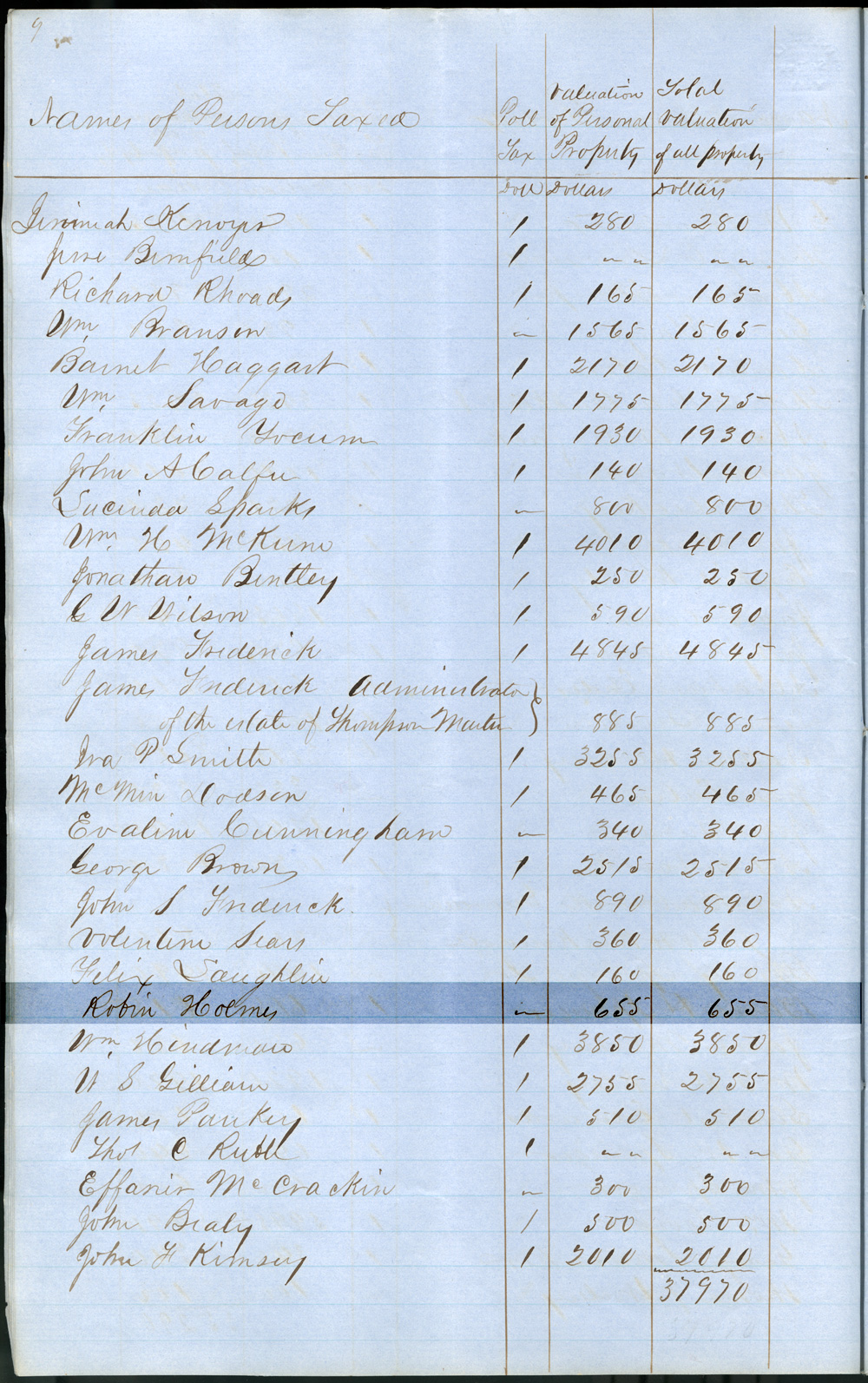

This 1854 Polk County assessment roll shows the value of Robin Holmes personal and total property (highlighted).

Enlarge image

This 1854 Polk County assessment roll shows the value of Robin Holmes personal and total property (highlighted).

Enlarge image Robin and Polly Holmes arrived in Oregon in 1844, as the property of Nathaniel Ford. In their mid-thirties at the time, they brought with them three of their six children. Their other three children were sold off as slaves in Missouri, prior to them leaving.

Before leaving Missouri, Ford promised the Holmes family their freedom upon arrival if they would help him establish a farm in the Oregon Territory. Settling in the Willamette Valley near Rickreall, Ford built a small cabin for the Holmes’ but he denied the family its promised freedom.

By 1850, Robin and Polly had five children and Ford granted them and their infant freedom but kept their other four children as slaves. Harriet, one of the children still held by Ford, died in 1851. Recognizing that Ford would not willingly free the surviving children, Robin began an unprecedented legal battle to get custody of his children.

Robin was up against formidable odds. He had lived his life as a slave, raised in slave culture, bought and sold and was illiterate. He was bringing suit to an influential man with powerful connections, who was also recently elected to the territorial legislature.

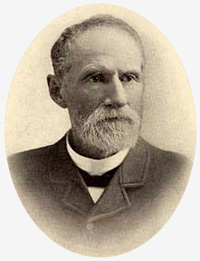

Reuben Boise acted as Holmes' attorney. Boise later served as a delegate to the Oregon Constitutional Convention in 1857.

Reuben Boise acted as Holmes' attorney. Boise later served as a delegate to the Oregon Constitutional Convention in 1857. In 1852, Robin’s attorney, Reuben P. Boise, mounted a credible case against Ford. He filed a writ of habeas corpus in Second District Court in Polk County, seeking the return of the Holmes’ “unlawfully detained” children. The intent of the writ was to require Ford to bring the children to court and explain under what authority he was holding them. If Ford failed to satisfy the court, he would likely be ordered to return the children to Holmes, or so Holmes hoped. According to the initial brief court record, Ford “admits that he detained” the children.

The case worked its way through lower courts and finally reached the bench of Chief Justice George A. Williams of the Oregon Territory Supreme Court fifteen months later. Williams ruled against Ford, declaring that slavery could not exist in Oregon without special legislation to protect it. He then declared the Holmes children free. Following the ruling, and with their rights to their children restored, Robin and Polly Holmes moved to Marion County where they operated a successful plant nursery.