Weaving Together Countless Programs

Many block leaders were conflicted about selling war bonds. They recognized the need but worried about wearing out their welcome in neighborhoods. Cartoon image courtesy Northwestern University Library

Many block leaders were conflicted about selling war bonds. They recognized the need but worried about wearing out their welcome in neighborhoods. Cartoon image courtesy Northwestern University Library

By the fall of 1942, most Oregonians were feeling less concerned about a large-scale Japanese attack on the state. Civilian protection services such as the Aircraft Warning Service and the air raid warning system grew and matured rapidly during the last year and the offensive capability of the Japanese appeared to

diminish. Gradually, more people began to turn their attention away from protecting themselves and to ways they could help the war effort. Much of this was imposed on them through price controls, rationing

and other measures. But there were many voluntary ways to contribute to the cause through war services such as conservation, salvage, buying war bonds, and donating Victory Books. As these programs took on a more prominent role, officials implemented a hierarchical "block plan" to systematically organize and communicate information about the

range of war services. By the middle of 1943, more than 15,000 block leaders and neighborhood leaders were knocking on

front doors around Oregon putting the block plan into effect.

Block Leader Duties

A stylishly dressed block leader heads off to share information with neighbors. (Folder 2, Box 34, Defense Council, OSA)

A stylishly dressed block leader heads off to share information with neighbors. (Folder 2, Box 34, Defense Council, OSA)

Block leaders filled a role

similar to that of the air raid block wardens, only in relation to war services instead of civilian protection. According to the Portland and Multnomah County Civilian Defense Council, block leaders functioned to develop a cooperative unit through "block discussion meetings, rallies, car sharing plans...and any other activity of the

committee's war services." Specifically, they were to explain how households could participate in community programs such as salvage and Victory Gardens; gather survey data needed to develop

war services efforts such as those related to child care and housing; promote participation in war programs such as blood donations and immunizations; and assist the local volunteer office in recruiting volunteers for

defense council programs and

recruiting for paid positions in critical jobs in war industries, professional nursing, and women's branches of the armed services. Block leaders were "supposed to have the confidence and goodwill of the people in your block; you are the morale builder; an information bureau; a solicitor; a salvage worker and many other things rolled into one."

Footnote 1

Organization of the Block Plan System

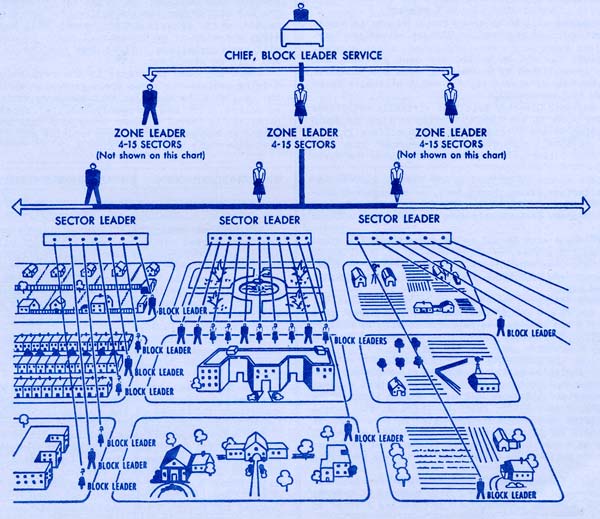

Block leaders served as the "tip of the spear" in a hierarchy designed to transfer information to and from every home. (Folder 25, Box 34, Defense Council, OSA)

Enlarge image

Block leaders served as the "tip of the spear" in a hierarchy designed to transfer information to and from every home. (Folder 25, Box 34, Defense Council, OSA)

Enlarge image

The U.S. Office of Civilian Defense (OCD) organized and promoted the block plan to states in 1942 to be patterned after the

familiar air raid block warden plan. It was

suggested, for the sake of simplicity, the war services plan be

overlaid on the existing geographical boundaries of the air raid plan. The

government asked

cities with a population of 2,500 or more to set up the block plan. The federal Agriculture Extension Service helped develop a similar system

for rural areas that included neighborhood leaders. As part of the plan,

a typical city hierarchy was devised to reach every home. At the top was

the chief of the city's block leader service, followed by zone leaders who

had

jurisdiction over 4 to

15 sector leaders. These volunteers in turn would manage the efforts of a number of block leaders. Each

block leader had responsibility for about 15 families.

Because of varying

housing facilities, a typical neighborhood block with single family detached homes might have one block leader while a more high density block with large apartment buildings might have three block leaders. While the program saw variations to meet local circumstances, officials wanted to avoid overloading block leaders with too many households.

Footnote 2

Portland's block plan grew

directly from the existing air raid warden plan. It started before Pearl Harbor "when those women who are now leaders first volunteered as air raid wardens. On their replacement by men in this job they became assistant wardens, and later were absorbed into the Block Plan, of course, retaining their same geographic jurisdiction. Since this made to order group was at hand to take over the Block Plan it was never necessary to call residents together for an election of leaders, either block, sector or zone."

Footnote 3 Directions for a campaign or drive came

from the defense council to Portland's chief block leader and down the hierarchy to "six district chairmen, then to 55 area chairmen, then to the precinct chairmen, and finally to the block leaders themselves - women who work only in their own neighborhoods, and know the local conditions to be considered [in] any type of appeal or activity."

Footnote 4Training and Advice

Block leader insignia. (Folder 25, Box 34, Defense Council, OSA)

Block leader insignia. (Folder 25, Box 34, Defense Council, OSA)

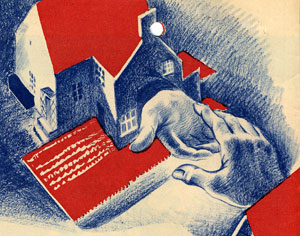

Officials said block leaders

strengthened bonds between neighbors. (Folder 4, Box 34, Defense Council, OSA)

Officials said block leaders

strengthened bonds between neighbors. (Folder 4, Box 34, Defense Council, OSA)

State Defense Council officials stressed the importance of preliminary instruction for block leaders even

though "such training meetings may seem non-essential and time-taking to the busy housewife who is Oregon's typical block leader." If a block

leader wasn't

educated in the basic information about the programs and campaigns, she was at risk of becoming a "mere messenger for the distribution of literature." If she fell to that level, the job might as well go to "some of the willing junior organizations," such as scouting and youth groups that offered messenger services. State officials reminded the block leader she was obliged to provide "the valuable personal message and interpretation of a mature spokesman." In addition to attending lectures or training courses, block leaders were asked to be familiar with the literature they distributed, understand how a particular program contributed to the war effort, and be prepared to answer arguments against programs.

Footnote 5

Block leaders got advice about how to interact with

neighbors as they made

house calls. They were advised to learn the names of everyone in the household and, if possible without "sleuthing," find out about interests and backgrounds. They were to listen attentively to criticism and get answers from their superior if they couldn't respond to questions immediately. Considering so many defense workers worked various shifts, block leaders were to find out the best time to call: "You wouldn't want to ring the doorbell of a graveyard shift worker at ten in the morning. And you couldn't expect a good reception and response more than once if you did." While it was important to be upbeat, officials noted that "your job is not to arouse patriotism, but to show every family you will be contacting how they may

demonstrate their patriotism by cooperating with the campaigns you will be telling them about."

Footnote 6

Officials offered a list of what to do and not do when contacting households, probably much of it based on reports of real experiences by block leaders:

"Don't ask personal questions. Don't gossip; respect confidences. Don't snoop; don't argue or coerce. Don't give orders; ask co-operation. Do be cheerful and resourceful. Don't talk about politics or political leaders. Don't talk about religion, race or color. Don't ask questions you wouldn't want to answer. Do be neighborly and sympathetic. Do be a 'leader.'"

Footnote 7Touchy Subjects

Each block leader was urged to get to know all the families on the block and share information. Many block leaders also solicited during war bond drives. (Folder 25, Box 34, Defense Council, OSA)

Each block leader was urged to get to know all the families on the block and share information. Many block leaders also solicited during war bond drives. (Folder 25, Box 34, Defense Council, OSA)

In addition to educating neighbors, block leaders were asked to gather information for the government. Often that consisted of asking set survey questions but it also involved a more controversial element: "By passing along your neighbors' reactions to your sector leader, who will in turn hand them to your block plan chief, and so on down the line to Washington, the Government may well be kept in closer touch with its people." But officials were quick to downplay any ominous overtones to the request for information about the neighbors: "When we say that you will be bringing back the people's response, it is never meant in a 'Gestapo' or policing sense." Instead of reporting on individuals, block leaders were asked to provide a sampling of the "general feeling" but they would "never be policing or reporting infractions."

Footnote 8

While officials asked block leaders to gather information, they denied looking for data on individuals, wanting instead to learn the "general feeling" of a neighborhood. (Folder 25, Box 34, Defense Council, OSA)

While officials asked block leaders to gather information, they denied looking for data on individuals, wanting instead to learn the "general feeling" of a neighborhood. (Folder 25, Box 34, Defense Council, OSA)

Block leaders expressed reluctance

about direct involvement in

solicitations for money that came with the big war bond drives. Federal officials were torn on the issue. They were hearing that block leaders were resisting calls to sell bonds, wanting instead to continue their education and survey role. To be sure, they were active in recruiting volunteers but that was different from what they saw as more crass solicitations for money. Many feared that soon "the role of the block leader as a friendly neighbor who calls on his fellow neighbors may be jeopardized...." On the other hand, the block leaders were perfectly positioned to pull in huge sums to

fund the war effort and potentially

shorten the war. In typical fashion, the government split the baby. Under a revised policy, it set up conditions under which block leaders could solicit funds. The rules were designed to provide separation of the two roles, even to the extent of calling for a moratorium on all block plan activity while a bond drive was underway. As such, the revised policy stated that "under this plan, the worker is not soliciting as a block leader, but as a volunteer for the particular plan."

Footnote 9

A Myriad of Campaigns

Block leaders across the country encouraged Americans to grow Victory Gardens. These church members responded by breaking ground on their

garden. (Folder 13, Box 36, Defense Council, OSA)

Block leaders across the country encouraged Americans to grow Victory Gardens. These church members responded by breaking ground on their

garden. (Folder 13, Box 36, Defense Council, OSA)

With or without bond drives, block leaders had plenty to keep

busy. In 1943 the OCD released a list of 100 different types of campaigns that had been conducted locally around the country. State officials said

the list "included a variety of projects...for which we in Oregon have felt no need." Still, by the end of 1943 after little more than a year of work, Oregon block leaders had participated in 27 different types of campaigns covering a wide range of war services. They helped with a call for cannery labor; promoted fuel conservation, health education, Victory Books, and Victory Homes; found cots for soldiers to sleep on over weekends; assisted neighbors in interpreting the rationing program; educated people about Victory Gardens; conducted surveys about child care, working women, and nursing; and solicited for war bond drives and war chest drives.

Footnote 10

Portland's extensive block leader service was particularly active. During a six-week period in the spring of 1943, the volunteers participated in a

range of activities. They delivered bulletins, pamphlets

and publications related to price control, fuel conservation, and other topics. They went house to house to give out information on a war bond drive but were reminded that there was "no soliciting or selling in this job, just information." As with any of their efforts, they were not to leave the information in mailboxes or on porches: "It is to be delivered in a personal and friendly call." The first week of May was salvage call week for the Portland block leaders. This meant going door to door asking for discarded silk and nylon stockings. And, in case they collected large amounts, they got a tip to make their job easier: "Knotting the foot of a stocking, turning it inside out and stuffing it with other hose is a handy way to carry them."

Footnote 11

Mrs. Evans Armstrong put in long hours in the Portland block leader program. (Image source: Footnote 14)

Mrs. Evans Armstrong put in long hours in the Portland block leader program. (Image source: Footnote 14)

"When we say that you will be bringing back the people's response, it is never meant in a 'Gestapo' or policing sense." Instead of reporting on individuals, the block leaders were asked to provide a sampling of the "general feeling" but they would "never be policing or reporting infractions."

Many block leaders went the extra mile to make a campaign successful. One Portland block leader told of her

household fat salvage efforts: "All the people in my block are elderly couples. They accumulate such a little bit of fat at a time in these small households that before a regulation pound tin [the smallest amount to be turned in] could be filled some of it might be spoiled. So I've made it my business to collect what they do have regularly and combine these into one larger tin for the whole block's contribution." Another block leader found a household that included a permanent invalid. Upon seeing that the nurse attending the invalid had no opportunity to get out of the house because of her duties, the block leader arranged to come over to relieve the nurse occasionally. Meanwhile,

The Oregonian newspaper saluted Mrs. Evans Armstrong with its "Citation of the Week" for her "energetic, enthusiastic and tireless work" on campaigns. She had just completed a "painstaking house-to-house canvass" for a war bond drive, but she had participated in over 24 campaigns overall since volunteering and totaled nearly 1,300 hours of work in the process.

Footnote 12

Thousands of Oregonians volunteered to be block leaders during the war and in the process helped to pull dozens of programs together in

a more efficient and effective plan. By the middle of 1943, Multnomah County totaled 6,800 block leaders serving 108,000 urban homes. Another 635 neighborhood leaders in the county were in contact with over 6,500 rural homes. Marion County saw nearly balanced efforts by block leaders and neighborhood leaders with just over 1,000 volunteers serving the county's cities and nearly 800 serving in the countryside. Of course, some counties didn't have any cities with populations of 2,500 and relied exclusively on the neighborhood leaders for coverage. For example, Jefferson County in Central Oregon reported no block leaders and only 14 neighborhood leaders. Regardless of numbers, these volunteers contributed in countless ways to help neighborhoods stay focused on the war effort.

Statistical chartFootnote 13

Statistical chartFootnote 13