President Woodrow Wilson tried to keep the U.S. out of the killing fields in Europe. (Image courtesy whitehouse.gov)

President Woodrow Wilson tried to keep the U.S. out of the killing fields in Europe. (Image courtesy whitehouse.gov)

Although Oregonians expressed diverse opinions, they generally followed the political mood of the nation. Isolationist or strict neutrality arguments held sway in national political debate during the early period of World War I. But these arguments would be weakened by cultural, economic, and military factors.

Isolationism Versus Imperialism

By the time of World War I, the U.S. had risen to become arguably the most powerful nation in the world. Many progressives believed much of its power derived from its ability to avoid costly entanglements in Europe and elsewhere. America, they argued, could serve the world best by concentrating on reforms at home and setting an example of peace and democracy.

But a countervailing opinion promoted the expansion of American power and influence to other continents. Many watched enviously as several European nations divided up Africa and other regions at an accelerating rate beginning in the 1880s. Certainly,

the U.S. had flexed its muscles, particularly during the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt. But the nation mainly focused on economic expansion through efforts such as the building of the Panama Canal. Many people decried the fact that a democratic America held onto the Philippines long after taking it during the Spanish-American War. Critics claimed this "imperialism" was inconsistent with the founding principles of the United States.

Cultural and Economic Complications

While President Woodrow Wilson called on Americans to be "neutral in fact as well as in name" at the beginning of the war, most people couldn't help but identify with one side or the other. Millions of Americans were of German descent. Many others traced their heritage as Czechs, Slovaks, and related ethnic groups to Germany's Central Power ally Austria-Hungary. Most of the sizable population of Irish-Americans sympathized with the Central Powers, reasoning that an enemy of the hated British oppressors of Ireland would be a friend of theirs. Conversely, the nation as a whole carried widespread sympathy for the western Allies. The large population of British Americans played a part. But more important was the commonality of language and institutions with Britain. Certainly, President Wilson was known to admire British culture. But in spite of these sympathies, most Americans opposed entry into the war.

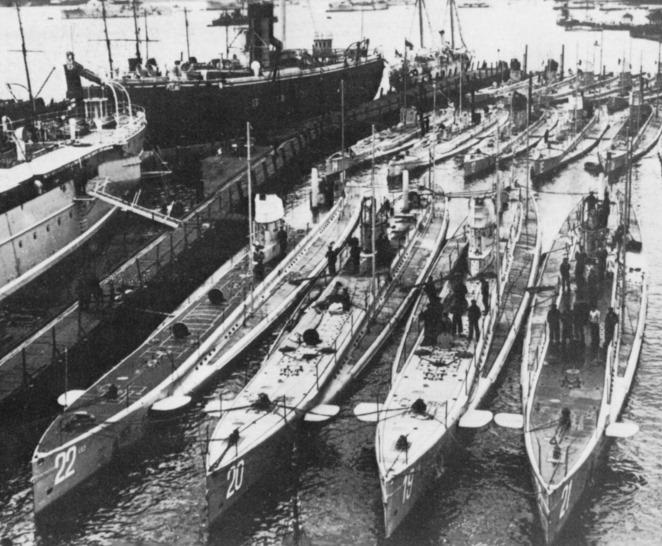

Unrestricted submarine warfare by the German U-boats, like these shown in a German harbor, finally proved to be a key reason for the American entry into the war on the side of the Allies. (Image courtesy uboat.net)

Unrestricted submarine warfare by the German U-boats, like these shown in a German harbor, finally proved to be a key reason for the American entry into the war on the side of the Allies. (Image courtesy uboat.net)

The American economy boomed during the period of neutrality. The war created a tremendous demand for American industrial and agricultural products. Both sides placed orders with U.S. companies but British blockades of German ports and their confiscation of cargoes limited the amount that reached Germany. Wilson protested what he considered to be British interference with the right of a neutral nation to trade with either side.

Nevertheless, by 1915, while still officially neutral, the U.S. began to provide cash-strapped Britain and France with enormous loans to pay for the materials they ordered. This made American industrialists and financiers rich but it also further compromised "the true spirit of neutrality." Consequently, the United States had a strong economic interest in preventing a German victory.

Strict Neutrality Collapses

This economic help to the Allies was accompanied by what were seen as German assaults on American neutrality. In 1915, a German submarine sank the British passenger liner Lusitania, resulting in 128 American deaths. America was outraged. Other incidents involving attacks on Americans also inflamed sentiment against Germany over time.

President Wilson's complicated diplomatic and economic dance of neutrality continued into 1916. On the eve of the American entry into World War I, philosophical arguments for avoiding outside entanglements were overlaid with the grisly reality of three years of trench warfare in Europe. After running for reelection in 1916 under the banner "He kept us out of war," a series of German provocations finally led Wilson to ask Congress for a declaration of war in April 1917. Chief among the American grievances was the earlier German resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare, which now targeted the merchant ships of neutral countries such as the United States. These ruthless naval attacks combined with German diplomatic intrigue in Mexico to make war inevitable.