American soldiers break through barbed wire to attack the enemy in this drawing. Combat engineers, such as Corporal Jones, often had responsibility to cut through barbed wire entanglements as the infantry advanced. (OSA, Historical Annual National Guard State of Oregon, 1939)

American soldiers break through barbed wire to attack the enemy in this drawing. Combat engineers, such as Corporal Jones, often had responsibility to cut through barbed wire entanglements as the infantry advanced. (OSA, Historical Annual National Guard State of Oregon, 1939)

Tough Assignment

After training at Vancouver Barracks in Washington and several months at Camp Greene, North Carolina, Carl W. Jones of Brookings finally made it to Europe in May 1918. As a combat engineer, his job was often one of the most dangerous around. It included clearing the way for infantry to advance. This could mean cutting through masses of barbed wire, installing pontoon bridges, or repairing roads. The engineers were often at the front lines of battle. Clyde Moore, a 23 year old combat engineer from Redmond, quoted one of his lieutenants: "When you look over what an Engineer has to know, you wonder what the H--- anybody else is supposed to know."

Marching alongside infantrymen, Jones carried a haversack that held two days rations, gun, ammunition, gas mask, hatchet, and a pair of quarter-inch bolt cutters (needed to cut the German barbed wire entanglements that were sometimes too strong for regular pliers to cut). A squad of engineers was often attached to each platoon of infantry to cut the ubiquitous barbed wire. Vital to the success of the mission, an engineer had to maintain calm under intense fire and show resourcefulness in the face of incredibly challenging situations.

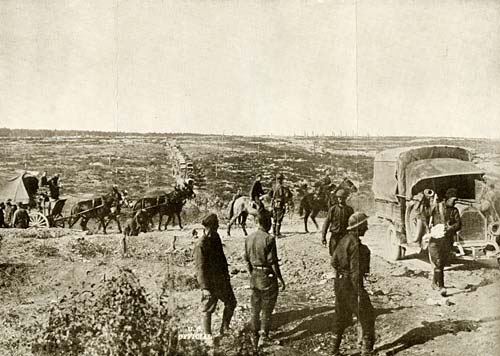

U.S. Army engineers use horses and trucks while building a road in France. Efficient transportation of troops and supplies was vital to the war effort. (OSA, Oregon Defense Council Records, Publications and Ephemera, Box 8, Folder 1) View soldiers on the move photographs.

U.S. Army engineers use horses and trucks while building a road in France. Efficient transportation of troops and supplies was vital to the war effort. (OSA, Oregon Defense Council Records, Publications and Ephemera, Box 8, Folder 1) View soldiers on the move photographs.

"...My Division Went Over the Top"

On July 18 Jones's division advanced in the Chateau Thierry salient of France. As if a portent of the battle to come, the night before the advance "could not have been worse for the wind was awful and the rain terrible and everything as black as charcoal." Earlier he had passed a battlefield where thousands had died the year before and noted:

In order for the division to advance far, it needed to cross the Vesle River. It fell to Jones and his fellow engineers to put a foot bridge across the river. But Jones could see the Germans in the woods on the other side of the river. When the enemy opened fire, his crew would drop as the bullets whizzed by their heads. When a light rocket would flare up, they would drop and lie perfectly still to avoid detection. Eventually, they completed the bridge and the division advanced.

Later, Jones had several more close encounters with German forces as he described in a letter to Curry County:

After the fifth day of the advance, Jones and his outfit were relieved by other soldiers and began to move to the rear. Ironically, after tempting death so many times at the front, he was injured when a gas shell struck just ten feet in front of him. Jones suffered a thigh wound and was slightly gassed but later returned to his company. He attributed the injury to "troopers luck."

Notes

(Oregon State Defense Council Records, Personal Military Service Records, World War I, Box 2, Jones: Curry County, School District No. 11; Moore: Deschutes County School District No. 10)