planned to follow suit.

The department sought other limits on commercial businesses. Citing a lack of 12,000 skilled and unskilled laborers, they

noted: "We are moved, therefore, to ask in all seriousness for a readjustment in all nonessential industries and vocations as will release...the maximum man-power of our State." The goal was twofold:

- Merchandisers generally should close at 6 p.m.

- Women should be substituted for men in merchandising and "all other callings of service" whenever such a substitution would "not injuriously affect their well being."

Along with regulating portions of the economy, the government appealed to the public to take voluntary steps to make the economy more productive and efficient. (Image courtesy National Archives)

Along with regulating portions of the economy, the government appealed to the public to take voluntary steps to make the economy more productive and efficient. (Image courtesy National Archives)

The second goal echoed the prevailing opinion of society: "Men are needed for productive labor. They must be reserved for such work and not drawn therefrom to do nonessentials." The success of the endeavor, reminded the department, rested "entirely upon the patriotism and cooperation of the citizens of the state to carry out in letter and in spirit the purpose sought."

Building Permit Department

At the request of the federal War Industries Board, the defense council took action in another significant area of the state economy. To save labor, material, and transportation resources for the war effort, the council limited new construction projects in Oregon to those deemed "essential" to the war effort.

- Repairs or extensions of no more than $2,500 to existing buildings if no other government permit were required.

- Repairs or extensions of no more than $1,000 to farm buildings if no other government permit were required.

All other non-governmental construction projects were required to apply to the Building Permit Department for a permit to proceed. Oregonians wishing to build needed to file an application and swear to its accuracy. It then fell to each county chairman of the State Council of Defense for Oregon to decide on individual permits. Among other things, he was to reject the application "if the labor and materials are such as could be utilized in some other way to help toward winning the war, and there is no real necessity for the work going ahead at this time...." Approved applications required the county chairman to write a report giving reasons for the approval. All the paperwork was forwarded to the state defense council and, if approved there, was sent to Washington D.C. where a permit would be issued. Wartime did, indeed, breed bureaucracy in the building industry.

Other Controls

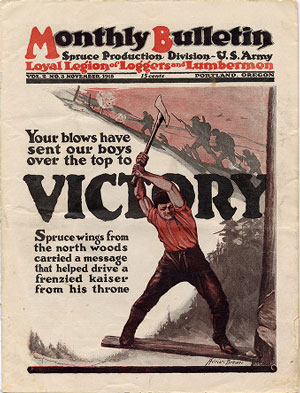

The monthly bulletin of the Spruce Production Division and the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen exhorted the men to work hard to help "drive the frenzied kaiser from his throne."

The monthly bulletin of the Spruce Production Division and the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen exhorted the men to work hard to help "drive the frenzied kaiser from his throne."

Along with the economic controls managed by the defense council, the federal government instituted numerous other actions in the name of war production. Concerned with the growth of labor unions and the Socialist Party, the government took over all spruce production in western Oregon and Washington. The newly formed U.S. Army Spruce Production Division began logging, milling, and shipping spruce, which was seen as essential for manufacturing airplanes for the war effort. Beginning in 1917, the army constructed mills at Coquille and Toledo as well as two mills in Washington. Eventually the division produced a total of 54 million board feet of airplane wing beams in Oregon. By the time the mills later converted to private ownership, the Spruce Division left an extensive railroad network in Lincoln County that fed its modern Toledo sawmill.

Also partially based on the potential for disruptive action by labor unions such as the IWW, the federal government created the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen. Billed as an employer-employee union, it put thousands of men to work. Members were required to pledge to help the nation to produce war materials and, most importantly, to pledge not to strike. Meanwhile, the government set up the Emergency Fleet Corporation to contract with shipyards in Portland, Astoria, Tillamook, and Marshfield to produce both steel and wooden hull ships for the war.

Notes

(Oregon State Defense Council Records, Publications and Ephemera, Box 8, Folder 4, Oregon State Council of Defense News Letter, November 1918; Oregon Blue Book history section)