During the push for national women’s voting rights, Oregon and other suffrage states were featured in marches as examples to be followed. (detail, Library of Congress)

During the push for national women’s voting rights, Oregon and other suffrage states were featured in marches as examples to be followed. (detail, Library of Congress)

Origins of the Woman Suffrage Movement in Oregon

Beginning with the formation of local equal suffrage associations in 1870, the struggle for full voting rights for Oregon women spanned 42 years. The issue of voting rights—also called suffrage or the franchise—for Oregon’s women appeared on the state’s ballot six times: 1884, 1900, 1906, 1908, 1910, and 1912. After 1902, supporters of woman suffrage used the Oregon System with its initiative process to bring their issue directly to the men of the state who would make the decision. Women finally achieved full voting rights in the general election of 1912. With that success, Oregon joined other Western states and territories in extending the vote to its female citizens and providing crucial legitimacy to the woman suffrage movement nationally.

Abigail Scott Duniway. (University of Oregon Library)

Abigail Scott Duniway. (University of Oregon Library) The earliest phase of organization and activity began in 1870 with the formation of local suffrage associations. Abigail Scott Duniway, an early advocate of women’s voting rights, arranged for suffragist Susan B. Anthony to tour the Pacific Northwest in 1871. The success of that tour led to the formation of Oregon Woman Suffrage Association in 1873. Efforts to press the issue of women voting occurred in 1872, when Duniway, Maria Hendee, Mrs. M.A. Lambert, and Mrs. Beatty, an African American woman, attempted to cast ballots in the November presidential election. Their actions were part of a nationwide movement, that included Susan B. Anthony, to extend the franchise to women using the provisions of the 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution. Women’s ballots were not included in the official voting tabulations, and in Anthony’s case caused her to be arrested for voting illegally. Although Oregon women had some limited voting rights in some school elections; their quest remained to have the rights and responsibilities of full citizenship, which included universal suffrage.

During this time period, Duniway established the New Northwest newspaper (1871-1887). Her goal was to promote economic and social rights for women, as well as the right to vote. The paper was filled with news items, poetry, advice, and opinion pieces and served as a conduit between local and national sources. Duniway solidified Oregon’s connection with the national woman suffrage movement by attending national suffrage conventions and arranging tours of the Pacific Northwest for national suffrage leader Susan B. Anthony in 1871, and again in 1896. The tours included lectures by the two women across the state in Salem, Oregon City, The Dalles and Walla Walla, Washington, and later in Eugene and Roseburg. Relations between Western suffragists, including Duniway, and their eastern counterparts, such as Anthony and Anna Howard Shaw, were often strained by different strategic approaches to passing suffrage legislation—Duniway preferring the “still hunt” approach of restrained lobbying while Anthony and Shaw advocated for a much more public style of campaign.

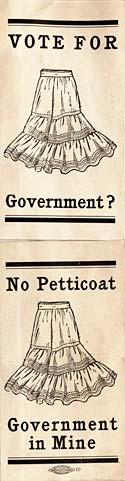

An anti-suffrage advertisement. Many men believed women were not qualified to vote or that they would be tainted by the process. (University of Oregon Library)

An anti-suffrage advertisement. Many men believed women were not qualified to vote or that they would be tainted by the process. (University of Oregon Library) Differences aside, the National American Woman Suffrage Association held a convention in Portland in 1905 in conjunction with the Lewis and Clark Exposition. The energy generated by the presence of nationally prominent suffragists and the local suffrage community during the fair resulted in a more visible and popular Oregon woman suffrage movement. The momentum generated during the summer of 1905 launched a second wave of attempts to extend suffrage to the state’s women.

Carrie Nation personified the national Women's Christian Temperance Union crusade against the evils of alcohol. The call for prohibition complicated woman suffrage efforts in Oregon. (Public Domain Image)

Carrie Nation personified the national Women's Christian Temperance Union crusade against the evils of alcohol. The call for prohibition complicated woman suffrage efforts in Oregon. (Public Domain Image) In 1906, 1908, and 1910 supporters of enfranchising women campaigned to secure that right. Oregon now had the initiative process in place, which allowed supporters to gather signatures to place the suffrage question directly on the ballot. Abigail Scott Duniway and a new generation of younger suffragists, including Dr. Esther Pohl Lovejoy, clashed over campaign tactics. There were differences, too, with the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and its desire to use the vote to prohibit the manufacture and sale of liquor. This fact was not lost on the state’s liquor and business interests, which ran an organized and well-funded resistance to giving women the vote. The three successive suffrage measures lost by increasingly larger margins and gave Oregon the dubious distinction of defeating woman suffrage more times than any other state.

Success at Last

Grass roots organizing by local groups using speeches, meetings, advertising, and the distribution of suffrage literature dominated the state’s early 20th century campaigns for women’s voting rights. After submission by Duniway of another initiative petition to place the woman suffrage question on the ballot for the sixth time, the Oregon Senate Joint Resolution No. 12 and House Concurrent Resolution No. 24 recommended ratification of the equal suffrage amendment to the Oregon constitution in the November general election.

With the 1912 campaign, successful coalition building resulted in alignment with over 75 groups across the state that included men’s equal suffrage leagues, Chinese American and African American women’s equal suffrage leagues, women’s clubs, farm groups, labor unions, and civic organizations. A new generation of Oregon clubwomen united in the final push to gain voting rights for women that included: the Portland Woman’s Club Suffrage Campaign Committee led by Dr. Esther Pohl Lovejoy, Sara Evans, Elizabeth Eggert, and Grace Watt Ross; the Colored Women’s Equal Suffrage Association headed by Hattie Redmond and Katherine Gray; the Chinese American Equal Suffrage League; and the Portland Equal Suffrage League led by president Josephine Hirsch. The campaign stretched around the state and reached a peak over the summer and into the fall with an automobile parade in Klamath Falls, an open air lecture in Drake Park in Bend, a suffrage booth at Prineville’s county fair, and a suffrage luncheon at the Pendleton Hotel.

On November 5, 1912, 52% of the male voters of the state approved extending the franchise to women. With that outcome, the vital right of citizenship was extended to the majority of Oregon women. Many Native women and men were unable to claim U.S. citizenship and the vote until the federal Indian Citizenship Act of 1924. First generation Asian immigrants (male or female) could not become naturalized citizens, and voting rights did not include them at this time.

In honor of her dedication to the cause of woman suffrage, Gov. Oswald West asked Abigail Scott Duniway to author and sign the Oregon Equal Suffrage Proclamation Duniway became the first woman to vote in Oregon when she cast her ballot at the polls in 1914.

The Campaign for National Woman Suffrage

With voting rights secured for Oregon women, many local suffragists continued the struggle for a national amendment. Oregon and the Western states were early leaders in the woman suffrage movement, and their successes were publicized in the push for a national equal suffrage amendment. Oregon’s successful woman suffrage campaign demonstrated the effectiveness of coalition building and proved that women were capable of, and eager to participate in, electoral politics. The U.S. Congress passed the 19th Amendment on June 4, 1919. On January 12, 1920, Representative Sylvia Thompson (D-Hood River) introduced House Resolution 1, and upon its adoption by both houses, Oregon became the 25th state to ratify the 19th Amendment. The 36th state finally ratified the amendment on August 26, 1920, and for the first time since its adoption, the U.S. Constitution included equal voting rights for women.

The following pages illustrate some of the people, organizations, events, and documents that tell the history of the perseverance and determination that finally led to victory and the extension of voting rights to the women of Oregon.

Exhibit Acknowledgements

The

Oregon Blue Book extends special thanks to Janice Dilg and Kimberly Jensen for their help with this exhibit.

Related Documents

Learn More

Visit the Century of Action website to learn more about the centennial of woman suffrage in Oregon:

www.centuryofaction.org