Sam Hill's vision and Sam Lancaster's engineering are reflected in the Historic Columbia River Highway. The design of loops drew on the lessons learned when Lancaster created the privately-built Maryhill Loops experimental road earlier at Sam Hill's Maryhill community on the Washington side of the river. Shown above are the Rowena Loops. (Oregon State Archives, Scenic Image No. 20160316-9273)

Sam Hill (Oregon State Archives)

Sam Hill (Oregon State Archives)

A Visionary: Sam Hill

As with any large project, many people played key roles in moving the Columbia River Highway from a dream to a reality. Simon Benson, John B. Yeon and Henry L. Bowlby, among others, were indispensable to the effort, but Sam Hill drove the vision.

Hill, a tireless attorney and entrepreneur, promoted the better roads for decades. He was inspired by scenic roads in Europe, such as the Swiss Axenstrasse and the route along the Rhine River with its fairytale castles.

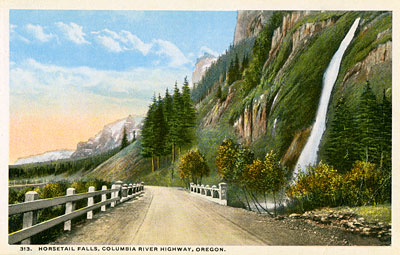

Horsetail Falls drops right next to the original alignment of the Columbia River Highway in this postcard depiction. (Oregon State Archives, Private Donation Postcards)

When the Washington State Legislature balked at funding his plan for a highway along the north bank of the Columbia River, Hill set his sights on Oregon. He invited the Oregon governor and the entire legislature in February 1913 to Maryhill, his community on the north bank of the river near present-day U.S. 97. There he impressed them with his fervor for good roads and with dramatic lantern slides of beautiful European roads. Hill closed the deal with a personal tour of his stunning privately-built good roads example, the Maryhill Loops experimental road.

The politicians responded in part by forming the Oregon State Highway Commission, but it still lacked power and money. Hill recognized that counties would need to pay much of the costs for building the highway. In August 1913, he got the ball rolling by convincing the Multnomah County Commission to fund the start of construction.

Hill also orchestrated the all-important support from Portland’s top civic leaders. He secured the backing of Portland’s two largest newspapers and all of the attention that they could bring to the cause. And, Hill encouraged the private help of citizens such as lumber baron Simon Benson to donate land and money.

Without Sam Hill’s vision and untiring promotion, the Columbia River Highway would not have been possible. The highway as constructed could not have been built earlier and would not have been built later. His timing was perfect.

A Builder: Sam Lancaster

One of Sam Hill’s greatest feats was recognizing the talent of engineer Sam Lancaster. While Hill provided the original vision and the civic promotion for the highway, Lancaster oversaw the marriage of art and science in the design of much of the road.

A postcard shows tourists enjoying the view from the Columbia River Highway in a vintage car. (Oregon State Archives, Private Donation Postcards)

Hill met Lancaster in 1906 and they soon became friends in the cause of good roads. In 1908, Hill invited Lancaster to the First International Road Congress in Paris, where they toured Western European roads with inspiring natural settings and engineering.

Sam Lancaster (Oregon State Archives)

Sam Lancaster (Oregon State Archives)

Three years later, Hill hired Lancaster to engineer the construction of the seven-mile long Maryhill Loops Road, which climbed the steep hills from the Columbia River north toward Goldendale, Washington. Since this was envisioned as an experimental and demonstration road, Lancaster had great latitude in the techniques and material used.

This experience proved invaluable when he was called upon to lead the Columbia River Highway effort in 1913. Lancaster fearlessly mapped the alignment of the road while noting that “there is but one Columbia River Gorge [that] God put into this comparatively short space, [with] so many beautiful waterfalls, canyons, cliffs and mountain domes.” Because of this, he sought to bring the highway close to as many of these features as possible.

Lancaster developed advanced engineering standards to build the highway. For example, he insisted, in all but rare cases, on limiting the grade to no more than five percent and curves to no less than a 200-foot turning radius.

But beyond technical innovations and his knack for solving challenging engineering problems, Lancaster brought a spiritual and romantic appreciation of nature to the work. Humbled by his responsibility, he carefully studied the landscape before aligning the road. All the while he hoped that “we might have sense enough to do the thing in the right way...so as not to mar what God had put there..."