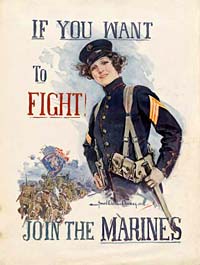

Labor shortages and inflation followed after American men moved from fields and factories into military camps. (Image, Hoover Institution)

Labor shortages and inflation followed after American men moved from fields and factories into military camps. (Image, Hoover Institution)

War and Inflation

The war demanded greatly increased production of a wide range of goods, both agricultural and industrial. But at the same time, it moved significant numbers of workers into the military and away from production. The inevitable results included shortages of both labor and products, leading to significant inflation in the economy.

Agricultural Labor Shortages

Agricultural work, strenuous and low paying, felt the sting of inflation especially acutely. According to one report from Klamath Falls, "Before the war good farm hands could be had from about two to three dollars [per day] and their board. Now one must pay about the same as the factories, mills, etc pay and do not get as good a hands." The going rate rose to about $75 per month plus board.

In many cases, women and girls responded to the agricultural need by taking the place of men in the fields despite the fact that much of the work "was rather heavy for them." Apparently, the labor shortage was exacerbated by "the fact that the men that were to be had would not work and could not always be trusted as the I.W.W.s [labor union operatives blamed by many for subversive activities] and others harmful to the farms and government were allowed to run at large entirely too much."

Shortages in the Factories

Factories and mills in the area held a competitive advantage over farms since the hours were shorter and the work usually was closer to town and its housing, services, and diversions. But factories were not immune from the inflationary pressures. Wages soon increased by 30% to 50% in many cases and "most of the laborers are less skilled than the ones formerly imployed [sic]."

Women stepped in to fill positions in factories and mills too. One student witnessed the profound social change the war economy brought to the local community:

Inflation Hits the Price of Goods

The U.S. Food Administration took steps to conserve food in August 1917 as shortages in Oregon and across the nation worsened. (Image, National Archives)

The U.S. Food Administration took steps to conserve food in August 1917 as shortages in Oregon and across the nation worsened. (Image, National Archives)

Rising labor costs soon led to considerable increases in the price of most goods, including farm crops and animal products.

In Klamath County, beef steers that had sold for about 6¢ per pound on the hoof

before the war rose to about 10¢ per pound, an increase of 67% in a very short time. Pork prices doubled from about 9¢ per pound to 18-20¢. Butter, milk, and

cheese, staples of the diet, rose as well. Before the war a consumer could

purchase a quart of milk a day for a month for about $2.50. That price shot up to

$4 during the war.

The cost of some products rose considerably before the government stepped in

to hold prices down. Herbert Hoover, in charge of the federal Food Administration,

used a variety of means, including price controls, rationing, and the bully pulpit,

in an attempt to slow inflation and reduce demand for products desperately needed to fight the war. In Klamath County, wool had jumped from 35¢ per pound to 60¢

and climbing before the government took action, paying 50¢ per pound. Wheat,

meat, and sugar received a great deal of attention since they were considered

necessary for the war effort. The price of wheat had more than doubled from 1.5¢ to 3.25¢ per bushel locally before government restrictions took hold.

"You Bear It With a Grin"

Despite extensive efforts to lessen the impact of inflationary pressures, the economy was dogged by rising prices throughout the war. But as one Sherman County observer noted: "Wartime works quite a hardship on a person's pocketbook as well as his table, for leaving a restaurant you get a bill for about double what it would have cost you befor [sic] the war, but you bear it with a grin."

Along with rising prices, 14 year old Orvyl T. Howard of Grass Valley saw another inevitable result of war - higher taxes:

Notes

(Oregon State Defense Council Records, State Historian's Correspondence, Box 1, Folder 38)