The arms race between Great Britain and Germany in the decades before World War I saw a boom in the construction of state of the art battleships such as this British Dreadnought built in 1906. (Photo #63367, www.history.navy.mil)

The arms race between Great Britain and Germany in the decades before World War I saw a boom in the construction of state of the art battleships such as this British Dreadnought built in 1906. (Photo #63367, www.history.navy.mil)

Building Pressures

A number of circumstances involving European powers in the years leading up to 1914 contributed to the outbreak of World War I:

- Domestic unrest caused some European leaders to look to foreign policy successes for relief.

-

Intense competition led to the spread of imperialism and resulting friction.

- Nationalism and a rising militarism fed an arms race that spiraled upward.

- France continued to resent its humiliating defeat by Germany in 1870.

- Germany feared encirclement by an alliance of enemies.

- Other nations coveted land they may have once held or that had an abundance of resources for growing industries and populations.

A complex system of secret alliances and commitments were ready for a trigger that would set off military mobilization. The trigger came when on June 28, 1914, the heir to the Austrian and Hungarian thrones was assassinated by a Serb. The event quickly escalated into a volley of ultimatums and then a series of military mobilizations by the major European powers. Although other nations eventually joined the war, the major Allied Powers consisted of France, Great Britain, and Russia. The Allies fought the major Central Powers, which were Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Turkey. Each side was euphoric with patriotism, convinced the war would be short and they would be victorious.

Deadly Stalemate

American soldiers leave the trenches to attack

German lines in France. The image is from film shot by a German officer who was later captured. Image colorized. (OSA, Oregon Defense Council Records, Publications and Ephemera, Box 8, Folder 1) View trench photographs.

American soldiers leave the trenches to attack

German lines in France. The image is from film shot by a German officer who was later captured. Image colorized. (OSA, Oregon Defense Council Records, Publications and Ephemera, Box 8, Folder 1) View trench photographs.

Fighting eventually broke out in Mesopotamia (Iraq), the Dardanelles (part of Turkey), northern Italy, and elsewhere. But the largest battles were in France and Russia. German forces had initial success, sweeping into Belgium and northern France to within 30 miles of Paris on the Western front and making sizable gains to the east into Poland.

Soon, particularly on the Western front, both sides settled into a defensive stalemate. A network of trenches ran from the English Channel to the Swiss border. Artillery pieces, some so large they had to be moved on railroads, fired enormous shells into enemy lines. Barbed wire and other entrapments made movement extremely slow and difficult. Machine guns were placed in fortified positions to cut down the enemy as it tried to pick its way through the shell craters and barbed wire. Poison gas drifted in deadly clouds over the lines. The trenches provided some protection from the dangers. But the trenches were also full of mud, disease, decomposing bodies, insects, and rats. Artillery bombardments sometimes continued around the clock for days, contributing to the debilitating "shell shock" suffered by many soldiers.

In the face of the stalemate, both sides largely fought the war according to standard military doctrine- launch an offensive and overrun the enemy. Generals, often feeling pressure to act and without adequate communications or knowledge of battlefield conditions, ordered great offensives that were destroyed by the new technologies of war. Aircraft and tanks, potent offensive weapons in World War II, were still in their infancy and failed to play dominant roles in World War I.

View tank photographs.

Instead, tens and hundreds of thousands of men would climb out of their trenches and go "over the top" into the no man's land between the lines. Most were armed with only rifles, bayonets, and grenades. Many died within a few feet of climbing out of the trench, mowed down by machine gun fire or blown up by exploding shells. Typically, gains were measured in yards before the offensive lost momentum. The costs were staggering as millions of men were lost fighting over the same ground in places such as Verdun, the Marne, the Somme and Ypres. For example, on July 1, 1916, the British attacked the German trenches on the Somme River in France with 750,000 men. The first day of the battle, the British suffered 58,000 casualties. The battle ended when winter came. Britain had 420,000 casualties, Germany had 500,000 casualties, France had 200,000 casualties. The Allies gained 12 kilometers of ground at their point of deepest penetration.

Strained to the Breaking Point

As a generation of young men died on the battle front, societies suffered the strains of total war on the home front. Governments instituted draconian restrictions and requirements to maintain the war effort. Civil and political rights often were curtailed. Women worked long hours in factories and munitions plants.

German submarines crippled the ability of Great Britain to import needed goods from the U.S. and elsewhere before the development of convoys stemmed the losses. Conversely, British naval blockades severely limited the movement of vital materials needed by the Central Powers. Food production declined and shortages of many essentials grew more acute. With brief exceptions, over the years of grinding warfare, morale was sinking in the trenches and on the home front. In 1917, mutinies swept the French army and a complete collapse was narrowly averted.

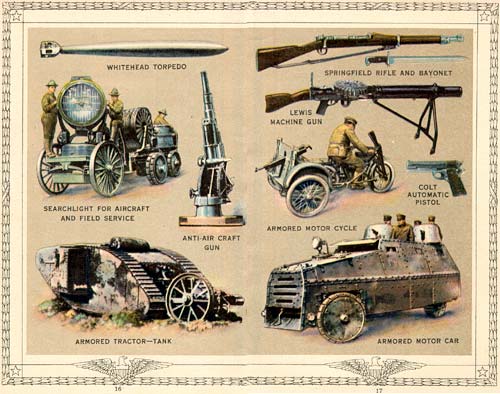

This Prudential Army-Navy Booklet shows some weapons in

America's 1917

arsenal.

(Image, freepages.military.rootsweb.com)

"Oh, the Yanks are Coming..."

This Prudential Army-Navy Booklet shows some weapons in

America's 1917

arsenal.

(Image, freepages.military.rootsweb.com)

"Oh, the Yanks are Coming..."

By 1917 both sides were exhausted. The failure of countless offensives had taken its toll. Finally, in April, after a series of naval and diplomatic provocations, the U.S. declared war on Germany. Still, it took several months for the American soldiers to begin to make a significant difference. Rankling impatient Allied leaders, U.S. General Pershing insisted his troops be adequately trained and that they fight under American command.

Although American entry into the war was a tremendous blow to the Central Powers, events in Russia encouraged Germany and its allies. The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 led to a treaty in early 1918 that ended Russian hostilities and gave up valuable land and resources to Germany. The German army now had one less front to worry about and enjoyed access to large amounts of wheat and oil. Buoyed by this good fortune but worried by the ever increasing American military presence, the Germans gambled everything on a massive offensive on the Western front in March 1918. Improved strategy and tactics yielded their biggest advances in four years of trench warfare.

American soldiers train with machine guns for duty in World War I. (OSA, Oregon State Defense Council Records, World War I Photographs)

American soldiers train with machine guns for duty in World War I. (OSA, Oregon State Defense Council Records, World War I Photographs)

But the Allies, now fortified by growing numbers of Americans, counterattacked and forced a long German retreat. The "Yanks," as the American troops were called, proved instrumental during this period in battling the Germans at Chateau Thierry and driving them out of Belleau Wood. In July 85,000 Americans helped the French mount a successful counteroffensive on the Marne River between Rhiems and Soissons. And, the American First Army under Pershing took over a southern front and routed the Germans by September. Later that month Pershing attacked the German lines between Verdun and Sedan. This Meuse-Argonne engagement, while costly in terms of casualties, proved to be a crucial American victory.

It joined victories by British and French forces to turn the tide on the Western front. Coupled with the effective disintegration of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Central Powers defeats elsewhere, these events signaled the beginning of the end. The German government sued for peace and the Armistice ending hostilities became effective on Nov. 11, 1918.

Oregon's Role in the War

After the war, the state compiled detailed statistics about Oregonians who served in the war. The categories include the following:

|

Army service

|

35,216 |

| Navy |

7,109 |

| Marine Corps |

1,511 |

| Nurse Corps |

243 |

| Yeomanettes |

87 |

| Total in service |

44,166 |

|

|

| Volunteered |

24,386 |

| Drafted |

19,780 |

| Officers |

2,690 |

| Overseas service |

15,605 |

| U.S. service |

28,561 |

| Served in battle |

1,768 |

| Wounded |

1,100 |

| Killed in action |

367 |

| Died of other causes |

663 |

| Total deaths |

1,030 |

|

|

| Discharged as disabled |

1,544 |

| Cited or decorated |

355 |

| Deserted |

191 |

| Dishonorably discharged |

100 |

| Conscientious objectors |

17 |

Complete county level statistics

Complete county level statistics

Notes

(Statistics: Oregon Blue Book, 1931-1932, page 65)