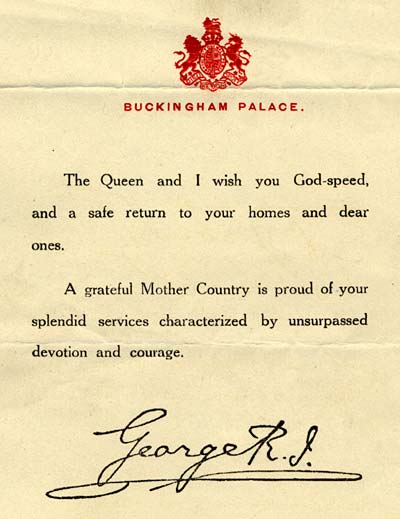

This note of thanks from the British king was given to David Scott before his service in the British Expeditionary Force ended. (OSA, Oregon Defense Council Records, Personal Military Service Records, Box 2, Douglas County, School District No. 39)

This note of thanks from the British king was given to David Scott before his service in the British Expeditionary Force ended. (OSA, Oregon Defense Council Records, Personal Military Service Records, Box 2, Douglas County, School District No. 39)

Voices Less Heard

In addition to the men on active duty in the U.S. armed forces, many others

directly supported the war effort. Among these were perhaps hundreds of Oregon residents who fought with British, Canadian, and other forces during the war. Women also served heroically, often in dangerous conditions. And while hundreds of Oregonians died in World War I, even more were wounded, some disabled for life. Their voices speak to the trials and sacrifices of war endured by those who may not have been as prominent in the headlines of the day.

The voices of minorities are virtually absent from the personal military service histories compiled by the State Council of Defense for Oregon.

This likely is partially due to the relatively small numbers of Native Americans, African Americans, and other minorities who fought in the war from Oregon. But society also tended to overlook the contributions of minorities during the time.

The state historian contacted entities such as the Chemawa Indian School near Salem to request information but had little success.

On Active Service With the Allies

Many Oregon residents, such as those who were citizens of Canada or Great Britain, served in the British Expeditionary Force during World War I. Many answered the call to fight in 1914 and 1915 after the outbreak of war. As with Oregonians serving in the U.S. forces, they risked their lives to serve their countries and protect democracy. However, many of them were exposed to the dangers and sacrifices of war for two or three years longer.

Some veterans saw an advertising opportunity in their return home. The Sutherlin newspaper wrote about David Scott, seated: "David Scott, familiarly known by many of our citizens as 'Scotty' arrived here Monday from Vancouver B.C., having recently been discharged from a Canadian regiment after doing service several months overseas. Mr. Scott has a bullet wound in his left arm as a result of a German machine gun, but he is in shape to do your painting, and guarantee a good job. He is now doing some painting on Ed. R. Paxton's residence." (OSA)

Some veterans saw an advertising opportunity in their return home. The Sutherlin newspaper wrote about David Scott, seated: "David Scott, familiarly known by many of our citizens as 'Scotty' arrived here Monday from Vancouver B.C., having recently been discharged from a Canadian regiment after doing service several months overseas. Mr. Scott has a bullet wound in his left arm as a result of a German machine gun, but he is in shape to do your painting, and guarantee a good job. He is now doing some painting on Ed. R. Paxton's residence." (OSA)

One of them, Charles Franklin Buchanan of Portland, enlisted in the Canadian Army in April 1915 as part of the "Loyal Legion Seaforth Highlanders of Canada." After a promotion to corporal he transferred to the "Duke of Connaught's Own Battalion Canadian Infantry" where he was promoted to sergeant-major. Eager to get to the front, Buchanan resigned his position and enlisted as a private to get into action quicker.

By the beginning of 1916 he got his wish and spent nearly two years at the front. After a fierce 1917 battle in Flanders in which practically his entire company was either killed or wounded, he was once again promoted. By July of 1918 Buchanan earned the commission of lieutenant in the 1st Canadian Reserve. He suffered wounds in September 1918 and again in early October but returned from the hospital to the front quickly both times.

On October 12 he was in the middle of a fight on the Sensee Canal in France. According to Canadian General Philpot, Buchanan "had destroyed a German machine gun nest and had killed several German officers and men single-handed and had dug in on the bank of the canal, awaiting the English artillery, when a sniper killed him."

Described by General Philpot as "a natural leader," Buchanan was posthumously awarded the British Military Cross for his bravery. In his last letter to his parents "he expressed a longing again to visit his parents and other relatives in Oregon. His determination, however, was not to give up the fight until the power of the Hun was broken forever."

Oregon Women Offer Care Here and Abroad

Oregon women served as nurses for the U.S. Army and Navy as well as for supporting organizations such as the Red Cross. Some worked in France and other war torn countries while others served at military camps in the U.S.

Farmer William McKern and his wife, Edna, saw their 20 year old daughter, Enid, off from home near Mt. Vernon in rugged Grant County to start her new life as a nurse. She heard about the government's call for nurses and dreamed about foreign service. On a fall day in 1918, after enlisting with a friend in Canyon City, she began her preparation in the United States Student Nurse Reserve. The reserve assigned her to St. Elizabeth's Hospital in Baker [now Baker City].

Enid McKern wanted to serve as a nurse in France during World War I. She trained at St. Elizabeth's Hospital in Baker. (OSA)

Enid McKern wanted to serve as a nurse in France during World War I. She trained at St. Elizabeth's Hospital in Baker. (OSA)

Once in Baker, Enid began her studies and training. But within a few days, while helping patients, she was stricken with Spanish Influenza. The hospital informed Enid's parents and her mother soon arrived from Mt. Vernon. But Enid developed pneumonia and, after a total of nine days, she died. Her father arrived at the hospital just after she passed away. The family returned her body to Mt. Vernon where she received a military funeral, another victim of the flu epidemic raging throughout the state. She was eulogized as a "big, strong, fine looking girl" who offered her life and died "while serving others that this world might be better."

Many Oregon women, such as Irish born Stasia Walsh of Pendleton, did go on to see extensive service in France. She joined the Army Nurse Corps through the Red Cross in 1918. Already a nurse in civilian life, she quickly became a member of Base Hospital 46 and in March was assigned to service at Camp Lee, Virginia. By the Fourth of July Stasia was shipping out with the hospital for duty in France. She served with Base Hospital 46 and later Base Hospital 81 for the duration of the war, tending to the injured and sick soldiers coming in from the front. Her hospital service in France continued into June of 1919 as the country tried to recover from four years of total war.

Other Oregon women served as doctors in Europe during and after the war. The American Women's Hospitals organization carried out work related to the war and relief efforts. In cooperation with other organizations such as the Red Cross, it operated hospitals and dispensaries in several parts of France. But many of the sick and injured in isolated villages could not travel to the hospitals because of the war-ravaged roads:

The organization carried out similar work after the war in Serbia and the Near East as famine and disease ravaged those areas.

According to the chairman of the national organization, Dr. Esther Lovejoy, "Our Oregon medical women made exceptionally fine records in the American Women's Hospitals overseas service. We have a state of less than a million people and while I cannot say exactly the number, I believe there is only one state with a larger number of medical women in our service than Oregon, according to population." She especially cited two Oregon women, Dr. Mary MacLachlin and Dr. Mary Evans. They served in a hospital in Luzancy, in a devastated part of France, for almost a year. Because of their selfless service, they were decorated by the French government and "made citizens of that municipality [Luzancy]."

The Disabled Return Home

Allen Gribble of Portland was wounded seven times in the war. (OSA)

Allen Gribble of Portland was wounded seven times in the war. (OSA)

The wounded began arriving at the field and base hospitals soon after American soldiers first took to the trenches of France. Many were "fixed up" and returned to the battlefield. Others suffered injuries that would spell the end of their active service. Some were disabled for life.

Most men would live with partial disabilities. Allen T. Gribble of Clackamas worked as a letter carrier before signing up for duty on the Mexican border. He later enlisted in the Marine Corps and, after training, was sent to the front at St. Mihiel in August 1918. Soon in heavy action, Gribble was wounded seven times and lived to tell about it. His wounds included: "Shot through the nose; index finger of left hand shot off; shot through left thigh; shell wound, right knee; shell wound, above right ankle; little finger of the left hand shot off." He finally stopped fighting after the seventh wound when he was shot in the wrist.

The marine was taken to a base hospital where "I can eat three squares a day." Yet, Gribble grew impatient away from the battle: "[I] am anxious to get back at them. If I don't before the war ends I know there are plenty of other Yanks to finish the job." Gribble stayed in France until March 1919. Still, his wounds would leave him partially disabled for the rest of his life.

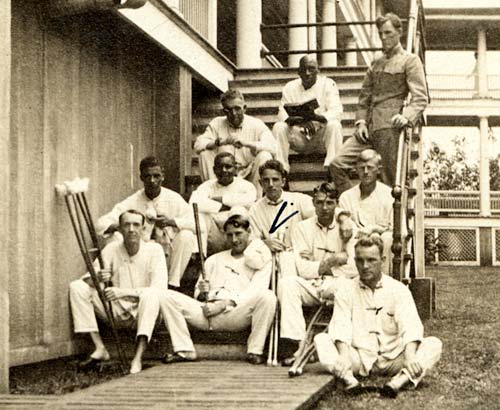

Ralph Boyer, front row center, lost part of a leg in an accident while laying mines. He took advantage of the federal Soldiers' Rehabilitation Act of 1918 to learn new skills after the war in Corvallis. (OSA)

Ralph Boyer, front row center, lost part of a leg in an accident while laying mines. He took advantage of the federal Soldiers' Rehabilitation Act of 1918 to learn new skills after the war in Corvallis. (OSA)

Ralph Boyer went to Corvallis to train for a new life. The 22 year old enlisted to serve in coast artillery for the Army. One day his company was planting mines. A rope slipped and one of Boyer's legs became entangled as he was dragged violently for some distance. His leg broke so badly that it needed to be amputated. According to a major in the coast artillery, "he remained concious [conscious] throughout the ordeal which was three hours. The Dr. who operated spoke highly of his grit...."

Since the accident occurred while Boyer was on duty, he qualified for the help under a new federal disability program. Before World War I, most wounded soldiers died. Eighty percent of those wounded in the Civil War died since an understanding of germs and sterile environments was not well developed. With increased attention to preventing infections, the survival rate improved greatly for American fighters during World War I.

The Soldiers' Rehabilitation Act of 1918 basically responded to the influx of disabled but otherwise healthy veterans returning from the war. Nationwide, approximately 10,000 men were eligible for the program. Many were assigned to business colleges, factories, automobile schools, and other industrial institutions across the country. The act proved so successful that two years later it was extended to civilians with disabilities. It is now seen as a key element in the path toward modern rehabilitation services. Disabled veterans also benefited from the services of the U.S. Veterans Bureau, which ran hospitals for injured and disabled veterans. The bureau consolidated with two other agencies to form the Veterans Administration in 1930.

Disabled soldier Alexander Brander of Scotland carried his war wound shrapnel in a box. (OSA)

Disabled soldier Alexander Brander of Scotland carried his war wound shrapnel in a box. (OSA)

Oregon Agricultural College played host to numerous disabled soldiers and sailors seeking vocational education since the act paid student expenses. Boyer apparently enrolled at OAC. His grade report for the first semester of 1919 shows him earning "B"s in both machine shop and tractor operation.

By May 1919 OAC saw 15 members in the campus group affectionately dubbed the "S. and S. Crip Club," short for the Soldiers' and Sailors' Cripple Club. The men ranged from 20 to 37 year old. One had a broken back, one had lost a leg, and another was blind in one eye. One member, Alexander Brander, a Heppner resident originally from Aberdeenshire, Scotland, carried a box with shrapnel with him as a conversation piece. The shrapnel was removed from his body after he was wounded on the Marne front the year before. The club's purpose at OAC was to direct and improve the "social, mental and moral opportunities" of its members. A faculty member of the OAC Department of Vocational Education served as an active member and advisor to the club.

Notes

(Oregon State Defense Council Records, State Historian's Correspondence, Box 1, Folder 15, 17; Personal Military Service Records, World War I, Scott: Box 2, Douglas County, School District No. 39; Gribble: Box 5, Multnomah County, School District 1; Boyer: Box 1, Benton County, School District 9; Brander: Box 5, Morrow County, School District No. 1)