1913—2013: The Centennial of an Important Year for Oregon Beaches

Oregon has a long history of public beaches. But that history has seen challenges that threatened to privatize and fence off the beaches in ways all too familiar to Californians and residents of other coastal states.

Over one hundred years ago Oregon Governor Oswald West engineered the first major protection of public access to the state's beaches, by cleverly convincing the 1913 legislature to declare all Oregon tidelands to be a state highway. That same year saw the birth of Tom McCall, who would later become governor and take up the first significant challenge to the 1913 law.

Traditional Uses of Oregon Beaches

For centuries Native Americans used beaches for transportation, food gathering and other communal activities before the arrival of white settlers in the 1800s. The new inhabitants found that headlands and other geographic obstacles made road building difficult. This naturally attracted wagon traffic to the wide, flat beaches for much of the north-south transportation. The Oregon Legislature recognized this practice in 1899 when it mandated that the shore between low and high tides in Clatsop County would forever be a public highway.

Governor Oswald West helped enact the first major defense of public access to beaches. (Oregon State Archives Photo)

Governor Oswald West helped enact the first major defense of public access to beaches. (Oregon State Archives Photo) Meanwhile, the State Land Board was selling tidelands to private upland owners—totaling about 23 miles by 1901. Seeing the threat to public use if this trend toward private ownership continued, Governor West successfully urged passage of a 1913 bill that declared the entire Oregon shore from low to high tides to be a public highway. West later recalled that his "bright idea" was to remind legislators that "thus we would come into miles and miles of highway without cost to the taxpayer." This creative solution worked for over 50 years, even as the legislature changed the designation from “highway” to “recreation area” in 1947.

A New Public Access Challenge

Beachgoers in many coastal states are unwelcome on stretches of beach.

Beachgoers in many coastal states are unwelcome on stretches of beach. Another threat came in 1966 when Bill Hay, owner of the Surfsand Motel in Cannon Beach, instructed his employees to tell beachgoers who were not staying at the motel to leave a stretch of the dry sand "private beach" in front of the motel. This rectangular area was separated from the rest of the beach by a perimeter of logs placed by motel staff. Inside the perimeter, motel guests were invited to enjoy the provided cabanas and tables free from the trash and other undesirable aspects of the open beach. Others were expected to respect a sign that read: "Surfsand Guests Only."

This drew a public complaint to the Oregon Highway Department, which sent an investigator who confirmed the report. Legal analysis by the state determined that Hay's move had exposed a flaw in the 1913 bill, which technically protected only the wet sands.

The Fight for the Beach Bill

The Highway Department aimed to fix the loophole with House Bill 1601 in the 1967 legislature. Dubbed the “Beach Bill,” it languished and nearly died in committee before the efforts of concerned citizens and State Representative Sidney Bazett revived it and helped it gather momentum. But supporters would face an extended political drama, replete with backroom power plays and staunch opposition by coastal legislators. Many argued that the bill would be an assault on property rights and would be unenforceably vague. Supporters also faced significant resistance from legislative leaders, including powerful House Speaker Monte Montgomery.

Seeking to break the stalemate, an impatient Governor Tom McCall hitched a ride in a helicopter between two beaches with the media watching. McCall, a longtime journalist with a gift for public relations, used the opportunity to make his case directly to the people of Oregon. He purposely planned the trip on a Saturday to assure the largest audience of readers in the Sunday newspapers.

McCall had surveyors pound stakes in the sand to show Oregonians the stark boundary line choices in competing proposals to define public beaches. The media gleefully covered the event and the public quickly and loudly supported McCall’s position. The opposition in the legislature ran for cover and the bill passed easily.

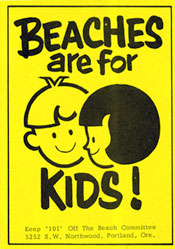

A sticker used by the Beaches Forever campaign to gather enough signatures to put their beach initiative on the ballot in 1968. The resulting Measure 6 fell to a well-financed opposition campaign in the November election. (Western Oregon University Archives, Robert W. Straub Collection)

A sticker used by the Beaches Forever campaign to gather enough signatures to put their beach initiative on the ballot in 1968. The resulting Measure 6 fell to a well-financed opposition campaign in the November election. (Western Oregon University Archives, Robert W. Straub Collection) The final bill as signed into law declared all wet sand lying within 16 vertical feet of the low tide line to be the property of the state. Moreover, it recognized public easements of all beach areas up to the line of vegetation. The law required that property owners seek state permits for building and other uses of the ocean shore and it declared that the public would have free and uninterrupted use of the beaches.

Seeking Further Protections

Still, House Bill 1601 relied on zoning laws to protect the beaches and many people, including State Treasurer Bob Straub, wanted more solid protections. He and a citizens’ group, Beaches Forever, Inc., pushed initiative Measure 6 in 1968 proposing a temporary one-cent-a-gallon gas tax for the state to purchase outright the dry sand beaches.

After leading in the polls, the measure lost to a well-financed, professional anti-gas tax campaign that raised taxpayer doubts about the initiative with a catchy slogan: "Beware the tricks in No. 6."

The Legacy of Public Access

Today, some stretches of beach remain privately owned—vestiges of the State Land Board actions over a century ago. However, state and federal courts upheld Oregon’s right to use zoning laws to regulate development of those lands. In the end, concerted efforts by citizen activists, school children, and political leaders protected public access to some of the most beautiful beaches in the world.

Filmmaker Tom Olsen Jr. noted: "In retrospect we have to be very thankful for Bill Hay—for if he hadn't exposed this loophole—and this issue wasn't addressed until the 1970s or 1980s—there wouldn't have ever been a politically appropriate climate to pass a 'Beach Bill.'"