Many Oregonians serving in World War I were captured and became prisoners of Germany. The following is the story of one prisoner of war (POW).

A 17 Year Old Enlists

Miller's parents allowed him

to

enlist at 17 (OSA)

Miller's parents allowed him

to

enlist at 17 (OSA)

Determined not to miss the fight, young Everett Gerald Miller left his home in Ruch in southern Oregon's Applegate Valley. He traveled south to Kermitt, California and enlisted in the Army as a private in a field artillery battery. The Army stationed Miller at two camps in California before sending him to Texas for a six month stint at sprawling Fort Bliss.

A long, hot, dry summer in Texas seemed interminable to this eager young soldier. His days were spent drilling and waiting to be "sent across." The length of the wait gave Miller plenty of time to feel homesick as the poem to his mother shown in the sidebar reveals. To Miller's chagrin, he took ill and was forced to delay sailing to Europe for a month. But eventually, in May 1918, he left for France.

To the Front

Everett Miller saw duty on the front lines soon after his arrival in Europe. Later, on the night of July 14 while fighting at Chateau Thierry, he helped move the artillery guns of his battery into position to fire on German positions. The large artillery pieces were pulled by sets of horses that had to be moved back to a "horse line" until they were needed to pull the artillery again. Miller went back with the horses but the group was under heavy fire from the Germans. They lost about seven or eight men and about 27 horses as a result of the bombardment. Miller suffered no injuries. The next morning he and the mess sergeant started back to the artillery guns with a tank of water. That was the last time Miller was seen by his battery.

View artillery photographs.

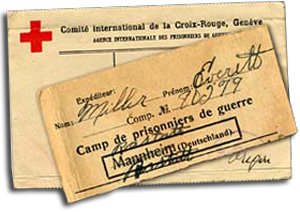

While a prisoner in Germany, Miller sent cards to his family through the Red Cross. (OSA, Oregon Defense Council Records, Personal Military Service Records, World War I, Box 3, Jackson County, School District No. 40)

While a prisoner in Germany, Miller sent cards to his family through the Red Cross. (OSA, Oregon Defense Council Records, Personal Military Service Records, World War I, Box 3, Jackson County, School District No. 40)

Prisoner

Three weeks passed before an artillery friend of his heard news. Apparently, Miller had been gassed, captured by the Germans, and recuperated in a hospital. Later, he was sent to a prisoner of war camp in Langensalza, Germany.

The Red Cross located him, kept his family in Oregon posted, and carried letters and cards as much as possible. One card sent by Miller found him working on a farm, apparently with prisoners of other nationalities. Later, he was moved to another camp at Rastatt that at the time had only American prisoners. This suited Miller well since "we get along fine." Finally, in December, weeks after the signing of the Armistice ending hostilities, a Swiss Red Cross train arrived at Miller's camp. Apparently, he and the other prisoners had no other way to leave Germany.

Other Prisoners

Everett Miller did not reveal the specifics of his imprisonment. However, other soldiers reported that the hardships began immediately after they were captured. Just reaching the destination of the prison camp could be an ordeal. One prisoner, Reginald Morris, remembered the scene:

Once in camp, the experience didn't improve. The men often were separated out for work according to their skills. Still, most worked in back breaking manual labor in mines, farms, machine shops, loading docks, or similar settings. Military discipline among the prisoners sometimes was the first casualty in captivity. In some camps the changes were subtle at first but then escalated into an "every man for himself" mentality. In this scenario some men stole food from others and the weakest died first. Sickness could become a death sentence quickly.

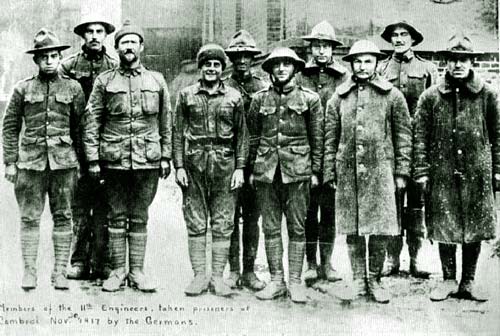

American prisoners of war, 1917. (Legacy Preservation Library, Forward-March, Page 127a) View POW photographs.

American prisoners of war, 1917. (Legacy Preservation Library, Forward-March, Page 127a) View POW photographs.

Housing was often primitive. In one place, Morris had to sleep on a stone floor with only a bit of straw to limit the cold. But, "straw could only be kept by sitting on it; as soon as your back was turned, it was taken by your neighbouring bedmates." Another soldier, Victor Denham, reported equally poor conditions: "The sleeping quarters were of wood and so old that the beams and roofs were alive with wood lice and bugs, which dropped on our faces as we tried to sleep, and gave out a horrible smell when squashed. When we complained, our guards thought it a huge joke." Most of the men moved outside and slept on the ground to escape the lice and bugs.

The prison guards, of course, could make life miserable. Denham, believed the guards who had not been to the front tended to be sadistic, while those who had experienced the horrors of the trenches offered more compassion. For example, when Denham was put in a punishment cell by the guard in charge, one of the guard's subordinates waited awhile and then "came along to release me with a fatherly pat on the head."

Hunger was common in the prison camps. Denham typically received horse bean soup with a few small cubes of meat for lunch and a slice of black bread with the occasional small herring for dinner. Reginald Morris described another sort of problem:

Notes

(Oregon State Defense Council Records, Personal Military Service Records, World War I, Box 3, Jackson County, School District No. 40; firstworldwar.com: Memoirs of Reginald Morris, Victor Denham)